Children of the Mist’

The MacGregors - Highland Outlaws

In 1558 a deadly feud took place between Clan MacLaren and Clan Gregor, when the MacGregors were

accused of killing 18 MacLaren men – as well as their families - and of then taking possession of their farms.

This incident was not investigated until 1604 when the MacGregors were on trial for slaughtering many men

of Clan Colquhoun.

In 1589, Lord Patrick Drummond, of Clan Drummond, appointed his deputy kinsmen, John Drummond of

Drummond-Ernoch to be the Royal Forester of Glen Artney. It was in this post that John Drummond cut

off the ears of some MacGregors he had caught poaching. In revenge, the MacGregors attacked Drummond

and cut off his head. The MacGregors then proceeded to the house of John’s sister, burst in, and demanded

bread and cheese. The MacGregors then unwrapped John’s head and crammed its mouth full.

What’s more, killing a Royal Forrester was an offence against the British Crown – and the Crown promptly

issued letters of ‘fire and sword’ against the clan, making it illegal to shelter or have any dealings with clan

members. The dispossessed MacGregors rustled cattle and poached deer to survive. Various ‘fire and

sword’ orders were continually proclaimed against the MacGregors for the better part of 200 years - they

simply couldn’t keep out of trouble.

With regard to the murder of the Royal Forester, in 1590 the MacGregor chief was held personally responsible - even though the chief was not involved in the killings. However, he was pardoned by King James VI in 1596.

But in 1602 two MacGregors were refused hospitality by Sir Alex Colquhoun at Luss, on the banks of Loch Lomond. This may have been related to an incident in 1592 when the MacGregors fired an arrow which killed Sir Humphrey Colquhoun. But the insult of being refused hospitality had to be revenged - and the MacGregors attacked Rossdhu Castle, killed two men and removed a few hundred cows and other livestock. The Colquhoun chief took the matter to the King (with a suitably embellished story).

The Battle of Glen Fruin took place in 1603 where the MacGregors were victorious, defeating five hundred Clan Colquhoun men, of which three hundred of Colquhouns were on horseback. This combined force of Colquhoun foot and horse were defeated by four hundred MacGregor men. Over two hundred of the Colquhoun men were killed when the MacGregors, who had split into two parties, attacked from front and rear and forced the horsemen onto the soft ground of the Moss of Auchingaich. It wasn’t until the 1700s that the hatred between these clans was laid to rest when, at Glen Fruin on the site of the massacre, the chiefs of the Clans Gregor and Colquhoun met and shook hands.

The matter at Glen Fruin was reported to the Privy Council in Edinburgh, and in April 1603, an Act of Parliament was passed proscribing the very name MacGregor. The MacGregors were formally banished by Scotland’s King James VI who issued an edict proclaiming the name of MacGregor ‘altogidder abolisheed’, meaning that those who bore the name must renounce it or suffer death. This meant any member of Clan Gregor (if caught) could be beaten, robbed or killed without fear of punishment. Anyone with the name MacGregor was banned from the church (no marriages, burials, communion, etc.). It was complete ostracism for the entire clan.

Alistair MacGregor of Glen Strae was captured, having sought protection from the Chief of the Campbells* to go to London to beg clemency from Scotland’s King James VI, who had recently claimed the throne as James I of England. The Campbells gave Alistair safe passage to the borders, but arranged in advance for British soldiers to capture him on the English side of the border. He was then returned to Edinburgh to stand trial. In 1604, along with eleven of his chieftains, Alistair was hanged at Edinburgh’s Mercat Cross (or it may have occurred in the Edinburgh Tollbooth, the site of which is now marked by the Heart of Midlothian). He was hung one notch higher than his relatives, to distinguish his rank.

This treachery united the entire highlands in their loathing of the Campbells.

Clan Gregor was scattered, many taking other names, such as Murray, King, or Grant. They were hunted like animals, flushed out of the heather by bloodhounds.

* MacGregors have quite a ‘history’ with the Campbells …

The MacGregors suffered a reversal of fortune when the Scottish king,Robert the Bruce, granted the barony of Loch Awe, which included much of the MacGregor lands, to the chief of Clan Campbell. The Campbells ejected the unfortunate MacGregors from these lands, forcing them to retire deeper into their lands until they were largely restricted to Glenstrae. The MacGregors fought the Campbells for decades and were eventually dispossessed of their lands. Reduced to the status of outlaws, they rustled cattle and poached deer to survive.

The taking of Castle Grant in the 1300s; Originally a Clan Comyn stronghold,Clan Grant traditions tell us that the castle was taken from the Comyns by a combined force of the Grants and MacGregors. The Clan Grant and Clan Gregor stormed the castle and in the process slew the Comyn Chief - and kept the Chief's skull as a trophy of this victory. The skull of the Comyn was taken as a macabre trophy and was kept in Castle Grant and became an heirloom of the Clan Grant. (In the late Lord Strathspey's book on the Clan, he mentions that the top of the cranium was hinged, and that he saw documents kept in it.) Clan tradition predicts grave things if the skull ever leaves the hands of the family - prophesying that the Clan would lose its lands in Strathspey.

Iain of Glenstrae died in 1519 with no direct heirs. This plunged the Clan Gregor into disarray as the powerful Campbells meddled with succession and asserted claim to the last remaining MacGregor lands. In 1560, the Campbells dispossessed Gregor Roy MacGregor, who waged war against the Campbells for ten years before being captured and killed. His son, Alistair, claimed the MacGregor chiefship but was utterly unable to stem the tide of persecution which was to be fate of the "Children of the Mist."

