The Noble Society of Celts, is an hereditary society of persons with Celtic roots and

interests, who are of noble title and gentle birth, and who

have come together in a search for, and celebration of, things Celtic.

"Summer Edition 2009"

Captain Gallagher

Harassing the English Oppressor in Ireland

The Irish highwaymen who lived during the later half of the 18th century are often regarded as a more commercialised version of the Irish ‘Rapparees’.

The ‘Rapparees’ were mainly dispossessed Irish landowners whose land was confiscated to make way for Protestant English settlers - Crown favourites and military adventurers. This forced dispossessed Irish landowners to take to the forests and hills with as many followers as they could muster and wreak vengeance on the ‘New English’. The ‘Rapparees’ pursued a campaign of guerrilla warfare against the English ‘Planters’ and the British Crown, and were particularly active from the collapse of the 1641 Irish Rebellion, and the subsequent Cromwellian invasion, to about the middle of the 1700’s.

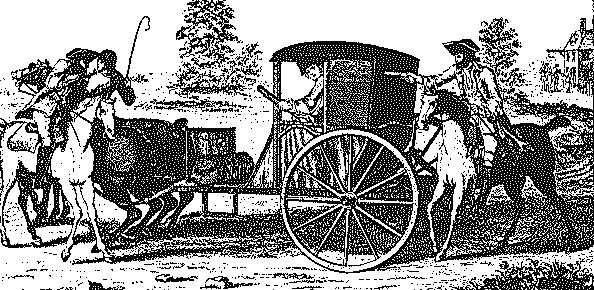

The Irish highwaymen who came after the ‘Rapparees’ were of a more proletarian origin and outlook - many of them had gained their knowledge of firearms through service with military or militia units. Some highwaymen carried out raids and hold-ups of mail coaches singly while other operated with a small band of followers – but rarely exceeding half a dozen. To the latter category belonged ‘Captain Gallagher’.

Born in Bonniconlon, County Mayo Captain Gallagher lived with his aunt in Derryronane, Swinford for much of his early life and was raised near the forest of Barnalyra.

The English officer dispatched messages to the Redcoats stationed in Ballina, Castlebar and Swinford for assistance. With a force of nearly 200 troops, the Redcoats then surrounded the house. Being ill and not wishing to endanger his host or his family, Captain Gallagher surrendered with out resistance.

Gallagher was rushed to Foxford and, after a hasty sham trial, was sentenced to be hanged. He was then taken to Castlebar for the sentence to be carried out.

Questioned before mounting the scaffold, Captain Gallagher asserted that all his treasure was hidden under a rock in Barnalyra. Hearing this, the English commanding officer hastily carried out the execution and then galloped towards the forest of Barnalyra, taking with him a hand-picked squad of English cavalry. Doubtless, visions of new-found wealth or rewards from the Crown helped to hurry them on. When the English reached Barnalyra they found to their dismay not the few rocks they had visioned but countless thousands of rocks of all shapes and sizes. After some days’ search, all they found was a jewel-hilted sword.

The puzzle about the location of Captain Gallagher’s treasure may never be solved. Some believe his confession was made in the hope he would be taken to Barnalyra to point out the rock in question. Gallagher knew his companions were hiding-out on the Derryronane-Curryane border close to the forest, and he may have had hopes of being rescued.

The spirit of Captain Gallagher lives on through the ages in the hearts of all those swashbuckling Irish gentlemen wandering the globe in pursuit of glory.

Michael Francis McCarthy

Knight Commander of the Holy Sepulchre

Aeternum vale

Michael McCarthy died suddenly on 3 August 2007 at his home in Sydney at the age of 57 years. Michael was an internationally renowned heraldic artist and expert on the heraldry of the Roman Catholic Church and an author of a number of texts on the subject including

Michael was a Vice-President of Heraldry Australia for a number of years. Many in the international community will recall meeting him at the 27th International Congress of Genealogical and Heraldic Sciences in St Andrews, Scotland, in August 2006, where he presented a paper on "The evolution of diocesan arms in Ireland".

