Thomas Plunket – legendary Irish Sniper

1809 - French General ‘dispatched’ at up to 800 Metres

Rifleman Tom’ Plunket, an Irishman serving in the British Army’s 95th Rifles (‘The Rifle Brigade’) during the Napoleonic Wars, was a popular character in that regiment, and is remembered for a feat at the Battle of Cacabelos during General Sir John Moore’s retreat to Corunna (Spain) during 1809. Tom’ advanced alone towards the French and killed Brigadier General Auguste-Marie-Francois Colbert with a single long-range rifle shot (estimated to have been anything up to 800 metres), and then killed another French officer who came to Colbert's assistance with a second shot – using the specialist ‘Baker Rifle’.

One of his comrades remembered him as ‘a smart well-made fellow, about the middle height, in the prime of manhood with a clear grey eye and handsome countenance, a general favourite of both officers and men – besides being the best shot in the regiment’.

Tom’ was noted for ‘being the life and soul of the party’ and a good companion, possessing a quick and wry wit, and after participating in the 1807 British expedition to Buenos Ayres is mentioned as contributing to raising the morale of the corps during the long sea-voyage home by regularly dancing The Hornpipe and the ‘double-shuffle’ (taken to be a ‘Irish jig’) to the applause of all present. A Rifles officer in 1807 said about Tom’ that ‘Plunket … was a bold, active, athletic Irishman and a deadly shot - but the curse of his country was upon him.’ The ‘curse’ in question here was habitual drunkenness and saw Plunket’s promotions to corporal and sergeant lead each time to a flogging and a reduction back to the ranks.

Tom’ Plunket’s reputation as a ‘crack shot with a rifle’ originated from his exploits during the British expedition to capture Buenos Ayres in July 1807. Although the expedition was a disaster for the British, during the fighting in the city Tom’ spotted a particularly active Spanish officer and shot him in the thigh at long-range, receiving the plaudits of his company for doing so (though it seems Tom’ came in for a bit of censure as the officer in question was under a flag of truce at the time). It is also claimed that Tom’ shot up to 20 Spanish soldiers from the roof of the Santo Domingo Convent in Buenos Ayres, and through those exploits he became well known as one of the few men in the two battalions of the 95th who could shoot a rifle ‘with unerring accuracy at an extended distance of over 200 yards’.

Tom’s physical strength shouldn’t be under-rated either: punished by being forced to carry an iron cannonball, it was noted that instead of suffering under the weight, Tom simply ‘tucked it under his arm’.

Tom’s wit and charm was fully demonstrated in March 1809 when as a corporal he was detached from Hythe Barracks to recruit from the militia then stationed in Dover: dancing a jig on the top of a beer barrel in a public house (local bar), the top of the barrel collapsed and Tom’ dropped straight down into the beer to disappear – and then, before the militiamen could burst into laughter at the mishap, Tom’ leapt out soaking wet and climbed into the chimney. Emerging from the chimney covered in soot, he then exclaimed “Damn your pipe-clay; here I am ready for The Grand Parade!” The sombre very dark green uniform of the 95th Rifles had already gained them the nickname of ‘The Chimney-Sweeps’ and, in referring to the bugbear of redcoats – the ‘pipeclay’ used for whitening uniform belts and cross-straps – Tom’s quick wit scored an immediate hit and brought in several new recruits for the Rifles.

In late July 1808, 1st battalion of the 95th Rifles left Dover for Spain, and Tom’ and his comrades joined that rather battered British army fighting against Napoleon’s forces in what became known as the ‘Peninsula Campaign’.

The ‘Retreat to Corunna’ began on Christmas Day 1808 just beyond Sahagun, and saw Tom’ Plunket in the ranks of the 1st of the 95th, as part of the Reserve Division who became the rearguard for the withdrawal of the main body of the British Army after Astorga.

The French finally discovered the retreating British and the pursuit began.

Travelling at speed, by the 1st of January 1809 in cold, wet weather the ‘main body’ of the hard-pressed retreating Brits had reached the town of Villafranca, which was one of the main supply depots for the British Army at the time. The British rearguard was then in a small village named Cacabelos, only about half a day’s march behind the main body of the retreating British army.

Upon reaching the mountains, the rain turned to snow and the road was marked by a succession of corpses of British soldiers and horses, with broken wagons and carts lying in the ditches. Many villages along the road were deserted, with smashed furniture and the smoking remains of looted houses evidence of collapsing morale amongst the retreating Brits. Houses in some villages were discovered by the French to be hiding British soldiers and ‘camp-followers’ – who were all either sound asleep or, more often, drunk in an attempt to escape from the terrible weather conditions, during what was without doubt a very punishing forced march.

J P Beadle’s famous painting, ‘The Rearguard’ depicting General ‘Black Bob’ Craufurd and a party of riflemen of the

95th turning to face a French pursuit, somewhere on the road between

Astorga and Orense, the icy conditions depicted are typical of Galicia during the ‘retreat’

In Villafranca on the 2nd of January, General Sir John Moore witnessed the disintegration of his army. An overnight riot involving hundreds of hungry or drunken British soldiers had ransacked all the storehouses and destroyed the town. In the morning, under a pall of thick smoke the town echoed to pistol-shots as emaciated horses were shot and the artillery wagons broken up with their ammunition thrown into the river; daylight revealed a fearsome sight of upturned barrels of rum and wine, bread trodden into the mud, broken baggage carts, new clothing and army blankets strewn about, churches broken into and used as barracks and the bodies of several murdered civilians seen in the streets. Starving and diseased Spanish soldiers from the ‘La Romana’ infantry division who had struggled as far as Villafranca hoping for relief in the form of food, clothing and boots simply gave up and died in droves to add to the misery.

Riding six miles to the east, Sir John Moore arrived at Cacabelos and, after consulting with his senior officers, made a prophetic speech to the soldiers of the British rearguard concerning the need for order and discipline before he returned to Villafranca; and, in reply to this speech, the soldiers that night plundered and ransacked Cacabelos looking for drink.

NOTE: The speech by Sir John Moore was described by one British officer as ‘formidable and pathetic’ and Sir Edward Paget himself snorted that any appeal to a British soldiers’ finer feelings was simply a waste of time and they could be governed only by the lash and the noose. Sir John Moore’s speech at Cacabelos included the rather prophetic sentence - using hindsight - that he was so ashamed of his soldiers that he “hoped the first cannonball fired by the enemy may take me in the head!” Just two weeks later - at the point of victory - he was mortally wounded by a roundshot from the French artillery.