Argyle and his Clan Campbell henchmen were given the task of hunting down the MacGregors. About sixty of the clan made a brave stand at Bentoik against a party of two-hundred chosen men belonging to the Clan Clan Cameron, Clan MacNab, and Clan Ronald, under command of Robert Campbell, son of the Laird of Glen Orchy. In this battle, Duncan Aberach, one of the Chieftains of the Clan Gregor, his son Duncan, and seven other MacGregors were killed. But although they made a brave resistance, and killed many of their pursuers, the MacGregors, after many skirmishes and great losses, were at last overcome.

Inspite of living as outlaws, in 1606 the Clan Gregor was able to gather for the Battle of Cairnwell. A force of around 200 men from the Clan Gregor, and some Catarans, made off with around 2,700 of the MacThomases cattle. The MacThomases eventually caught up with their enemies, the MacGregors, and defeated them - but not before the MacGregors had butchered most of the MacThomases cattle, just out of pure spite!!! This caused much financial damage to the MacThomases with some of the clansmen being completely ruined.

An Act of the Scottish Parliament from 1617 stated (translated into modern English):

In 1653, the Earl of Glencairn travelled through Rannoch looking for support for England’s King Charles II – the Stuart King who was exiled in Europe after being defeated by Cromwell and the English Parliament in 1651.

The Clan Gregor raised their fighting men from the Isle of Rannoch and joined forces with the Earl of Glencairn. (Glencairn had no difficulty recruiting the MacGregors - as one of King Charles’ opponents was the Earl of Argyll, a Campbell, and therefore a hereditary enemy of Clan Gregor.)

Alexander, the 12th chief of the Clan Robertson also raised his clan in rebellion and joined forces with Glencairn – leading his men from Fea Corrie.

The MacGregors and the Robertsons met above Annat and marched up the old path to Loch Garry. History informs us that the leaders quarrelled so much amongst themselves that General George Monck, an English Parliamentarian, had little difficulty in winning the ensuing Battle of Dalnaspidal.

In 1719, during the early Jacobite Uprisings, men from the Clan Gregor fought at the Battle of Glen Shiel, led by Rob Roy (who was wounded).

Ireland’s ‘Republican Amnesia’ on the Mend?

the Irish National War Memorial at Islandbridge in Dublin commemorates the 50,000 Irishmen - all volunteers - who

died, and the 300,000 who fought in the British Army during the 1914-1918 First World War

Symbol of Remembrance in Memory of a Nation’s Sacrifice

Although small commemorations took place for a few years after the 1939-1945 Second World War, the ‘political

situation’ (lingering anti-British feeling) in Ireland did not sanction that the 1914-1918 Irish National War Memorial

Gardens be ‘officially’ opened and dedicated. Subsequent lack of staff and resources being allocated by successive

Irish governments also allowed the site to fall into neglect, decay and dilapidation. During the 1970s and early

1980s it had become an open site for caravans and animals of the Irish ‘Tinker’ community (gipsies).

Sixty years of shameful official neglect had left its mark.

From the mid-1980s, restoration works to renew the park and gardens to their original splendour were undertaken by the Office of Public Works, co-funded by the National War Memorial Committee which is representative of Ireland, both north and south.

On the 10th of September 1988 the Gardens were formally dedicated by representatives of the four main Churches in Ireland … and unofficially opened to the public.

The first real, fully official ‘opening and dedication’ took place with a State commemoration to mark the 90th anniversary of the Battle of the Somme on the 1st of July 2006. This commemoration was attended by the President of Ireland, Mary McAleese, the Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Bertie Ahern, Members of the Oireachtas (the two houses of the Irish parliament), the Diplomatic Corps of the Allies of the First World War, delegates from Northern Ireland, representatives of the four main Churches, and solemnly accompanied by a Guard of Honour and Band from the Irish Army.

The Gardens were designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and are characteristic of his style of simple dignity. Unlike his other war memorials, Lutyens designed a tranquil garden on the banks of the River Liffey - a garden that was originally intended to be linked to the Phoenix Park on the other side by a bridge. This three arched bridge was to be built on the central axis of the main lawn. The elaborate layout includes a central Sunken Rose Garden composed by a committee of eminent horticulturalists, various terraces, pergolas, lawns and avenues lined with impressive parkland tress, and two pairs of Book Rooms in granite representing the four provinces of Ireland.

The sunken Garden of Remembrance surrounds a 1914-1918 ‘War Stone’ of Irish granite symbolising an altar, which weights seven and a half tons. The dimensions of this are identical to many other First World War memorials, found throughout the world, and is aligned with the Great Cross of Sacrifice and the Central Avenue.

The Book Rooms take the form of small limestone pavilions with sloping stone roofs and blank niches. Originally these rooms contained books designed by Harry Clarke containing all the names of the war dead.

In the granite paved pergolas surrounding the Garden are illuminated Volumes recording the names of all the 1914-1918 Irish war dead, and these were once publicly accessible, although the threat of ‘republican’ vandalism has now had these Book Rooms closed except for visits by appointment. The park ranger now has a facility in one of the pavilions to view and print any page from the 12 book memorial record.