Michael Francis McCarthy KCHS SHA (1950-2007)

Born January 20, 1950. Died August 3, 2007 suddenly at home at Darlinghurst.

Fond son of Norah Elizabeth (Scullion) and the late Francis John McCarthy, brother of Daniel and Thomas and uncle to their children. He was a former administrator at the School of Asian Studies, University of Sydney. He had been a seminarian in his youth but decided not to pursue the priesthood and he went home to Tasmania. He maintained strong links with the Church and in 2002 was invested as a Knight of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre. Recently he had been promoted to Knight Commander.

In 2003 he received a small grant from the National Library of Ireland to produce a book on the coats of arms of the bishops of Ireland. The beginnings of this were presented as a paper at the XXVIIth International Congress of Genealogical and Heraldic Sciences convened at St. Andrews, Scotland in 2006. The completed work is with the Chief Herald of Ireland for review. He was hoping for its completion and eventual publication book at the time of his death.

From an early interest in heraldry encouraged by archbishop Bruno Heim during his appointment to the Court of St James’, Michael established Thylacine Press (named after extinct carnivorous marsupial from his native Tasmania) in 1998 to publish works on ecclesiastical heraldry, which would be given in the historical context in which particular Coats-of-Arms were and are used. At his death he was the author, primary illustrator and publisher of no less than seven books on heraldry.

In addition, in 2001 and again in 2005 he published supplements to the Heraldica Collegii Cardinalium and a CD ROM

updated version of the Armorial of the Australian Catholic Hierarchy was produced in 2005.

A fine artist and a keen scholar Michael's unique style was befriended, encouraged and heavily influenced by the late great

Archbishop Bruno Heim as well as being influenced by the late Dom Anselm Baker, OCSO. Michael could often be seen to

be "difficult" by those who didn't know him well. He had very strong opinions and didn't suffer fools gladly. However, after a

disagreement it was often he who was the first to offer a conciliatory word. Horribly worried about the decaying state of

heraldry in the Catholic Church Michael undertook to effect a revival of sorts building on the foundation laid by Heim. For

those who will miss his work and his contributions to the world of ecclesiastical heraldry his efforts were certainly not in vain

and he was somewhat successful in achieving his goals. It is a shame that his untimely death comes just as he was

beginning to receive the recognition he so richly deserved as one of the world's leading scholars of heraldry as well as one of

its finest heraldic artists. In his Manual of Ecclesiastical Heraldry he left a work of great practical utility to experts as well as

to many amateurs.

Michael was a devout man with a dry but very quick sense of humour. He lived modestly in Darlinghurst and ran his pet project, Thylacine Press, out of his residence. His tiny cramped library was a treasure trove of heraldica! In recent years he began to look forward to a hoped-for return to his native Tasmania. He will be sorely missed by those who knew him personally and those who knew only his magnificent and prolific work.

In recent times Michael had been putting his art work into bound volumes for its protection and with a view to its ultimate bequest to the Vatican Library to which he left “all my library of heraldic books, manuscripts, illustrations, artwork and related material and all copyrights belonging to me whether in published or unpublished works.” He was a member of Heraldry Australia as well as the Society of Heraldic Arts.

May He Rest In Peace

Blaze Away!

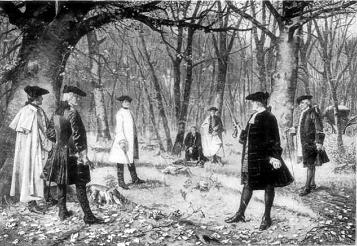

Duelling in Ireland, and that Damned Thing called Honour

“It is incredible what singular passion Irish gentlemen had for fighting each other…and a duel was considered a necessary piece of a young man’s education. The first two questions always asked when he proposed for a lady-wife were: “What family is he of? Did he ever blaze?” (Sir Jonah Barrington 1760-1834)

The death rate for duels fought in Ireland was estimated to be 1 in 4, more than in England, which has a death rate of 1 in 14. A code of conduct for duelling in Ireland, ‘The Practice of Duelling and Points of Honour’ was adopted at Clonmel summer assizes in 1755 by gentlemen delegates from Tipperary, Galway, &c., and presented for general adoption throughout Ireland. This singular national document is still extant, though happily now never appealed to, and these are the only surviving duelling rules in the world.