Next morning, a furious Sir Edward Paget - commanding the British Reserve division – gave orders for severe punishment, in an attempt to prevent the rearguard dissolving into the anarchy witnessed at Villafranca. In freezing weather, just before dawn, most of the soldiers of the Reserve were ordered into a ‘hollow square’ formation on a hill just north of the village, out of sight of the main road. Troopers of the 15th Hussars and a strong force of two companies of Riflemen from the 95th were sent along the road to relieve the frozen pickets and vedettes that had spent the night in the open keeping a watch for any French troops approaching from Ponferrada, a small town about five miles away. Paget then proceeded with the courts-martial and the floggings. As the punishments were carried out, troopers of the 15th Hussars arrived several times to report that French cavalry patrols were now in sight along the road from Ponferrada.

Paget received each report with a nod and a simple “Very Well … ”

After several hours had passed, all that remained for Paget to do was to hang two soldiers convicted of robbery. As Paget watched the ropes being thrown over tree branches, the first popping sounds of musketry came from over the hill to the east.

General ‘Black Jack’ Slade – one of the British cavalry brigadiers – then arrived to report that his forward vedettes were coming under some pressure and starting to pull back. Paget already had a low opinion of Slade and replied to the effect “I am sorry for it. But - this information is of a nature that would induce me to expect a report from a private dragoon rather than you. You had better go back to your fighting picquets, Sir - and animate your men to a full discharge of their duty.”

Slade rode off ; and the hangmen were watching Paget waiting for the signal to begin the execution. Paget was seen by one officer to be visibly ‘suffering under a great excitement’; Paget finally looked up and bellowed out “My God! Is it not lamentable to think that instead of preparing the troops confided to my command to receive the enemies of my country I am preparing to hang two robbers? But - even though that angle of the square be attacked, I shall execute these two villains in the other!”

A strange silence ensued for two minutes, broken only by an increasing number of rifle and carbine shots from the east. Paget looked down from his horse at the assembled troops and spoke again: “If I spare the lives of these two men, will you promise to reform?” The silence continued until prompted by their officers by nods and nudges, the soldiers began to murmur ‘Yes!’ until it was shouted across the square. Paget then ordered the troops to dismiss – but as they marched back towards the village, the first French cavalry troopers appeared over the crest of the hill half a mile to the east.

The French were led by a man on a white horse ; a remarkably young General of Brigade named Auguste-Marie-Francois Colbert who had taken over the pursuit of the retreating Brits after his predecessor had been taken prisoner by the British and their ‘King’s German Legion’ cavalry. (A few days before, General Lefevbre-Desnouettes had been captured while attempting to lead his French troops across the Esla River at Benevente when, during the attack against the British rearguard, the French cavalry had come off the worse.)

The pursuing French cavalry had an estimated strength of twenty squadrons, but the column stretched back many miles.

And so, the immediate pursuit of the Brits was headed by Colbert, with his own light cavalry brigade of the VI Corps, comprising the 15eme Chasseurs a Cheval and the 3eme Hussards, (somewhere between 450 and 500 mounted troopers).

Having caught up with the infantry of the British rearguard, Colbert then decided to attack at once in an attempt to at least cut some of them off from the river bridge.

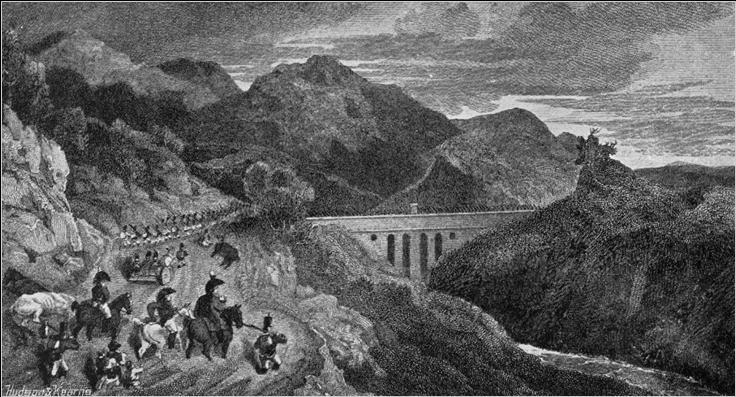

The approaches from Nogales, over the Sierra de Bierzo, to the Constantino bridge

As the vedettes of the 15th Hussars and the Riflemen retired towards Cacabelos, Colbert arranged the squadrons of his nearest cavalry for an advance. Some of the Riflemen of the 95th were sent to support the vedettes of the 15th Hussars, who were watching the road to Ponferrada, and these Riflemen were observed to be ‘running back with difficulty’ – cold, exhausted and hungry men who, in the circumstances, did well to be able to run at all.

Most of the British rearguard were then ordered to move through the town of Cacabelos and across the bridge, onto the west bank of the river.

The light company of the British 28th Regiment of Foot was drawn up on the eastern river bank to cover the passage over the bridge of the six guns of the Royal Horse Artillery. As the artillery rumbled across the bridge towards the western hill, followed by the light company of the 28th Foot, an indication of panic ensued as the first British troopers and the fastest Riflemen began to appear in Cacabelos … with the French hot on their heels. The approaches to the bridge on the east bank were quickly blocked by a crowd of British soldiers and horses struggling to cross the bridge before the French arrived, amongst whom Sir John Moore and his staff became entangled.

Last in line in this confusion, troopers of the 15th Hussars vedettes rode in onto the rear of two companies of the 95th Rifles, who were also trying to cross the bridge. And, as the 15th Hussars were forced to turn and fight, they were overwhelmed by the French cavalry. The French then began to round up the wounded, and also about fifty exhausted Riflemen of the ‘picquet’ who were too slow coming down the hill, and been overtaken by the French before they could reach the bridge.

As a consequence of the general disorder of the British, Colbert noticed that his troopers were also becoming disorganised and dispersed – and they were coming under British fire from the houses near the bridge, and the bridge itself was still obstructed by green-jacketed Riflemen and hussars … so he immediately called the French cavalry to fall back.