The ‘Ginchy Cross’ - a wooden cross fashioned on the style of a Celtic Cross - is also kept in the same pavilion. This wooden cross had been designed on a sheet of blotting paper, by Major General W.B. Hickie, the commander of the 16th Irish Division, and was made from old oak beams by the divisional pioneer troops. It was originally erected during the war on the Somme in a field between the villages of Guillemont and Ginchy. Those two villages had been liberated by the 16th Irish at the cost of 240 officers and 4,090 men killed, wounded or missing. Granite replicas of the original cross were erected in 1926 at Guillemont and at Wytscheate in Belgium, while a third was erected in Salonica, in Macedonia, to commemorate the officers and men of the 10th Irish Division who fought in Gallipoli, Macedonia and the Middle East. The 36th Ulster Division also has a splendid memorial in France.

The Irish National War Memorial gardens occupy an area of about eight hectares on the southern banks of the River Liffey, almost opposite the Magazine Fort and obelisk in the Phoenix Park, and about three kilometres from the centre of Dublin - on grounds which gradually slope upwards towards Kilmainham Hill. (Old chronicles describe Kilmainham Hill as the camping place of Brian Boru and his army prior to the last decisive Battle of Clontarf on the 23rd of April 1014.)

The Memorial was probably the last to be erected to the memory of those who sacrificed their lives in the 1914-1918 ‘Great War’, and is one of the finest - if not the finest - in the world.

Marshal Foch’s Tribute to the Irish Soldiers who died in the First World War

PARIS, FRIDAY, Nov. 9th, 1928 …

“There is no better tribute to Irish valour than that paid after the armistice by one of the German High Command, whom I had known in happier days. I asked him if he could tell me when he had first noted the declining moral of his own troops, and he replied that it was after the picked troops under his command had had repeated experience of meeting the dauntless Irish troops who opposed them in the last great push that was expected to separate the British and French armies, and give the enemy their long-sought victory.

“The Irishmen had endured such constant attacks that it was thought that they must be

utterly demoralised, but always they seemed to find new energy with which to attack their assailants, and in the end the flower of the German Army withered and faded away as an effective force.”

Marshal Foch continued … “The heroic dead of Ireland have every right to the homage of the living for they proved in some of the heaviest fighting of the world war that the unconquerable spirit of the Irish race— the spirit that has placed them among the world’s greatest soldiers—still lives and is stronger than ever it was.

“I had occasions to put to the test the valour of the Irishmen serving in France, and, whether they were Irishmen from the North or the South, or from one party or another, they did not fail me.

“Some of the hardest fighting in the terrible days that followed the last offensive of the Germans fell to the Irishmen, and some of their splendid regiments had to endure ordeals that might justly have taxed to breaking-point the capacity of the finest troops in the world.

“Never once did the Irish fail me in those terrible days. On the Somme, in 1916, I saw the heroism of the Irishmen of the North and South, I arrived on the scene shortly after the death of that very gallant Irish gentleman, Major William Redmond. I saw Irishmen of the North and the South forget their age-long differences, and fight side by side, giving their lives freely for the common cause. In war there are times when the necessity for yielding up one’s life is the most urgent duty of the moment, and there were many such moments in our long drawn- out struggle. Those Irish heroes gave their lives freely, and, in honouring then I hope we shall not allow our grief to let us forgot our pride in the glorious heroism of these men. “They have left to those who come after a glorious heritage and an inspiration to duty that will live long after their names are forgotten. “France will never forget her debt to the heroic Irish dead, and in the hearts of the French people to-day their memory lives as that of the memory of the heroes of old, preserved in the tales that the old people tell to their children and their children’s children.”

British submarine heritage is Irish?

John Philip Holland was one of four brothers who were born in Liscannor, County Claire, Ireland to an Irish gaelic-speaking mother mother, Máire Ní Scannláin, and John Holland, and learned English properly only when he attended the local English-speaking Irish National School system and, from 1858, in the Christian Brothers in Ennistymon. Holland joined the Irish Christian Brothers in Limerick, and taught in Limerick and many other centres in the country. Due to ill health, he left the Christian Brothers in 1873.

He and his brother, Mícheál, were both active in the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), the precursor to the Irish Republican Army (IRA). Mícheál introduced the inventor to the revolutionary group. Holland and the Fenians conceived a plan to develop a small submarine that could be sealifted on a large merchant ship to an area near an unsuspecting British warship. The submarine would then be released from the bottom of the merchant vessel and attack the warship.

Holland emigrated to the USA in 1873. Initially working for an engineering firm, he returned to teaching again for a further six years in St. John’s Catholic School in Paterson, New Jersey. In 1875, his first submarine designs were submitted for consideration by the U.S. Navy, but turned down as unworkable. The Fenians, however, continued to fund Holland's research and development expenses at a level that allowed him to resign from his teaching post. In 1881, the Fenian Ram was launched, but soon after, Holland and the Fenians parted company angrily, primarily due to issues of payment within the Fenian organization, and between the Fenians and Holland. The submarine is now preserved at Paterson Museum, New Jersey.

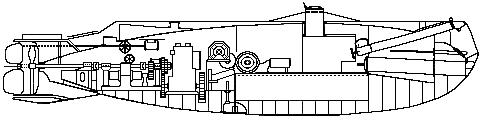

Holland continued to improve his designs and worked on several experimental boats, prior to his successful efforts with a privately built type, launched on 17 May 1897. This was the first submarine having power to run submerged for any considerable distance, and the first to combine electric motors for submerged travel and gasoline engines for use on the surface. She was purchased by the Navy (on 11 April, 1900) after rigorous tests and was commissioned on 12 October, 1900 as USS Holland. Six more of her type were ordered and built under the supervision of Arthur Leopold Busch, the head of construction at the Crescent Shipyard in Elizabeth, New Jersey and the same shipyard (and man) where the USS Holland (SS-1) was developed. The company that emerged from under these developments was called The Electric Boat Company, founded on 7 February, 1899.