Ireland’s most prolific and ruthless duellist or ‘fire eater’ was George Robert ‘fighting’ Fitzgerald who was born in the late 1740’s in Turlough Park, in County Mayo. His mother moved to England when he was 5 and he went to Eton and later joined the army. Fighting Fitzgerald was described at the time as being of that “implacable, revengeful and sanguinary nature as to suffer nothing but the blood of the person from whom he supposed he had received an injury, to appease his wrath”. At the age of 38 he was sentenced to death for murder and hanged.

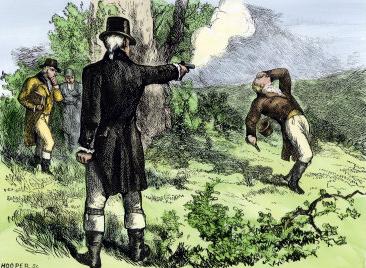

The most notorious Irish duel in the 19th Century was between Daniel O’Connell and John D’Esterre at Bishopscourt near Naas on the 2nd of February 1815. O’Connell had criticised the Dublin Corporation for its neglect of Catholics and described the Dublin Corporation as a “beggarly corporation”. D’Esterre as a member of Dublin Corporation wrote to O’Connell demanding an apology. When he refused this led to a duel. A large group was present at Bishopscourt, and when they were ready D’Esterre fired first and missed. When O’Connell fired he hit D’Esterre, and he died the following day. It was said that O’Connell never forgave himself for the death.

The ‘Blaze Away’ exhibition at Collins Barracks in Dublin includes references to the memoirs of

retired judge Sir Jonah Barrington. He fought a duel as a young man but merely succeeded in

shooting the brooch on his opponent’s chest. Barrington wrote that duelling was “a necessary piece

of a young man’s education”. The first two questions often asked of a suitor concerned his pedigree

and his duelling skills.

Duelling was introduced into Ireland by the new aristocratic and landed elite that came into being

in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. The number of affairs of honour that proceeded to trial

by arms increased perceptibly from the mid 17th century, as ‘Old English’* Catholics and royalists

embraced the honorific precepts of their continental allies and as the ‘New English’ Protestant elite

consolidated its position.

*In the 1500’s the Irish descendants of the Anglo-Norman conquerors referred to themselves as

‘Englishmen born in Ireland’. In the 1620s the term ‘Old English’ made its appearance and

referred to all descendants of the Norman conquers (e.g. FitzGerald, Butler, Stafford, Sarsfield,

etc), as opposed to the recent Elizabethan and Jacobean Protestant settlers, the so-called ‘New

English’. Similar terms—sean Ghaill and nua Ghaill—came into use in Gaelic.

And, as might be expected of those times, religious and political antipathies lay at the root of many duels in late 17th century Ireland.

Following defeat in the 1689-1691 war against multi-national Protestant armies of William of Orange and the resulting Treaty of Limerick, the first effect of disbanding the Irish Catholic Jacobite army was large numbers of Catholic military men wandering about the country without employment or means of living - yet still adhering with tenacity to the rank and feelings of gentlemen. These Catholic gentlemen were naturally susceptible to any slight or insult, and ready, on all occasions, to address them by an appeal to their familiar weapons - the sword or pistol. Their opponents, English and Irish Protestant ‘Williamites’, had been soldiers likewise, and were not likely to treat with due respect those who they perceived as ruined and defeated men. These causes, acting on temperaments naturally hot and irritable, brought on constant collisions, which were not confined to the parties involved, but soon extended through all classes in Ireland. And so it was inevitable that the exodus of many thousands of Irish Catholic Jacobite soldiers (the ‘Wild Geese’) to military exile in the service of France, should bring about a temporary falling off, but the number of duels in Ireland had again risen by the late 1720s.