With the last of the British rearguard; the light company of the 28th Foot, some of the 15th Hussars and five companies of the 95th Rifles – two of these in a state of disorder - Colbert thought there was a good chance he could capture or destroy some part of the British Reserve by crossing the river, even without the French infantry or artillery in support … if he could just reform his cavalry brigade quickly. Leaving a small dismounted vedette of several Chasseurs on the western outskirts of Cacabelos to observe the British and the approaches to the bridge, Colbert then rallied the rest of his French troopers a short distance away to the north of the village.

Sir John Moore had arrived from Villafranca during the first French advance and, at close-hand, witnessed the British confusion at the bridge as both he and his Military Secretary were involved in that ‘jumbled mess’ … and the two of them had to flee as the French were almost upon them, with both men just narrowly avoiding capture.

In the midst of this general tide of confusion, General Slade appeared once again and asked Sir John Moore if he could make a report given to him by Colonel Grant (one of the officers in Slade’s command). A still-seething Moore rather sarcastically asked General Slade, “how long have you been serving as Colonel Grant’s messenger?”

The British 52nd Regiment of Foot joined the 28th Foot on the western hill, standing in line; waiting for their turn to move off.

The three companies of the 95th Rifles which had previously been quickly ‘herded’ into houses near the bridge, and into the gardens and vineyards on both banks, now received orders to pull back as the six guns of the Royal Horse Artillery clattered down the road and up the western hill to take up positions to cover the bridge.

The Light Company of the 28th Regiment of Foot had followed the artillery over the bridge and in doing so escaped the ensuing general confusion. As the western hill was so steep, the Light Company of the 28th were drawn up directly below the artillery on a lower slope, and were able to fire their muskets in the direction of the bridge, and were supported a short distance away to the left by the rest of their battalion who were blocking the road to Pieros and Villafranca, together with the 52nd Foot on their right.

As the French cavalry withdrew to reform, Colbert was well mounted and actively encouraging his cavalry.

The three companies of the 95th Rifles took up positions on the east bank – and were then joined by the two companies that had been caught up in the turmoil at the bridge.

The 95th then ordered their pickets out of the gardens on both sides of the bridge, and fell back to take up new positions on the lower slopes of the western hill, overlooking the road to Pieros.

In the meantime, Colbert had reformed his French cavalry brigade and was prepared for a second attack on the bridge. As the first of the French cavalry advanced, the British artillery on the western hill prepared to open fire ‘in enfilade’ by sending roundshot bouncing across the frozen fields towards them.

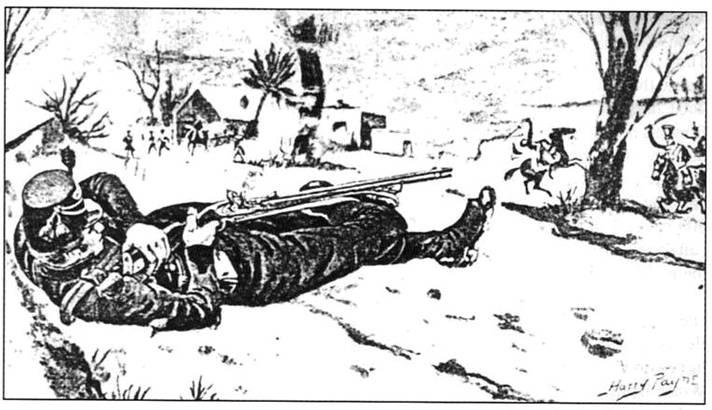

Tom’ Plunket was with his company of the 95th Rifles on the western bank of the river, and was in a ‘bad temper’ from the events so far … including seeing the French cavalry cut down or take prisoner a good number of his Riflemen comrades. Seeing the steady advance of the French cavalry preparing to again ‘charge’ - with Colbert conspicuously out in front once again – Tom’ is said to have suddenly run forward, laid down on his back in the mud and snow, and taken careful aim at Colbert with his rifle.

Tom’ fired, and Colbert fell backwards off his horse – dead. By the time Colbert’s aide rode up and dismounted to look at Colbert’s body, Tom’ had reloaded his rifle and, taking careful aim, calmly shot him dead too. This second feat showed that the first shot had not been a fluke, and the shots were at a sufficiently long distance to impress others in the 95th Rifles, whose marksmanship (with the Baker Rifle) was far better than the ordinary British infantry – who were armed with a ‘Brown Bess’ musket and only trained to shoot with volley fire into ‘an area target’ of a body of men, at 50 metres.

A dozen furious French cavalrymen then charged towards Tom’ in revenge, but the plucky Irishman ran back to his company to the cheers of his comrades.

Before reaching the bridge, the French cavalry came under fire

from round-shot directed at them by the British Royal Horse

Artillery and, as they reached and crossed the bridge, bullets

from the 28th, 52nd and 95th tore into them from both flanks and

in front.

The fastest – or the angriest – of the French horsemen galloped

across the bridge, and some of them survived the cross-fire and

the ensuing volley to reach the light company of the 28th – where,

for a few minutes, sabre clashed with bayonet. But, brave as it

was, it was still unlikely that a handful of French light horsemen,

arriving piecemeal on tired horses, did much to upset the ordered

ranks of the waiting redcoats.

The rest of the battalion of the 28th Regiment of Foot then

advanced, and the French cavalry were then forced to retreat ba

ck across the bridge, to avoid being encircled, and so came under

the same heavy fire again.

A young British officer of the 28th Foot watched wide-eyed with

horror as a dead Frenchman with a boot caught in a stirrup was

dragged through the mud to the river by his terrified horse, his bal

d head bouncing bloodily up and down on the frozen ruts of the

roadway: many years later, when the same officer was an older

and wiser man and had seen many other horrors of war and been able to forget most of them, he still could not rid himself of this single terrible remembrance …

Sir John Moore and Sir Edward Paget, on the western hill above the road to Villafranca, watched the survivors of the second French cavalry charge retire back across the bridge and probably realised that these gallant French troopers were capable of doing no more that day – but, in the middle distance, they could both clearly see a long line of French infantry and still more French cavalry marching over the crest of the eastern hill beyond Cacabelos, approaching along the road from Ponferrada.

Just over an hour later an attack by these French troops came in at two locations: La Houssaye sent in fresh cavalry and infantry skirmishers to cross the river by a ford a short distance downstream from the bridge, and another attack by the infantry of General Merle’s division was aimed at the bridge a la baionette.

Some of the 95th Rifles at the bridge were sent south along the riverbank to deal with French at the ford, closely supported by the 52nd Foot.