The USS Holland design was also adopted by others, including the Royal Navy in developing the Holland Class Submarine. The Imperial Japanese Navy employed a modified version of the basic design for their first five submarines, although these submarines were at least 10 feet longer at about 63 feet.

The Noble Society of Celts, is an hereditary society of persons with Celtic roots and

interests, who are of noble title and gentle birth, and who

have come together in a search for, and celebration of, things Celtic.

"Summer Edition 2009"

Submarine Fenian Ram

You can visit the Submarine Fenian Ram and John Holland's first submarine at the Paterson Museum in Paterson, NJ. The Fenian Ram is the first practical submarine, in that it was able to run on its own power using its 2 cylinder Brayton oil engine and dive and submerge successfully. This sub was actually commissioned by the Irish Fenian Brotherhood, an anti-British Irish group that wanted to use it to sink British shipping in an effort to get the Brits out of Ireland.

Holland actually got the sub to the point were it would run at about 9 knots surfaced. Submerged the sub had a limited running capability as it ran on the air from the crew's compartment. Once submerged the hull was pressurized to the same level as the surrounding water. If they did not do this the back pressure from the water outside the hull would prevent the Brayton engine from starting and running. As you could imagine this was not the most practical solution and John Holland planned to install a dedicated compressed air reservoir to feed air to the engine while running submerged.

The Fenian Ram's weapon was a pneumatic gun, shooting a projectile out of the bow. Initially there were serious problems with the gun as the projectile would take a sharp turn upwards and leap out of the water. John Holland solved this by drilling a hole near the muzzle of the barrel that would allow the charge of compressed air behind the projectile to vent through the hole preventing the column of air from kicking the bottom of the projectile down and shooting it up. ]

The Battle of Glen Shiel 1719, by Peter Tillemans

Tillemans shows the battle from the government position and is based on eye-witness accounts and contemporary plans for the deployment of forces. The figure mounted on the rearing dark horse is probably General Joseph Wightman, commander of the government garrison at Inverness.

The Jacobite Rising of 1719 was another failed attempt to restore the Stuart dynasty to the British throne. On the evening of the 10th of June the mostly Catholic Scots attacked the Protestant English-Hanoverian forces on the slopes of Glen Shiel (where the current A87 highway runs between Loch Cluanie and Loch Duich).

During the 1745 - 1746 uprising Clan Gregor, who served under the Duke of Perth, fought as Jacobites at the Battle of Prestonpans (1745) and the Battle of Culloden (1746). However, a large section of the MacGregor fighting men missed the battle at Culloden; as they were with their Chief, Gregor Ghlun Dubh (Black Knee) in Sutherlandshire tracking the English and Hanoverian troops there.

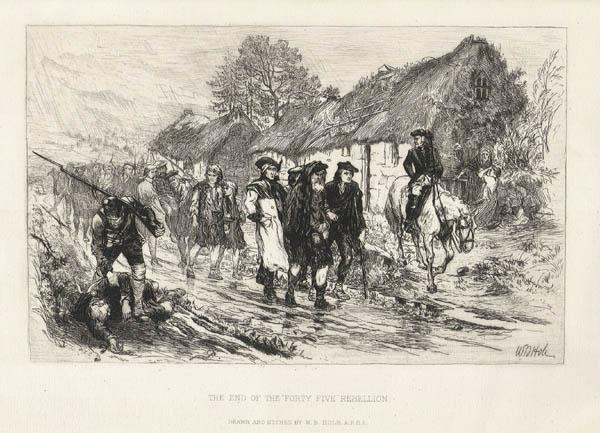

The End of the 'Forty Five' Rebellion defeated Jacobites retreating

Though reduced to the status of outlaws, the MacGregors never forgot or relinquished their identity. They fought for the Scottish king (who had renewed the Acts against them), under the command of Montrose in 1644-45 (the Campbells had fought on the side of Cromwell and the English Parliament).

In 1661, these Acts were repealed, but only for about 30 years, until Protestant William of Orange and his successors renewed them and kept them in force.

No wonder that Clan Gregor fully supported the Jacobite risings in 1715 and 1745.

Persecution of the MacGregors continued until 1774, when The Acts were finally repealed permanently - Clan Gregor having survived almost 200 years as outlaws.

The most famous, or infamous member of the clan was Robert MacGregor, who acquired the name of ‘Roy’ early in life due to his mop of red curly hair. Rob Roy was a multi-talented man - a great swordsman and soldier (fighting alongside his father by the age of 18 against Protestant King William of Orange), an astute businessman, and master of the highland ‘protection racket’.

He was born in February 1671 at Glengyle at the head of Loch Katrine in the Trossachs, and was the third son of clan chief Lieutenant-Colonel Donald Glas MacGregor of Glengyle. His mother Mary was a Campbell, and it was from her that he inherited his red hair, leading to his nickname, Rob ‘Ruadh’ (Gaelic for ‘red’) which was later anglicised into ‘Rob Roy’.

As the son of a senior member of the clan, he was well educated, not just in reading and writing but in the crafts of fighting and swordsmanship. While Gaelic was his native tongue, he spoke (and wrote) in English also.

Rob Roy, who used his mother’s name of Campbell (the MacGregor name had been proscribed since 1603 in reprisal for the clan’s part in a bloody battle at Glen Fruin), moved on to set up a business driving Highland cattle to market in Crieff.