Duelling peaked in Ireland in the 1770s and 1780s when the confidence of the Protestant elite was at its most assured. This was an era of economic expansion and aggressive political debate. The universal practice of duelling, and the ideas entertained of it, contributed not a little to the disturbed and ferocious state of society in Ireland of those times.

No gentleman had taken his proper station in life until he had ‘smelt powder,’ as it was called; no barrister could go on circuit until he had obtained a reputation in this way; no election, and scarcely an assizes, passed without a number of duels; and many men of the bar, practising in those distant days, owed their eminence, not to powers of eloquence or to legal ability, but to a daring spirit and the number of duels they had fought.

It recorded that Dr. Francis Hodgkinson, Vice-Provost of Trinity College Dublin (died 1840), when asked by one of his students as to the best course of study to pursue, and whether he should begin with Fearne or Chitty, was advised, “My young friend, practise four hours a day at Rigby’s pistol gallery, and it will advance you to the woolsack faster than all the Fearnes and Chittys in the library.”

Sir Jonah Barrington recorded some singular details to illustrate the state of duelling in Ireland, and produced a catalogue of barristers who killed their man, and judges who fought their way to the bench.

Among the barristers most distinguished in this way was ‘Bully Egan’, (John Egan, Chairman of the Royal Hospital, Kilmainham and a resolute opponent of Union with Great Britain, died 1810.) ‘Bully Egan’ was chairman of the Quarter Sessions for the County of Dublin. He was a large, burly man, but of so soft and good-natured a disposition that he was never known to pass a severe sentence on a criminal without blubbering in tears. Yet he fought more duels than any man on or off the bench. Though so tender-hearted in passing sentence on a criminal, he was remarkably firm in shooting a friend. He fought at Donnybrook with the Master of the Rolls, before a crowd of spectators, who were quite amused at the drollery of the scene. When his antagonist fired, he was walking coolly away saying his honour was satisfied; but ‘Bully’ called out: “I must have a shot at ‘your honour’.” On his returning to his place, ‘Bully’ said he would not humour him, or be bothered with killing him but he might either come and shake hands, or go to the devil.

On another occasion ‘Bully’ fought with a certain Mr. Keller, a brother barrister. In those days it was no unusual thing for two opposite counsel to fall out in court in discussing a legal point, to retire to a neighbouring field to settle it with pistols, and then return to court to resume their business in a more peaceable manner. Such an instance occurred at the assizes of Waterford. Keller and ‘Bully’ fell out on a point of law, and both retired from court. They crossed the river Suir in a ferryboat, to gain the County of Kilkenny. Harry Hayden, a large man, and a Justice of the Peace for Kilkenny, when he heard of it, hastened to the spot, and got in between them just as they were preparing to fire. They told him to get out of the way or they would shoot him, and then break every bone in his body. He declared his authority as a Justice of the Peace. They told him if he was St. Peter from heaven they would not listen. They exchanged shots without effect and then returned to court. The cause of their absence was generally understood, and they found the bench, jury, and spectators quietly expecting to hear which of them was killed.

Fitzgibbon, the Attorney-General, who was after-wards Lord Chancellor and Earl of Clare, fought with Curran, afterwards Master of the Rolls, with enormous pistols 12 inches long.

Scott, afterwards Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench and Earl of Clonmel, fought Lord Tyrawly on some affair about his wife, and afterwards with the Earl of Llandaff; about his sister, and with several others, on miscellaneous subjects, and with various weapons, swords and pistols.

Peter Metge, a Baron of the Exchequer, 1784-1801, fought with his own brother-in-law, and two other antagonists.

Marcus Patterson, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, 1770 – 1787, fought three country gentlemen, and wounded them all; one of the duels was with small swords.

Toler, Lord Norbury, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, fought ‘fighting Fitzgerald,’ and several others. So distinguished was Mr. Toler for his deeds in this way, that he was always the man depended on by the Government Administration to frighten a member of the opposition; and so rapid was his promotion in consequence, that it was said he shot up into preferment.