As the French infantry swung around Cacabelos and approached the bridge and the apparent gap left by the 95th and 52nd as they moved south, they were fired on by the six guns of the Royal Horse Artillery, which forced the French columns to withdraw back around the village before reaching the bridge.

The French attack at the ford also fell back after a short exchange of musketry. And, those French who managed to get back across the river there, using the ford, were then hotly pursued on their return journey by invigorated and energetic soldiers of the 95th and the 52nd.

The French then seemed to lose heart, perhaps because as the French units reformed on the eastern bank, they probably heard of Colbert’s death and the failure of the two French cavalry charges. By this time it was getting pretty dark, and it is more than likely that the French troopers realised they had just ‘bitten off more than they could chew’ in the face of an unexpected and determined British resistance from strong defensive positions.

All firing slowly died away with the fading of daylight, at just after 4.00pm.

Sir Edward Paget ordered the British Reserve division to form up a few hours after dark and, at about 10.00pm that night when the pickets were called in, they marched through Pieros going west towards Villafranca, with no sign of a French pursuit.

Both sides lost around 200 men killed or wounded that day, plus fifty or so British prisoners taken by the French. However French morale had taken a beating, and the morale of the British Reserve force had rocketed – to be duly lowered by a degree or two when the Brits reached Villafranca, where no attempt at all had been made to tidy the place up. And, as the British Reserve division passed through the town they saw, by the light of bonfires, a scene of utter desolation with British soldiers still lying drunk in the streets.

Tom Plunket’s reputation as a ‘model soldier’ did suffer later; losing his stripes twice, through drunken misbehaviour, during Peninsula campaign – but there still remains the simple fact that when Tom’ killed the driving force of the French cavalry at Cacabelos, he tipped the balance of the battle in favour of the British Reserve division and no doubt saved a lot of lives by doing so.

Tom’ Plunket had lots of other adventures, many of which are recalled by Edward Costello in his book ‘Adventures of a Soldier’, one of many ‘rifles memoirs’ which followed after the Napoleonic war – but it was not published until 1852. It is confirmed in the book that Plunket did shoot Colbert by lying on his back to take aim. And it is hinted later in the book, that ‘shooting French officers’ in a similar fashion may have become Tom’s ‘speciality’ and occurred yet again on more than one occasion during the battle of Corunna on the 16th of January 1809.

Edward Costello served from May 1809 in the 1st Battalion of the 95th Rifles with Tom’ during the Peninsula War. They served in the same company and appear to have been good friends. Tom’ apparently managed to get through the rest of the Peninsula War without a scratch, but he was wounded at Waterloo when a bullet badly scarred his forehead. And, though they passed within a few yards of each other at Waterloo, it is not recorded if Sir Edward Paget – then The Earl of Uxbridge, commanding the Anglo-Dutch Cavalry – saw or remembered Tom’ Plunket.

After Waterloo, Tom’ was ‘invalided out’ with an army pension, but expressing his disgust at the miserable size of the pension, in such a manner to the Lords’ Commissioners, that they were then inclined to strike him off the list altogether.

Without employment or money, Tom then married an Irish girl named Elizabeth MacDermottroe, who did have an army pension – as her face had been horribly disfigured by the explosion of an ammunition wagon during the fighting around Quatre Bras, in June 1815 at the Battle of Waterloo. They went off together to Ireland in late 1815.

However, in desperate circumstances, Tom’ was soon forced to re-enlist as a redcoat – but described at the time as ‘a very bad character and nearly worn out in the service’. His old commanding officer Sidney Beckwith recognised and remembered him, and intervened to secure him a pension of a shilling a day.

In 1817 Tom’ subsequently accepted the Government’s offer of money and a grant of land in Nova Scotia (Canada) to old soldiers who wished to settle there; but Tom’ evidently made an awful settler and so returned to Britain, finally reduced to peddling matches, ribbons and pins on a street-corner.

Tom’ Plunket – who would by then have been in his early fifties – died suddenly some years later; with a groan, he staggered a few steps before dropping dead in a Colchester street, during what is presumed to have been a massive heart attack.

Publicity in 1839 about his adventures – especially ‘Plunket’s Shot’ – caused several retired military men then living in Colchester to report his death in 1840 to newspapers. Money was raised by these retired officers; enough to pay for Tom’s funeral and a ‘handsome’ headstone, with £20 left over for his wife.

Tom Plunket’s wife unexpectedly visited Costello in 1840 (who was then serving as a Warder at the Tower of London) to inform him of Tom’s death – which seems to have come as something of a shock to Costello – before she emigrated to America.

Elizabeth re-married in America and evidently gave birth to several children (there is some evidence to indicate their descendants are still living there today).

…………………………………………………………………………………..

The Baker Rifle

Colonel Coote Manningham, who was responsible for establishing the Rifle Corps of the British Army, influenced the initial designs of the Baker. Baker was provided with a German Jager rifle as an example of what was needed. The British production rifle also had a metal locking bar to accommodate a 24-inch sword bayonet, similar to that of the Jager rifle. The Baker was 45 inches from muzzle to butt, 12 inches shorter than the Infantry Musket, and weighed almost nine pounds.

A lighter and shorter carbine version for the cavalry was introduced, and a number of volunteer associations procured their own models, including the Duke of Cumberland’s Corps of Sharpshooters, which ordered models with a 33-inch barrel, in August 1803.

During the Napoleonic Wars the Baker was reported to be effective at long range due to its accuracy and dependability under battlefield conditions. In spite of its advantages, the Baker Rifle did not replace the standard British musket of the day - the ‘Brown Bess’ – but was instead issued officially only to Rifle Regiments. In practice, however, many infantry regiments acquired Baker Rifles for use by their light companies during the Peninsular War. These units were employed as an addition to the common practice of fielding skirmishers in advance of the main column, who were used to weaken and disrupt the waiting enemy lines (the British also had a light company in each battalion that was trained and employed as skirmishers but these were only issued with muskets). With the advantage of the greater range and accuracy provided by the Baker Rifle, British skirmishers were able to defeat their French counterparts routinely and in turn disrupt the main French force by sniping at commissioned officers and sergeants.

The rifle was used by what were considered to be elite units, such as the 60th Regiment (The Kings Royal Rifle Corps) and the 95th Regiment (The Rifle Brigade), that served under the Duke of Wellington between 1808 and 1814 in the Peninsula War, in the War of 1812, and again in 1815 at the Battle of Waterloo, as well as by the light infantry of Britain’s King’s German Legion. The rifle was also supplied or privately purchased by numerous volunteer and militia units; these examples often differ from the regular issue pattern.