His early days were spent peacefully as a drover, buying and selling Highland cattle, under the patronage of the Duke of Montrose. As a cattle dealer, Rob was making plenty of money buying stock in Scotland and selling them at a profit after taking them to England.

In January 1693 he married his cousin Mary Helen MacGregor of Comar and they subsequently had four sons: James Mor, Ranald, Coll, and Robin Oig who himself went on to achieve literary distinction in a cameo role in Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel ‘Kidnapped’.

Rob obtained land on the east side of Loch Lomond near Inversnaid but augmented his meagre living there with both cattle rustling and cattle droving. Cattle owners who paid ‘black rent’ or ‘black meal’ (the origin of the word blackmail) would have their cattle protected by Rob and his fellow MacGregors. Since they were often the cattle rustlers, paying to have them protect your cattle could be beneficial!

The mostly Catholic MacGregors continued to support the deposed Catholic King James VII of Scotland (also known as James II of England) against the Protestant Dutchman, William of Orange, and Queen Mary. So, when John Graham of Claverhouse, Viscount Dundee (also known as ‘Bonnie Dundee’) raised an army in support of King James (and his Jacobite cause), the MacGregors immediately rose in rebellion and joined him.

Rob Roy and his father fought at the Battle of Killiecrankie on the 27th of July 1689 which the Jacobites won, despite the death of their leader. And although both sides lost many men, Rob and his father, Donald Glas, survived.

During the following winter, however, Donald Glas was captured on a cattle raid and imprisoned.

To eke out their poor income, the MacGregors formed the ‘Lennox Watch’ to protect cattle and on one occasion Rob restored cattle which had been stolen (by the MacRaes) to their rightful owner, the Campbell Earl of Breadalbane. This raised Rob’s status and he was called on to protect a number of other estates.

With the Jacobite cause getting nowhere, the British Secretary of State agreed in 1691 that there would be an armistice - if the clan chiefs agreed to sign an Oath of Allegiance. (It was the late signing of this Oath that led to the massacre of the MacIans, a sept of the clan Donald, in Glen Coe in the following year).

Initially, Donald Glas refused to sign - but did so after the death of his wife. But after signing, the Privy Council demanded that he pay the cost of his imprisonment. To help pay the money, Rob undertook a raid to steal some cattle from around the Lowland village of Kippen. The men from there resisted and one was killed in the ensuing fight.

During a visit to Glasgow in December 1695, Rob was arrested for an earlier misdemeanour and was sentenced to be sent to the army in Flanders. But he escaped and returned home. Despite hard times, he managed to prosper and at least five of his sons survived to manhood. During this time his reputation as a swordsman was enhanced by winning a number of duels - his long arms were said to give him an advantage.

Late in 1711 Rob Roy borrowed £1,000 from the Duke of Montrose, a landowner based at Mugdock Castle near Milngavie to north of Glasgow, to purchase cattle for the following year’s market. But in early 1712 Rob Roy’s head drover, having purchased the cattle, then sold on the herd and disappeared with the funds. Rob Roy returned from an unsuccessful search for the drover to find he had been bankrupted and outlawed by the Duke of Montrose. Montrose took his revenge by seizing MacGregor’s house and throwing his wife and four young sons out into the depths of winter – there was also talk that Montrose’s soldiers raped and branded Rob’s wife.

Rob Roy sought revenge on the Duke of Montrose through a sustained campaign of cattle-rustling, theft and banditry. This included kidnapping Montrose’s factor (estate business manager), complete with over £3,000 of rent money that he was carrying at the time. Gradually the targets for Rob Roy’s banditry grew to include other landowners who were not prepared to pay him to ‘protect’ their stock and property. Meanwhile, his vendetta against the Duke of Montrose gained him a powerful ally in the Duke of Argyll, who was a long-standing enemy of Montrose. The Duke of Argyll gave Rob refuge in Glen Shira, not far from Inverary.

Following his annus horribilis of 1712, Rob Roy was accused of fraudulent bankruptcy, and in 1715 he raised the MacGregors in rebellion at Aberdeenshire, and he also acted as guide to the Jacobite army as it marched from Perth towards Stirling in November. This culminated in the Battle of Sheriffmuir which, marginally, the Jacobites won. But hesitation on the part of the Jacobite leaders and the late arrival of James VIII from France led to the withering of the Uprising.

Nonetheless, the much smaller Government army under the Duke of Argyll did just managed to prevent the Jacobites from reaching the Lowlands. Rob Roy was then found trailing in the wake of the Jacobite rebel army at Sheriffmuir, waiting patiently for any booty that he could lay his hands on. His loyalties were split between his Jacobite upbringing and loyalty to Catholic King James, and his alliance with the Protestant Duke of Argyll - and he seems to have been an onlooker at the battle itself, though claims he was secretly working for the Duke of Argyll have never been proved.

Nonetheless, for his part in the uprising Rob Roy emerged with a price on his head for treason, in addition to the earlier charges of banditry. Rob Roy eventually gave up some rusty weapons to the Duke of Argyll - who gave him a house in Glen Shira, where, for safety, Rob set up home, as it was close to the Duke of Argyll’s base in Inveraray - and he then went on to play a minor role in the 1719 Jacobite uprising culminating in the defeat of the Jacobites and Spanish troops at the Battle of Glen Shiel.

In 1720 Rob Roy moved back near Balquhidder (both Montrose and Atholl had given up trying to capture him by this time) and resumed his previous life.