O’Grady, First Counsel to the Revenue, fought Maher and Campbell, two barristers, and several others quos perscribere longum est.

Curran, Master of the Rolls, was as much distinguished for his duels as his eloquence. He called out, among others, Lord Buckinghamshire, Chief Secretary for Ireland, because he would not dismiss, at his dictation, a public officer.

The Right Honourable G. Ogle, a Privy Councillor, and Member of Parliament for Dublin, the great Orange Order champion, confronted Barny Coyle, a distiller of whiskey, because he was a Catholic. Coyle challenged him, because he said “he would as soon break an oath as swallow a poached egg.” The combatants were so inveterate, that they actually discharged four brace of pistols without effect. The seconds did not come off so well as the principals - one of them broke his arm by stumbling into a potato trench. Ogle was as distinguished a poet as a duellist, and his song of ‘Banna’s Banks’ was for 50 years a prime favourite in Dublin in those days.

Sir Hardinge Giffard, Chief Justice of Ceylon, had an encounter with the unfortunate barrister, Bagenal Harvey, afterwards the rebel leader in the county of Wexford during the 1798 Rebellion, by whom he was wounded.

The Right Honourable Henry Grattan, leader of the House of Commons, was ever ready to sustain with his pistols the force of his arguments. He began by fighting Lord Earlsfort, and ended by shooting the Honourable Isaac Corry, Chancellor of the Exchequer. He called him, in the debate on the Union, “a dancing-master,” and while the debate was going on, went from the House to fight him, and shot him through the arm.

So general was the practice, and so all-pervading was the mania of duelling, that even the peaceful shades of the university could not escape if. Not only students adopted the practice, but the Principal and Fellows set the example. The Honourable J. Hely Hutchinson, the Provost, introduced, among other innovations on the quiet retreats of study, ‘dancing and the fashionable arts’. Among them was the noble science of defence, for which he wished to endow a professorship. He was represented in ‘Pranceriana - a collection of fugitive pieces’ (published 1775) as a fencing-master, trampling on Newton’s Principia while he makes a lunge. He set the example of duelling to his pupils, by challenging and fighting Doyle, a Master in Chancery; while his son, the Honourable Francis Hutchinson, Collector of the Customs in Dublin, not to degenerate from his father, fought a duel with Lord Mountnorris.

As if this was not sufficient incentive to the students, the Honourable Patrick Duigenan, a Fellow and Tutor in Trinity College Dublin, challenged a barrister, and fought him; and not satisfied with setting one fighting example to his young class of pupils, he called out a second opponent to the field.

Duelling weapons were generally kept at inns for the use of those who might come on an emergency of honour without having the necessary ‘tools’. In such cases ‘pistols were ordered for two, and breakfast for one’ - as it might and did sometimes happen, that the other did not return to partake of it, being left dead on the field.

No place in Ireland was free from these encounters: feuds were cherished, and offences often kept in memory until the parties met - when swords were drawn and the combat commenced in the public street. In one such case a ring was formed round the feuding parties, and they fought within it like two pugilists in a boxing ring. A spectator described one such encounter witnessed at St Stephen’s Green. One of the combatants was George Robert Fitzgerald (‘fighting Fitgerald’). The parties were walking round the enclosure in different directions and, as soon as they met, they sprang at each other like two game cocks, a crowd collected, and a ring was formed, when some humane person cried out, “For God's sake, part them.”

“No,” said a grave gentleman in the crowd, “let them fight it out; one will probably be killed, and the other hanged for the murder, and society will get rid of two pests.” One of them did thrust the other through the tail of his coat, and he did then long have to exhibit in public, by his uneasy gait, the painful and disgraceful ‘seat’ of the wound.