The Noble Society of Celts, is an hereditary society of persons with Celtic roots and

interests, who are of noble title and gentle birth, and who

have come together in a search for, and celebration of, things Celtic.

"Summer Edition 2009"

All articles Submitted by Michael Doyle

The Irish Legion of South America

Liberators of Chile, Venezuela, Columbia, Peru, and Bolivia

Battle of Carabobo by Martin Tovar y Tovar (1827 – 1902)

[This image (or other media file) is in the public domain because its copyright has expired. This applies to the United States, Australia, the European Union and those countries with a copyright term of life of the author plus 70 years.]

Most Irish-descended people are well aware of the huge Irish Diaspora in America, Australia, Canada, England, New Zealand, Scotland (Sean Connery, Billy Connelly, et al), and Southern Africa. Many however are oblivious to the Irish Diaspora in Latin America and the part that many Irishmen, and those of Irish decent, played in those countries’ fight for freedom against Spanish colonial rule.

Probably the most famous Irishman ever to reside in Latin America was William Lamport, better known to most Mexicans as ‘Guillen de Lampart’. He was one of many Irishmen who have gained fame in Mexico for their adventurous lives, and was a precursor of the Independence movement, as well as the author of the first proclamation of independence in the New World. He was born in 1615 at Wexford in Ireland and, as a young man, he took refuge in Spain – like so many thousands of other Irish ‘Wild Geese’ during those times of English invasion and genocide. History tells us that a scandalous love affair caused him to flee from Spain to Mexico (Nueva Espa ña), where he was moved by the poverty and degradation of Indians and African slaves. Ultimately, he was accused of plotting a war of independence against the Spanish colonial government, which led to his imprisonment. After ten years, he escaped and lived as a fugitive, continuing his life and love affairs in ‘New Spain’. Eventually, he was captured and sentenced to death by the Spanish Inquisition, launching his name into legendary martyrdom. At the time, his adventurous and charitable lifestyle had such an impact, that the citizens of New Spain dubbed him the famous El Zorro. His statue stands today in the Crypt of Heroes beneath the Column of Independence in Mexico City. (There are also monuments in Mexico City paying tribute to those Irish who fought for Mexico in the 1800’s.)

Bernardo O’Higgins, the Chilean revolutionary, was born in Chillán in 1778 and was the illegitimate son of Ambrosio O’Higgins, Spain’s Irish-born viceroy of Chile and Peru. The younger O’Higgins played a great part in the Chilean revolt of 1810-1817, and became known as the ‘Liberator of Chile’. During 1817-1823 he was the new republic’s first president. His exhortation “Live with honour or die with glory. He who is brave, follow me” is still honoured in modern Chile.

Of all the leaders of the ‘patriotic armies’ that fought to end Spanish rule in South America the most famous is undoubtedly Simon Bolivar (‘The Liberator’), and he came to rely heavily on the Irish ‘wild geese’ that fought for him during his campaigns – he later referred to the Irish as “Salvadores de mi Patria!” (saviours of my country).

The story of Simon Bolivar’s ‘Irish Legion’ that won fame in Venezuela, Columbia, Peru, and Bolivia actually starts in London in 1817 – as the wars of liberation in South America provided many ex-soldiers of the British army (the biggest proportion of whom were Irish) with an opportunity to continue their military careers and escape from the prospect of inactivity (and poverty) at home. The Brits were drastically reducing the strength of their army after the defeat of Napoleon at the battle of Waterloo. And, as one of the Duke of Wellington’s former Irish officers put it after being retired upon half-pay, it was ‘......South America, flags, banners, glory, and riches!’

The ‘British’ volunteers (the largest proportion was Irish and, given the composition of the British army of those times, this was no coincidence) were recruited in London in 1817 by one of Bolivar’s agents, Luis Lopez Mendez. During April 1817 Mendez had asked for an interview at the British Foreign Office, perhaps to hear what the official view would be to the recruitment of British volunteers, and it was around this time that the victor of Waterloo, Arthur Wellesley Duke of Wellington (a Protestant Irishman), arrived in London on a visit from his army occupation duties in Paris. It has since been suggested that this was no coincidence, and that Wellington was already putting his mind to the problem of disbanding his large army of occupation. It is almost certain that Wellington gave more than a passing thought to the possibility of a large number of his men joining the patriot armies in South America as a way of easing his problem of demobilisation.

The Irish volunteers were encouraged by promises of pay equivalent to what they were receiving in the British army and by promotion to one rank above that which they had held in Britain’s service. Pay was to commence upon arrival in Venezuela, and when the call was heard on the streets of London and Dublin thousands began to volunteer for the expedition and soon the first regiments began to take shape, amongst which were the 1st and 2nd Venezuelan Hussars and the 1st Venezuelan Lancers. One of the first to join the ranks of the 2nd Venezuelan Hussars was Daniel Florence O’Leary, who later rose to the rank of general after many years service as aide-de-camp to Simon Bolivar, and whose memoirs are now recognised as one of the most important sources for the study of the independence campaigns in South America.

The first major detachment of ‘British’ volunteers destined for Venezuela were:

* the 1st Venezuelan Hussars - 30 officers and 160 non-commissioned officers,

commanded by Colonel Gustavus Hippisley (an Englishman);

* the 2nd Venezuelan Hussars (the ‘Red Hussars’) - 20 officers and 100

non-commissioned officers, commanded by Colonel Henry Wilson (an Irishman);

* the 1st Venezuelan Lancers - 20 officers and 200 non-commissioned officers,

commanded by Colonel Robert Skeene (an Englishman);

* the 1st Venezuelan Rifles - 37 officers and 200 non-commissioned officers,

commanded by Colonel Donald Campbell (a Scotsman); and

* the Brigade of Artillery -10 officers and 80 non-commissioned officers,

commanded by Colonel Joseph Gilmour (an Irishman) with five 6-pounders and

one 5½ howitzer.

The formation of the regiments was not without problems, and it wasn’t long before the Spanish authorities in London began their protests to the British government, calling on it to prohibit British subjects from taking part in the contest between Spain and the South American patriotic armies. However, in spite of many problems, the 5 ‘British’ volunteer regiments comprising the first contingent finally embarked for South America in December 1817. Unfortunately for the 1st Venezuelan Hussars, under Colonel Skeene, their transport ship the ‘Indian’ went down in a storm with a loss of 300 lives, thus depleting the force somewhat. A second contingent of volunteers was soon dispatched from England, which was also largely composed of Irish veterans of the Napoleonic wars.