In 1723, Daniel Defoe (author of Robinson Crusoe) was in Scotland as an English Government spy - and he wrote an embellished account of Rob’s adventures entitled ‘Highland Rogue’. This, like the later novel by Sir Walter Scott, helped to enhance his reputation.

Rob Roy continued to raid the lands of the Duke of Montrose, who tried on many occasions to capture this thorn in his side. Montrose obtained letters of ‘Fire and Sword’ against Rob Roy McGregor. Montrose did manage to capture Rob Roy at Balquhidder but, on the journey back to Stirling, Rob escaped. Then the Duke of Atholl tricked Rob, breaking a promise of safe conduct in the process. Rob was captured, but while in prison in Dunkeld he bribed the guards and escaped yet again.

Captured yet again, and on the point of being transported to Barbados for life as a plantation slave in 1727, Rob Roy received a Royal pardon by public acclaim and decided, as he was not getting any younger (he was now in his mid-fifties), that it was time to settle down. This he did and lived the rest of his life as a peaceful, law-abiding citizen …well, apart from the odd duel or two.

The same cannot be said about his violent sons, James and Rob Oig (Robert the Younger), but that is another story!

The last ten years of Rob’s life were relatively peaceful. In 1730 he was converted to Catholicism - he had not been a particularly enthusiastic Protestant and his belief in the Jacobite cause may have influenced his decision. Rob died on 28 December 1734 after a short illness. He died as a piper was playing ‘I shall return no more’ for a departing visitor.

During the mid to late 1800s, people all over the world were enthralled by the novels of Sir Walter Scott, who portrayed a man called ‘Rob Roy’ in his stories …a dashing and chivalrous outlaw.

The truth however was a little less glamorous of course …

For centuries the ‘Wild MacGregors’, cattle rustlers and brigands to a man, were the plague of the Trossachs in Scotland. The Wild MacGregors earned their name and living through ‘cattle lifting’, and extracting money from people, in exchange for offering them protection from thieves.

In the early eighteenth-century, Rob Roy Macgregor had established a flourishing protection racket, charging farmers an average 5% of their annual rent …to ensure that their cattle remained safe.

He had complete control over the other raiders in Argyll, Stirling and Perth, and so could guarantee that any cattle stolen from his customers would be returned to them.

Those who did not pay regretted it …as he had them stripped of all they possessed.

Rob Roy was not the sort of man to argue with!

However Rob Roy’s story has continued to grow and grow since his death. Even after Sir Walter Scott’s 1818 novel, ‘Rob Roy’, he has been the subject of two Hollywood films during the 1900s. The Trossachs district in Scotland has become known as ‘Rob Roy Country’. The main Tourist Information Centre in Callander is called the ‘Rob Roy and Trossachs Visitor Centre’. And in 2002 a new unofficial long distance hiking trail called the ‘Rob Roy Way’ was set up to link together many places that featured in Rob’s life.

There is even a ‘Rob Roy’ cocktail !!!

… one jigger scotch whisky (1-1/2 oz.), 1/2 oz. vermouth (sweet or dry depending on your taste) and a dash of bitters (optional). Pour over rocks and stir, or use a shaker. Pop in a cherry or lemon twist.

Drink up !!!

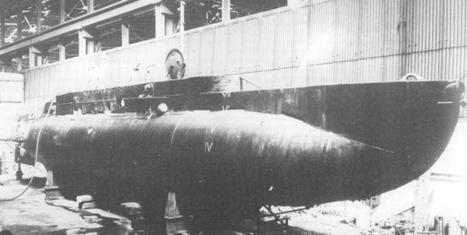

XE3 on the surface

James ‘Mick’ Magennis V.C

Midget Submarine Hero from Belfast’s Falls Road

‘Mick’ Magennis was the only man from Northern Ireland to be awarded a Victoria Cross in the Second World War – but it was not until after his death that he got the full civic honours that Belfast sectarian prejudice denied him in 1945.

In 1945 ‘Mick’, who was 25 at the time, earned the Victoria Cross for his remarkable courage as a navy frogman, clamping six limpet mines to the hull of a Japanese heavy cruiser, the Takao, which was guarding Singapore harbour. It blew apart five hours later. ‘Mick’ also saved his three colleagues onboard their midget submarine, the HMS XE3. Exhausted, and suffering from the cold, after attaching the mines because he had first to scrape barnacles from the hull, he then insisted on leaving the midget sub’ again to free it from the sea bed – despite a constant leak of oxygen from his breathing apparatus during both his dive ‘sorties’.

Although he was feted at Buckingham Palace, ‘Mick’ Magennis was never given the official recognition that was his due by the Unionist-dominated Belfast City Council. He was a Catholic, and Stormont, citadel of Unionist power, had been enraged by the award. Although the Northern Ireland public collected £3,600 in appreciation of his heroism, the council refused to give him the freedom of the city. However, amid the atmosphere of reconciliation that followed the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, this wrong was put right when a 6ft-high Portland stone and bronze memorial was unveiled in the City Hall grounds.

‘Mick’ was born on the 27th of October 1919 in Belfast, Ireland. He attended St Finian’s Catholic School in the Republican Catholic ‘Falls Road’ area of Belfast until the 3rd of June 1935, when he enlisted in the Royal Navy as a boy seaman.

‘Mick’ served on several different warships between 1935 and 1942, when he joined the submarine branch. Before joining the submarine branch, he served on a destroyer, HMS Kandahar, which was mined near Tripoli, off Libya, in December 1941. The destroyer was irreparably damaged and was scuttled the next day.