Among the prominent duellists of the south of Ireland during the late 1700’s, were several whose deeds were still known and discussed by sporting men throughout Ireland and England in the early 1900s. One such gentleman was named Hayes, and called ‘Nosey,’ from a remarkable fleshy excrescence growing from the top of his nose, which increased to an enormous size. It was said to be the point at which his antagonist always aimed, as the most striking and conspicuous part of his person. On one occasion ‘Nosey’ tried in vain to bring an offender to the field, so he charged his son never to appear again in his presence till he brought with him the ear of his antagonist. In obedience to his father’s commands, the son sought out the unfortunate man, seized him, and cut off his ear – and actually brought it back to ‘Nosey’, as a peace offering, in a handkerchief.

Another was Pat’ Power, of Daragle. He was a fat, robust man, much distinguished for his intemperance, and generally seen with a glowing red face. He on one occasion fought with a companion ‘fire-eater’ called Bob Briscoe; and when taking aim, he said he still had a friendship for him, and would show it; so he only shot off his whisker and the top of his ear. Pat’s pistol was always at the service of another who had less inclination to use his own; and when a friend of his declined a challenge, Pat’ Power immediately took it up for him.

Another popular story about Pat’ Power occurred when the Duke of Richmond was touring in the south of Ireland. The Duke knighted many persons, without much regard to their merit or claims. In Waterford he was particularly profuse of his honours in this way. Among his knights were the recorder, the paymaster of a regiment, and a lieutenant. Pat’ Power was in a coffee-house conversing with a gentleman he accidentally met and the topic of conversation was the new knights. Pat’ abused them all, but particularly "a fellow called B---, a beggarly half-pay lieutenant." The gentle-man turned pale, and in confusion immediately left the coffee-room. "Do you know who that is?" said a person present. "No," said Pat; "I never saw him before." "That's Sir J. B---- whom you have been abusing." "In that case," said Pat, with great unconcern, "I must look after my will." So he immediately proceeded to the office of T. Cooke, an eminent attorney, sat down upon a desk stool, and told him instantly to draw up his will, as he had no time to lose. The will was drawn and executed, and then Pat’ was asked what was the cause of his hurry. He explained the circumstance, and said he expected to find a message at his house before him. “Never fear,” said Cooke, “the knight is an Englishman, and has too much sense to take notice of what you have said if it puts his life at risk.” Cooke prophesied truly. (A similar anecdote is told of a Mr. Bligh. It is probable that both he and Pat’ Power, having acquired celebrity in the same way, may have been the heroes of similar achievements.)

When travelling in England, Pat’ Power had many encounters with persons who were attracted by his brogue and clumsy appearance. On one occasion a group of gentlemen were sitting in a box at one end of the room when he entered at the other. The representative of Irish manners at this time on the English stage was a tissue of ignorance, blunders, and absurdities (which is still more or less still the case in English TV and film today); so these gentlemen perceived that when a real Irishman appeared off the stage, he was always supposed to have the characteristics of his class, and so to be a fair butt for ridicule. When Pat’ took his seat in the box, the waiter came to him with a gold watch, with a gentleman’s compliments and a request to know what time it was by the watch. Pat’ took the watch, and then directed the waiter to let him know the person that sent it; he pointed out one of the group. Pat’ rang the bell for his servant, and directed him to bring his pistols and follow him. He put them under his arm and, with the watch still in his hand, walked up to the box. Presenting the watch, begged to know to whom it belonged. When no one was willing to own it, he drew his own old silver watch from his fob pocket, and presented it to his servant, desiring him to keep it; and pocketing the gold one, he gave his name and address, and assured the company he would keep it safe until it was called for. It never was claimed.

On another occasion Pat’ ordered supper, and while waiting for it he read the newspaper. After some time the waiter laid two covered dishes on the table, and when Pat’ examined their contents he found they were two dishes of smoking potatoes. He asked the waiter to whom he was indebted for such good fare, and he pointed to two gentlemen in the opposite box. Power desired his servant to attend him, and directing him in Gaelic what to do, quietly made his supper off the potatoes, to the great amusement of the Englishmen. Presently his servant appeared with two more covered dishes, one of which he laid down before his master, and the other before the persons in the opposite box. When the covers were removed there was found in each a loaded pistol. Pat’ took up his and cocked it, telling one of the others to take up the second assuring him “they were at a very proper distance for a close shot, and if one fell he was ready to give satisfaction to the other.” The parties immediately rushed out without waiting for a second invitation, and with them several persons in the adjoining box. As they were all in too great a hurry to pay their food and drink, Pat’ paid it for them along with his own.