In Dublin, Daniel O’Connell, the brilliant orator and lawyer who was leading the Irish Catholics in their campaign for civil rights and Irish Independence from Britain, wrote to Bolivar that he saw The Liberator’s war with Spain as paralleling the Ireland’s own struggle with England. He roused moral and financial support for Bolivar and sent his 15 year old son, Morgan, to fight for South America’s liberation and Bolivar’s grand vision for the continent.

“Hitherto,” O’Connell wrote to Bolivar, “I have been able to bestow only good wishes upon that noble cause. But now I have a son able to wield a sword in its defence, and I send him, illustrious Sir, to admire and profit by your example.”

With this letter in hand, Captain Morgan O’Connell landed at Margarita Island off the coast of Venezuela on the 12th of June 1820 and presented himself for duty as the Irish Legion’s youngest officer.

The struggle in far-off Venezuela evoked an age-old Irish tradition of sending its sons to serve in foreign wars. Bolivar’s cause had struck a romantic chord in O’Connell, enabling him to set aside his well-known antipathy to bloodshed.

As O’Connell went, so went the rest of Ireland. In Dublin, supporters organized the ‘Irish Friends of South American Independence’ society, and 2,000 of Ireland’s leading citizens attended that society’s banquet on the 19th of July 1819. Attracted by posters and handbills, eager young men volunteered for the Irish Legion. Daniel O’Connell sponsored fundraising events, and Mrs. O’Connell honoured the Irish Legion’s dashing cavalry regiment with a public presentation of battle flags.

Not all those attracted to the Irish Legion shared the O’Connell's noble motives. Indeed, an embarrassing problem began with the Legion’s ‘commander’, John Devereux (County Wexford) – who had been living in exile in the USA following his participation in the bloody 1798 Irish Rebellion. A self-styled major-general in the Army of Venezuela, Devereux had no formal military training or experience. Outfitted in a dazzling uniform and carrying a jewel-studded sword, Devereux was a poster-perfect recruiting agent. But when his Irish recruits sailed off for war in South America, Devereux remained behind, living handsomely off the fees he charged Irish officers for their commissions in the Legion.

While working as a supercargo - the commercial officer on a merchant ship - several years previously, Devereux met Bolivar when his vessel called at the Colombian port of Cartagena in 1815. Sensing a business opportunity, Devereux offered to raise a force of 5,000 men with arms, ammunition and stores. Bolivar promised him $175 for each soldier who reached Venezuela.

After returning to Ireland and ingratiating himself with Danielle O’Connell, Devereux exploited the Irish patriot’s prestige to further his moneymaking scheme. While the Irish Legion attracted many professional soldiers, Devereux also opened the ranks to ne’er-do-wells and idlers. Although he knew that Bolivar’s local soldiers served without pay, Devereux promised Irish recruits one-third more than the British Army was paying. And he sealed the deals with visions of land grants and cash bonuses at campaign’s conclusion.

O’Connell could not so easily dismiss the misadventures of his protégé John Devereux. Returning veterans of the Irish Legion accused Devereux of cowardice, greed and betrayal. Bolivar’s naval commander wrote to the Dublin newspapers, bitterly describing Devereux’s recruits as bandits. Embarrassed and in fear for his life, Devereux finally set out for Venezuela.

After searching fruitlessly for his Irish Legion at the port of Riohacha in Columbia and at the British colony of Jamaica, Devereux reached Margarita Island off Venezuela. Here, at least, the rogue’s reputation had not preceded him. Strutting around in a field marshal’s uniform, and waving his jewel-encrusted sword, he threatened personal vengeance on every Spaniard in South America.

Despite his record, the wily Wexford man managed to re-ingratiate himself with Simon Bolivar. On reaching Bogota, Devereux was made a member of Bolivar’s general staff. Displaying a blind spot equal to Daniel O’Connell’s, Bolivar forgave the con man and confirmed him in the rank of major general. Undeterred by the fact that he had not set eyes on his troops since they left Ireland, Devereux busied himself collecting the commissions promised him for the men and materiel of his Irish Legion.

Throughout his service under Bolivar, Devereux managed to arrive at engagements too late to see combat, but never too late to claim credit for victory. Later, Devereux filed a disability claim for injury to his eyesight during field service in Colombia, even though he was safely in Bogota at the time.

By 1824, when he returned to Europe, Devereux had amassed a large fortune for those times of £150,000. Despite this ‘splendid sufficiency,’ as he described his ill-gotten gains to Daniel O’Connell, he busied himself promoting mining ventures and other moneymaking schemes in South America. In stark contrast to his recruits, Devereux lived to the ripe old age of 82, when he died in the fashionable Mayfair district of London’s wealthy west end.

Nonetheless, in spite of all John Devereux’s mischief, and after a 4,500-mile sea voyage from Dublin about 1,000 men of the ‘Irish Legion’ did reach Margarita Island, off the coast of Venezuela, in August 1819. However they paid very dearly for Devereux’s double-dealing; Venezuelan officials, unaware that the Irish were coming, had readied neither housing nor rations. Bolivar, with barely $1,000 in his treasury, could not pay the Irishmen. The island was a hot, unhealthy place for fair-skinned European soldiers, with unsuitable quarters and a lack of water.

Food was so scarce that many of the Irish cut the buttons from their uniforms in order to pass them off as money to the local people in payment for bread and fruit. To make matters worse, typhus fever, which was raging in England and Ireland at the time, broke out and others were struck down by yellow fever. The combination of heat, humidity and impure water provided a perfect breeding ground for disease. Dysentery, typhus and yellow fever decimated the ranks. Uniforms and boots deteriorated quickly, leaving many men barefoot and half-naked. Insect bites and thorn punctures turned infectious, and surgeons amputated limbs wasted by tropical ulcers and gangrene. The Margarita’s sandy beaches became Irish graveyards. Every day, burial parties carried the bodies of 10 to 20 men to the shore, interring them in crude coffins fashioned from wooden barrel staves. Some soldiers drowned their sorrows in drink, while others flouted military discipline or deserted.