In December 1942, ‘Mick’ transferred into the submarine service and in March 1943 he volunteered for ‘special and Hazardous duties’ — which meant midget submarines (‘X-craft’).

‘Mick’ trained as a diver, and in September 1943 took part in the first major use of the X-craft during Operation Source – when two midget sub’s, HMS X7 and HMS X6, penetrated Kafjord in Norway and disabled the German battleship Tirpitz. For his part in the attack ‘Mick’ was decorated with an ‘M.I.D.’ (mentioned in dispatches) “for bravery and devotion to duty”.

By July 1945 ‘Mick’ was serving as the diver on the midget submarine HMS XE3 under the command of Lieutenant Ian Fraser, in the British Pacific Fleet.

By the middle of 1945, the Japanese were retreating all across South East Asia, but they still held on to the vital naval base at Singapore. The high command believed that an attack would induce the Japs to abandon it for the safer bases of their homeland. The codename for the operation was Operation Struggle.

The naval base at Singapore lies on the northern shore of Singapore island, several miles up the Johore Strait. A submarine could not have hoped to get through the long narrow channel undetected so it was decided that a midget submarine might have a better chance. The midget sub’ selected was XE3, commanded by Lt. Ian ‘Titch’ Fraser, RNR. The target was the 9,850-ton Japanese heavy cruiser Takao which was acting as a huge floating anti-aircraft battery in the defence of Singapore.

Another midget sub’, the XE1, had been tasked with attacking another Jap heavy cruiser at Singapore, the Myoko.

In addition to the big side charges, the XE type midget subs also carried an outfit of limpet mines, which had to be fixed to the target by a navy diver.

On the 30th of July 1945, XE3 was towed from Brunei to the vicinity of Singapore by British Submarine HMS Stygian, while XE1 was towed by HMS Spark.

XE3 slipped her tow at 23:00 hrs for the forty-mile journey up the Johore Straight. The XE3 deliberately left the mine-swept channel, and instead infiltrated through shallower waters at the side of the channel - through hazardous wrecks, minefields and listening posts. During their final approach to the target XE3 was nearly run down by a Jap cutter, but escaped detection. The journey took 11 hours but they reached Singapore harbour in safety and slipped past the Jap trawler guarding the boom gate. Two hours later they sighted the Jap heavy cruiser, lying close inshore and well camouflaged. For the last part of her run in, XE3 had to bump along the sea bed in very shallow water, in some places not more than 15 feet deep. She fell into a deeper hole and for eight minutes her propeller churned up mud until at last she managed to get out. Forty minutes later – 1300 hrs on the 31st of July – she arrived, hitting the Takao amidships in a heavy collision which, somehow, passed unnoticed on board the Jap heavy cruiser.

The Japanese heavy cruiser Takao

As XE3 came alongside she ran up against yet another difficulty. The water here was so shallow that the Takao was lying almost aground at her bow and stern. Amidships there was just sufficient depth for XE3 to force herself beneath the Jap’ heavy cruiser, but when she was under the Jap’s keel there was not enough room for the midget sub’s special diving hatch to be fully opened.

XE3's diver, ‘Mick’ Magennis, managed to squeeze himself out of the half-opened hatch to fix his limpet mines under the cruiser’s bottom. But they would not hold up in their proper position because of the heavy growth of weed and barnacles on the Jap’s hull. ‘Mick’ had to chip away at the heavy cruiser’s bottom to make a clean enough patch and even then he had to lash the limpets together in pairs with line passing under the Takao's keel. This was exceptionally tiring and ‘Mick’ had an extra handicap because of an escape of oxygen from his diving gear which ascended to the surface in a stream of bubbles. A less determined man would have been content to place a few limpets and then return to his midget sub, but ‘Mick’ was made of sterner stuff. He continued his work

until he had placed all of his mines along the cruiser’s bottom. The task took him three-quarters of an hour and he was completely exhausted by the time he made his way back to XE3.

With the limpets in position, Lieutenant Fraser released the big side charge under the Jap cruiser’s bottom and managed to work XE3 clear.

Shortly after withdrawing, Fraser attempted to jettison the limpet carriers, but one of them jammed on the hull of XE3 and would not release, and upset the buoyancy and trim of the boat.

‘Mick’ immediately volunteered to free it commenting: “I'll be all right as soon as I've got my wind, Sir.” This he did, after seven minutes of nerve-racking work with a heavy spanner. On completion ‘Mick’ returned to safely through the diving hatch for the second time, allowing the four-man midget sub’ to make its escape down the Johore Strait safely past all the dangers and out into the open sea, to meet the waiting British submarine Stygian for a tow back to base.

The Takao never sailed again.

‘Mick’s Victoria Cross citation was published in a supplement to the London Gazette of the 9th of November 1945:

ADMIRALTY

Whitehall, 13th November, 1945.

The King has been graciously pleased to approve the award of the VICTORIA CROSS for valour to: —

Temporary Acting Leading Seaman James Joseph MAGENNIS, D/JX. 144907.

Leading Seaman Magennis served as Diver in His Majesty’s Midget Submarine XE-3 for her attack on 31st July, 1945, on a Japanese cruiser of the Atago class. Owing to the fact that XE-3 was tightly jammed under the target the diver’s hatch could not be fully opened, and Magennis had to squeeze himself through the narrow space available.