Another of these distinguished duellists was a Mr Crow Ryan. He shouted along the streets of

Carrick-on-Suir, “Who dare say boo” and whoever did dare say so was called out to answer for it.

The feats of another, the celebrated ‘Fighting Fitzgerald’, were still well remembered in Dublin at the

end of the 1800s. He made it a practice to stand in the middle of a narrow crossing in a dirty

street, so that every pedestrian would be forced either to step into the mud, or jostle him in passing.

If any had the boldness to choose the latter, he was immediately challenged.

The deeds of Bryan Maguire continued until the late 1800s ‘to fright the islanders from their

propriety.’ He was a large, burly man, with a bull neck and clumsy shoulders. His face, though

not ugly was disfigured by enormous whiskers, and he assumed on all occasions a truculent and

menacing aspect. He had been in the army, serving abroad, and, it was said dismissed from the

service. He availed himself of his military character and appeared occasionally in the streets in

a gaudy glittering uniform, armed with a sword, saying it was the uniform of his corps. When thus

accoutred he strolled through the streets, looking round on all that passed with a haughty contempt.

Bryan Maguire’s ancestors were among the rulers of Ireland, and one of them was a distinguished

Irish leader in 1641. He therefore assumed the port and bearing which he thought became the

son of an Irish king. The streets of Dublin were formerly more encumbered with dirt than they are

now, and the only mode of passing from one side to the other was by a narrow crossing made through mud heaped up at each side. It was Bryan’s glory to take sole possession of one of those narrow crossings, and to be seen with his arms folded across his ample chest, stalking along in solitary magnificence. Any unfortunate wayfarer who met him on the path was sure to be hurled into the heap of mud at one side of it. The sight was generally attractive, and a crowd usually collected at one end of the path to gaze on him, or prudently wait till he had passed.

Maguire’s domestic habits were in keeping with his manner abroad. When he required the attendance of a servant he had a peculiar manner of ringing the bell. His pistols always lay on the table beside him, and, instead of applying his hand to the bell-pull in the usual way, he took up a pistol and fired it at the handle of the bell, and continued firing till he hit it, and so caused the bell below to sound. Maguire was such an accurate shot with a pistol, that his wife was in the habit of holding a lighted candle for him, as a specimen of his skill, to snuff with a pistol bullet at so many paces’ distance.

The laws by which duelling is punishable were as severe then, as they are now; but such was the spirit of the times that they remained a dead letter. No prosecution ensued, or even if it did, no conviction would follow. Every man on the jury was himself probably a duellist, and would not find his brother guilty. After a fatal duel the judge would leave it as a question to the jury, whether there had been ‘any foul play’ with a direction not to convict for murder if there had not.

Judge Edward Mayne was a serious, solemn man, and a rigid moralist. His inflexible countenance on the bench imposed an unusual silence and sense of seriousness upon the court. A case of duelling came before him on the western circuit, accompanied by some unusual circumstances, which, in the disturbed state of the moral feeling of the time, were considered to be an alleviation. An acquittal was therefore expected as a thing of course. The judge, however, took a different view of the case; he clearly laid it down as one of murder, and charged the jury to find such a verdict. His severity was a subject of universal reprobation, and his efforts to put down murder were considered acts of heartless cruelty. In a company of west coast Irish gentlemen, when his conduct was talked over; some one inquired what was Judge Mayne’s Christian name “I cannot tell what it is,” said another, “but I know what it is not it is not Hugh.”