Within five weeks some 250 men, women and children had died. By this time, Gilmour (one of the Irish colonels) had recruited about 100 natives and after some intense drilling had managed to weld them into a fairly cohesive unit. They sheltered beneath tents made from canvas which had been used by the British army in the ‘Peninsular War’ during the Wellington’s campaign against the French in Spain. Language barriers inhibited communication with their new commander, General Mariano Montilla, who spoke no English. What the Irish Legion wanted most of all, however, was a spell of action and it came as a great relief when, on July 14th, 1819, the whole force of about 1,000 ‘British’ and 300 natives at last sailed for the mainland of Venezuela.

Bolivar employed the Irish Legion as an amphibious raiding force, harassing royalist garrisons on the north coast of Colombia to distract enemy attention from his own inland campaign. The Irish completed their first assignment in style, landing from their ships in rough surf and charging an enemy stronghold in the seaside town of Riohacha. With the Royalists right royally routed, the Irish Legion hoisted its flag high over Riohacha’s fortress and occupied the town.

From Riohacha, General Montilla was ordered to force-march the Irish Legion southeast across the desolate Guajira Peninsula toward the Venezuelan town of Maracaibo. But Guajira Indians, armed by the Spanish, put up fierce resistance. They wiped out the advance guard in an ambush, and picked off stragglers who were searching for water. One detachment of Irish, left behind to guard the column’s rear, burned to death when Indians set fire to their huts.

Outnumbered and out manoeuvred, General Montilla ordered a retreat. No sooner had the Irish Legion reached Riohacha that they were besieged by an enemy force of 1,700. The Irish Lancers, under the command of Colonel Francis Burdett O’Connor (County Cork), provided a last minute counter-attack and saved the day. Supported by two field guns and a company of sharpshooters, O’Connor led his men in a headlong charge that sent the enemy fleeing. The feat was all the more remarkable in that the Irish Lancers, supposedly light cavalry, at this stage had not a horse among them.

Delighted with O’Connor’s bravery, General Montilla ordered another advance, declaring that his Irishmen could overwhelm even the largest royalist force. But Montilla’s caution soon overcame his confidence: at the first sign of resistance, he again signalled a retreat. The general’s prudence frustrated the headstrong Irish, still nursing grievances over lack of pay and shortages of water.

Discontent now turned to open mutiny in the ranks. Refusing to take orders from General Montilla, many demanded to be returned to Ireland. When Montilla tried to starve them into submission discipline collapsed; the soldiers ransacked towns and villages, looting valuables and drinking all the alcohol they could find. Fires broke out. And, before they could be extinguished, the power magazine in the fort blew up … and the town burned to the ground.

Although other, non-Irish soldiers were also involved in the incident, General Montilla blamed all the destruction on the Irish Legion. Furious, he ordered the mutineers expelled to the British colony of Jamaica. “The soldiers,” wrote the general, “have combined dishonour with barbarity, for they requited the friendship and kindness of the inhabitants of Riohacha by setting fire to the town.”

Montilla’s assessment was by no means unanimous. Colonel O’Connor, whose Irish Lancers remained loyal, acknowledged that the mutineers’ complaints - if not their behaviour - were perfectly justified. Another contemporary observer laid the blame on Montilla’s timid brand of leadership, as well as his inexperience in managing “such turbulent spirits” as the Irish.

Captain Charles Brown in his ‘Narrative of the Expedition to South America’ (London, 1819) says of General Montilla, “he is a man of considerable talent … but is false and intriguing, and very little respected.” General Montilla had no love for his Irish Legion and treated them harshly.

Naturally the general had the last word, and O’Connor’s men had the thankless task of disarming their compatriots and loading them onto transport ships at bayonet-point. On the 4th of June 1820, some 300 ‘mutineers’ sailed for Jamaica.

Was it a last laugh or a cruel cynicism of the

times? General Mariano Montillo got in touch

with the British Colonial government in

Jamaica and sold 300 mutineers into the virtual

slavery of the British Army. The deal was cast

on the 4th of June 1820, and General Montillo, himself,

pocketed the proceeds!

Although the ‘mutiny’ at Riohacha marked the end of the Irish Legion as an integral unit, many Irish soldiers went on to distinguish themselves in Bolivar’s service. Foremost among them was Colonel Francis Burdett O’Connor.

Colonel O’Connor’s Irish Lancers, reformed after the fighting at Riocacha and the sale of the ‘mutineers’ to the British Army in Jamaica, were finally given horses and rode to successfully besiege the ports of Cartagena and Santa Marta. The Irish Lancers repulsed a royalist counterattack on General Montilla’s headquarters at Cartagena, and were in the thick of bloody fighting at Santa Marta that left 690 royalists dead. Afterwards, Colonel O’Connor personally accepted the surrender of the city.

After the Liberation of Colombia, Colonel Francis Burdett O’Connor and his Irish Lancers went south to participate in the Peruvian campaign of General Antonio Jose de Sucre. As General Sucre’s chief of staff, this Irish officer set the strategy for the battle of Ayacucho, which was the death knell for Spanish rule in South America. In recognition of his gallantry at Ayacucho and his distinguished service on the staff, O’Connor was promoted to the rank of General.

In was in Peru, that O’Connor’s Irish Lancers met their end. The regiment, 170 strong when it charged at Riohacha, could muster fewer than 100 at the end of the Colombian campaign. By 1824, death and disease had reduced the unit to one enlisted man. This sole survivor, a young trumpeter named Patrick, was stricken with a fatal fever in the Peruvian mining village of Recuay. In his memoirs, O’Connor related how young Patrick, with the 17th of March approaching, struggled to survive until his saint’s day, and then gave up the fight.

General O’Connor, at General Sucre’s side, went on to liberate Upper Peru and establish there the new nation of Bolivia. General O’Connor became a Bolivian citizen, and after the war of Independence he became Minister of War in Bolivia, under General Santa Cruz’s presidency – and later became Governor of Tarija, a post which he held for many years. He was a man of aristocratic tastes and traditions, distinguished manners and inflexible integrity. He claimed direct descent from Roderic O’Conor Don, the last High King of Ireland (1180 A.D.) General O’Connor never returned to Ireland, he lived out his life as a gentleman farmer and family man in his adopted nation, dying at his estancia in 1870. A wartime friend once suggested that O’Connor invest his money in England. “The English,” retorted O'Connor, “forced my father off the family farm in Ireland. So I will keep my savings safely in Bolivia.”