He experienced great difficulty in placing his limpets on the bottom of the cruiser owing both to the foul state of the bottom and to the pronounced slope upon which the limpets would not hold. Before a limpet could be placed therefore Magennis had thoroughly to scrape the area clear of barnacles, and in order to secure the limpets he had to tie them in pairs by a line passing under the cruiser keel. This was very tiring work for a diver, and he was moreover handicapped by a steady leakage of oxygen which was ascending in bubbles to the surface. A lesser man would have been content to place a few limpets and then to return to the craft. Magennis, however, persisted until he had placed his full outfit before returning to the craft in an exhausted condition. Shortly after withdrawing Lieutenant Fraser endeavoured to jettison his limpet carriers, but one of these would not release itself and fall clear of the craft. Despite his exhaustion, his oxygen leak and the fact that there was every probability of -his being sighted, Magennis at once volunteered to leave the craft and free the carrier rather than allow a less experienced diver to undertake the job. After seven minutes of nerve-racking work he succeeded in releasing the carrier. Magennis displayed very great courage and devotion to duty and complete disregard for his own safety.

Lieutenant Fraser was also awarded the VC for his part in the attack.

Sub-Lieutenant William James Lanyon Smith (a reserve officer of the Royal New Zealand Navy), who was at the controls of XE3 during the attack, received the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC)

Petty Officer Third Class Charles Alfred Reed, who was at the wheel, received the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal (CGM).

Crew of midget submarine HMS XE3:

Leading Seaman J. ‘Mick’ Magennis V.C.; Lt Ian ‘Tich’ Fraser V.C. D.S.C.;

Lt. B. Carey D.S.C.; and Petty Officer Maughan C.G.M.

Today, ‘Mick’ Magennis has had several memorials erected in his honour. When Magennis first won the VC, he was treated rather shabbily by the City of Belfast. The first memorial in Belfast was only erected in 1999 after a long campaign by his biographer George Fleming.

The memorial, a bronze and stone statue, was officially unveiled in Belfast on the 8th of October 1999. The ceremony was conducted in the grounds of Belfast City Hall in the presence of Magennis’s son Paul, by Lord Mayor of Belfast, Bob Stocker. Magennis's former commanding officer, Ian Fraser, was reported as saying: “…. he was a lovely man and a fine diver. I have never met a braver man. It was a privilege to know him and it's wonderful to see Belfast honour him at last.” A wall mural commemorating James Magennis on the 60th anniversary of VJ Day was unveiled on the 16th of September 2005 by Peter Robinson MP (from Ian Paisley’s Democratic Unionist Party), who represents the Ward of East Belfast, including Tullycarnet.

In 1986 at a memorial service in Bradford Cathedral (England), the Submarine Old Comrade Association (West Riding Branch) erected a memorial plaque on an inner wall within the Cathedral. The plaque made of Welsh slate was supplied by ex-submariner Tommy Topham MBE. Rear Admiral Place VC, CB, CVO, DSC unveiled the plaque. In attendance was Petty Officer Tommy ‘Nat’ Gould, another submariner Victoria Cross recipient from the Second World War.

In 1998 a memorial plaque was installed by the Castlereagh Borough Council on the wall of Magennis’s former home at 32 Carncaver Road, Castlereagh, East Belfast. A memorial blue plaque sponsored by Belfast City Council was installed on the outer wall of the Royal Naval Association building at Great Victoria Street, Belfast by the Ulster History Circle.

Irish Fighting Music

Killaloe is a very popular marching song in Irish Regiments. Killaloe was written around 1887 by a 41-year-old Irish composer named Robert Martin, for the London Musical ‘Miss Esmeralda’ and was sung by a Mr E. J. Lohnen. The original lyrics relate the sorry story of a French teacher attempting to make himself understood to a difficult class at the Irish National School at Killaloe – however the Irish school boys totally misunderstand his French, and as a consequence they beat him up.

The Killaloe song, with original melody in 2/4 time, was made well known in military circles by a cousin of the composer, Lt. Charles Martin, who served with the 88th Connaught Rangers (‘The Devil’s Own’) from 1888 until his death in 1893. He composed a new set of lyrics, in 6/8 time, celebrating his Regiment’s fame, and although no mention is made of the tune in the regimental history of the Connaught Rangers, there is an interesting explanation which may well account for the cheer or ‘rebel yell’ in the military version of Killaloe. In the First Battalion of the Connaught Rangers (the old 88th Regiment of Foot), a favourite marching tune was ‘Brian Boru’ – and this was played generally when the Battalion was marching through a town, or after a hot and heavy march, when the Battalion was feeling the strain and the Colonel wished to revive the spirits of his men. On such occasions, at a time generally given by the Sergeant-Major, all ranks would give a regular ‘Rebel Yell’, during which the band would make a pause, and then continue playing. The march became popular among the other Irish Regiments and various other sets of lyrics were devised, some none too complimentary in tone.

The first known recording of Killaloe was made by Richard Dimbleby when he was serving as a BBC war correspondent somewhere in Northern France during the disastrous 1939/1940 campaign, shortly before the Dunkirk evacuation – during an outside radio broadcast while reporting on British troops advancing towards the Germans. The “Famous Irish Regiment” Dimbleby reports playing the Irish War Pipes as they marched past is not actually named, but would have to have been either the Royal Irish Fusiliers or the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers.

Again in 1944, the BBC recorded the First Battalion of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers’ Pipes & Drums playing Killaloe, during the advance to Monte Cassino in the bloody Italian campaign; by then this famous tune had been adopted as the marching song of the elite 38th Irish Brigade of the British 8th Army.

All articles Submitted by Michael Doyle