A few of the other Irish duellists of note include the following:

Richard Brinsley Sheridan (30 October 1751 – 7 July 1816) was an Irish playwright and statesman. In 1772 he duelled with Captain Matthews; as the result of a quarrel between the two concerning Elizabeth Linley, to whom Sheridan was already secretly married. Both men went to Hyde Park in London, but on finding it too crowded repaired instead to the Castle Tavern, Covent Garden, where they fought with swords. Both men were cut, but neither was seriously wounded. Sheridan won this duel as Mathews pleaded for his life after losing his sword. They fought a second duel in July at Kingsdown near Bath to resolve a dispute over the first duel. Both men’s swords broke, and Mathews stabbed Sheridan several times, seriously wounding him, before escaping in a post chaise.

William Petty-FitzMaurice, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne (2 May 1737 – 7 May 1805) was an Irish army officer and statesman; he served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1782 to 1783. He fought a duel in 1780 against a Colonel Fullarton.

Colonel Richard Martin (15 January 1754 – 6 January 1834), was an Irish army officer, politician, and animal rights activist. He fought over a hundred duels with sword and pistol and earned the nickname ‘Hair-trigger Dick’ – in 1783 he even duelled with George ‘Fighting’ FitzGerald in the Castlebar barrack yard. Later in the same year his cousin, James Jordan fought an unsuccessful duel and died of his wounds. As a result of this, Martin refused to duel with Theobald Wolfe Tone, even though he was having an affair with his wife.

George Macartney, 1st Earl Macartney (14 May 1737 – 31 May 1806) was an Irish statesman, colonial administrator, and diplomat. In 1786 he fought a duel with Major General James Stuart; Lord Macartney was wounded.

Charles ‘fighting Charlie’ Stewart, 3rd Marquess of Londonderry (18 May 1778 – 6 March 1854), was an Irish soldier and politician. In 1824 he fought a duel with an Ensign Battier; Battier was a cornet in the Marquess’ regiment. When Battier’s pistol misfired, he declined the offer of another shot and left the field of honour. Battier was later horsewhipped by the Marquess’ second Sir Henry Hardinge. In 1839 ‘fighting Charlie’ fought a duel with Henry Gratton, leader of the Parliament’s House of Commons.

Arthur ‘Iron Duke’ Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington (29 April 1769 – 14 September 1852), was an Irish soldier and statesman, and one of the leading military and political figures of the nineteenth century; serving as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1828 to 1830 and again briefly in 1834. In 1829 the ‘Iron Duke’ fought a duel with Lord Winchelsea, both aimed wide.

Morgan John O'Connell (31 October 1804 – 24 May 1858) was one of seven children of the Irish Nationalist leader

Daniel O’Connell. In 1819 he became the youngest officer in the Irish Legion of Simon Bolívar’s South American

patriot army. He served as a Member of Parliament (in London) representing County Kerry, from 1835 to 1852.

In 1835 he fought a duel with William Arden, Baron Alvanley. Alvanley had asserted that Morgan’s famous father

had been ‘purchased’ by William Lamb, Viscount Melbourne on his accession to the office of Prime Minister –

O’Connell retorted by calling Alvanley “a bloated buffoon”.

Brigadier General Juan Mackenna (26 October 1771 – 21 November 1814) was an Irish officer in the army

of Chilea and hero of the Chilean War of Independence, and created the Corps of Military Engineers of the

Chilean army. He was killed in Buenos Aires late in 1814, after a duel with Luis Carrera.

By the early 19th century the effects of opposition by both the Catholic Church and the Protestant ‘Church

of Ireland’ and rising middle class hostility to the code of honour, along with declining official tolerance, had

brought about a decline in duelling in Ireland. The example of Daniel O’Connell, who refused to accept

challenges after his dispute with Sir Robert Peel in 1817, also contributed to the change. Duels continued to

occur in Ireland during the 1830s and 1840s, but the mood was increasingly censorious and the practice had

ceased by 1860.

One wonders if duelling over matters of honour was still the vogue, would then the modern ‘fashion’ for so

much vicarious litigation be at an end?

All articles Submitted by Michael Doyle