O’Connor had come to South America as an ensign in the Irish Legion. He was made a lieutenant of the ‘Albion’ regiment, and fought all through the campaigns of Venezuela and Colombia between 1819 to 1824. He won a promotion on every battle field until his regiment was reduced to a handful of men. He then raised a regiment at his own expense and arrived in Peru in command of it, with the rank of Colonel.

Just three years previously had seen the decisive battle on the plains of Carabobo (1821), where many Irish lives were sacrificed for Venezuela’s liberation. During this critical battle the misnomered ‘British’ Battalion saw Spanish royalist forces had Bolivar’s cavalry pinned down, and with typical Irish impetuosity they took the initiative to rout the royalist forces and save the day for Bolivar … but there was a bloody ‘butcher’s bill’ and heavy Irish casualties.

In their supreme sacrifice for Venezuela, the so-called ‘British’ Legion lost all of its Irish officers killed or severely wounded and, led by an Irish Sergeant, they captured the city of Carabobo for Bolivar’s patriot forces. Honouring the dead and wounded, Simon Bolivar re-named the ‘British’ Legion ‘The Carabobo Batallion’ and conceded it the exclusive and perpetual privilege to parade with bayonets fixed.

The Irish volunteers had a huge impact of Simon Bolivar and he respected them deeply - indeed one of them, Lieutenant-Colonel William Ferguson from County Antrim, died defending Bolivar. While still in his twentieth-nine year, William Ferguson was on duty at Bogotá as aide-de-camp to General Bolívar when a plot was hatched against the General. On the 28th of September 1828 William was shot and mortally wounded. He had been engaged to the daughter of José Manuel Tatis of Cartagena, treasurer in Bolívar's army. After his death the people of Bogotá honoured William Ferguson with a State funeral and buried his remains in the city’s cathedral, and erected a handsome monument which bears a grateful inscription to ‘Colonel Guillermo Fergusson’.

Bolivar appointed a Dr. Thomas Foley (from County Kerry) as Inspector General of his Military Hospitals.

Daniel Florence O’Leary from County Cork won Bolivar’s highest esteem. After observing the young Cork man in action, Bolivar made O’Leary his personal aide-de-camp. As a member of Bolivar’s headquarters, O’Leary attained the rank of brigadier general and played a key role in plotting political and military strategy. O’Leary’s keen historical instincts, combined with his meticulous collection of war documents, has earned this Irishman a place of honour in Latin America’s history. His memoirs, published in Caracas by his son, Simon Bolivar O’Leary, fill 32 volumes. This extraordinary compilation of eyewitness accounts, correspondence and documents has proved an indispensable resource for every subsequent biographer and historian of the South American Independence period. In Colombia, where O’Leary died in 1854, a bust of the Irish hero overlooks a plaza in Bogotá. In 1882, the Venezuelan government removed O’Leary’s remains to its own capital, Caracas. There, with the highest public honours, this Irish soldier was laid to rest in the National Pantheon, the sacred burial place of Bolivar himself.

Another notable Irishman in the service of Bolivar was Arthur Sandes. Arthur was born in 1793 in County Kerry and fought as a British officer at the Battle of Waterloo. He left the British army in 1815 and two years later joined the forces of Simon Bolivar. Initially Arthur commanded the Irish ‘Black Rifles’ Battalion in the South American wars of independence. And, after achieving great distinction during the critical battle of Ayacucho, Colonel Sandes was promoted to Brigadier General. Arthur was then appointed as second-in-command of a patriot division, which also included his famous Irish ‘Black Rifles’ amongst that division’s fighting units. Following the end of the war of independence, Lima overthrew its pro-Bolivarian government and got rid of Bolivia’s military garrison. Arthur was immediately appointed as Commandant General of the port of Guayaquil (December 1827). During 1828 Arthur fought for Columbia in the war against Peru. After organising Guayaquil’s harbour defences, he led one of the two Colombian divisions at the battle of Portete de Tarqui (27th of February 1829). This Colombian victory decided the outcome of the war between Columbia and Peru. With peace restored, Arthur was appointed Governor of the Department of Azuay and settled in Cuenca. He died in this city on the 6th of September 1832 and was buried in a Carmelite convent. With regard to his personal life, O’Connor mentioned in his journals that Arthur Sandes and General Sucre both coveted the hand of the daughter of the Marquis of Solanda, a beautiful young lady from Quito. With characteristic chivalry, the Venezuelan General declined to use his more senior rank to press his advantage over the Irishman (Arthur was still only a colonel at that time). These two gentlemen agreed the winner of a card game would propose to the girl, the loser would withdraw from the race. General Sucre won and married his sweetheart, but marital bliss proved fleeting: as the Marshal of Ayacucho was assassinated in Berruecos in 1830. Arthur never married, but some of his descendants were said to have been living in Venezuela as recently as 1911 (this is not necessarily a contradiction!). Ecuador still remembers her adopted Irish son. There is an Avenida Sandes in Cuenca and the Irishman’s name is engraved on the monument at Portete de Tarqui.

Throughout South America’s liberation history you’ll find more records of the Irish than the Brits … 1,000 men of the IRISH LEGION landed on Margarita Island in Venezuela in August 1819. And 2,100 more Irish soldiers reached Venezuela in organized Irish regiments during the next years. A further 12,000 were to follow in their footsteps to secure liberty for South America from brutal Spanish colonialism. In addition, the rosters of so-called ‘British’ units in Simon Bolivar’s liberation army were also studded with such names as Murphy, Larkin, Egan, Casey, Lanagan, Doyle and McCarthy, testifying to the presence of hundreds of additional Irish troops.

A modern travesty of history is that the so-called ‘BRITISH Legion’ which is honoured in Venezuela at each year’s Anniversary of the Battle of Carabobo (24 June 1821), was in fact mostly IRISH !

proportion of the anglophones were IRISH.

Britain's then colonial connection with the

Emerald Isle has unfortunately perpetuated the

‘British’ misnomer, and dogged historical fact.

General Baron Auguste de Colbert de Chabanais (1805) Only 32 years old at the time of his death, he had a lngthy military service record and was already considered by the French as a ‘legendary’ cavalry commander.

from the Rifle Brigade Chronicle of 1914, Harold Payne’s illustration of Tom Plunket shooting General Colbert at Cacabelos on the 3rd of January 1809

A Baker Rifle with the 24-inch sword bayonet