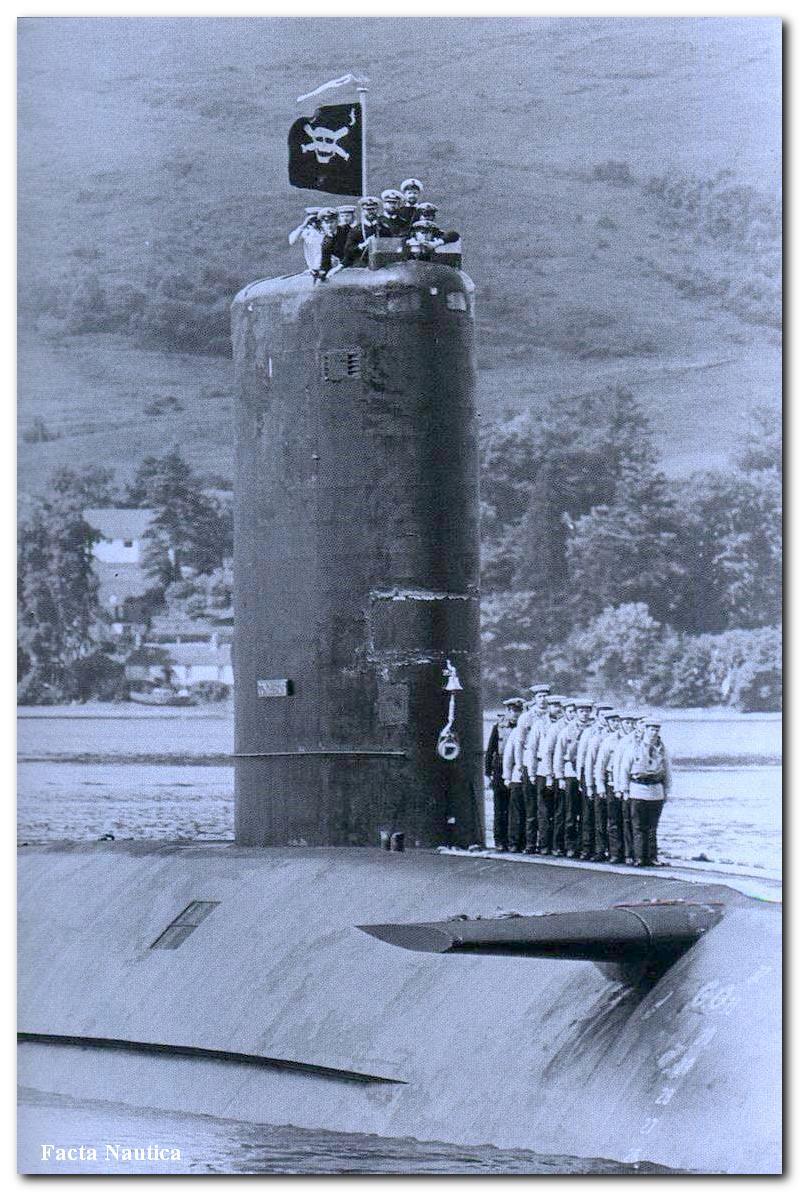

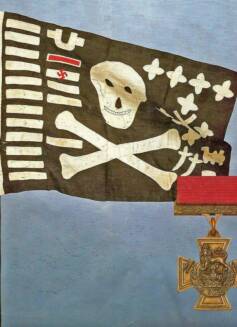

A ‘Jolly Roger’ flag, but defaced by a number of varying symbols dependent upon the type of action and used unofficially by the submarine service of the British Royal Navy to signify that the boat flying it had engaged an enemy.

It should be further noted that a torpedo attack which resulted in an enemy vessel being sunk was symbolized by a bar or torpedo, with the number of successful attacks matched by the number of symbols. A successful gun engagement was shown by a pair of cross cannons and an enemy plane downed by the silhouette of an aircraft, with each occurrence being represented by a star. Assistance in a clandestine operation (the landing of agents or commandos) was marked by the display of a dagger, with any further such operations calling for either stars or more daggers.

I've come across a fuller list of these defacements, that I copied down from the displays at the RN Submarine Museum at Gosport a few years ago:

• red bar: enemy surface vessel sunk

red bar: enemy surface vessel sunk

• red bar with a U superimposed: enemy submarine sunk

red bar with a U superimposed: enemy submarine sunk

• white bar: enemy merchant vessel sunk

white bar: enemy merchant vessel sunk

• yellow bar: Japanese merchant vessel sunk

yellow bar: Japanese merchant vessel sunk

• crossed guns and a star: enemy vessel sunk by gunfire

crossed guns and a star: enemy vessel sunk by gunfire

• a chevron: small enemy vessel sunk by gunfire

a chevron: small enemy vessel sunk by gunfire

• a chamber pot or a Chinese junk: very small enemy vessel sunk by gunfire

a chamber pot or a Chinese junk: very small enemy vessel sunk by gunfire

• a lighthouse and torch: participation in an amphibious operation (the torch on its own is often used for participation of Operation 'Torch', the landings in North Africa in 1942)

a lighthouse and torch: participation in an amphibious operation (the torch on its own is often used for participation of Operation 'Torch', the landings in North Africa in 1942)

• a lifebelt: air-sea rescue operation

a lifebelt: air-sea rescue operation

• a dagger, sword or 'The Saint' stick figure (from the novels of Leslie Charteris): landing agents or commandos ('cloak and dagger' operations in the slang of the time)

a dagger, sword or 'The Saint' stick figure (from the novels of Leslie Charteris): landing agents or commandos ('cloak and dagger' operations in the slang of the time)

• a 'jeep' (character in Popeye cartoons): chariot recovery (a 'chariot' was a one- or two-man submersible, used for raids on the shipping in enemy harbours)

a 'jeep' (character in Popeye cartoons): chariot recovery (a 'chariot' was a one- or two-man submersible, used for raids on the shipping in enemy harbours)

• a railway engine: train or track destroyed

a railway engine: train or track destroyed

• a demolition charge: ship sunk (the difference between this and the bars above for sunken vessels was not made clear)

a demolition charge: ship sunk (the difference between this and the bars above for sunken vessels was not made clear)

• diver's helmet: going below safe diving depth

diver's helmet: going below safe diving depth

• a tin opener: used by HM S/M Proteus after an Italian torpedo boat passing overhead collided with the submarine, and ripped open the submarine's ballast tanks

a tin opener: used by HM S/M Proteus after an Italian torpedo boat passing overhead collided with the submarine, and ripped open the submarine's ballast tanks

• a mine: mine-laying operations

a mine: mine-laying operations

• a cross patee: supply runs to Malta during the siege of 1942

a cross patee: supply runs to Malta during the siege of 1942

• an aircraft: enemy aircraft shot down

an aircraft: enemy aircraft shot down

• a red flower: minefield reconnaissance

a red flower: minefield reconnaissance

The Noble Society of Celts, is an hereditary society of persons with Celtic roots and

interests, who are of noble title and gentle birth, and who

have come together in a search for, and celebration of, things Celtic.

"Spring Edition 2010"

'Mick' Mannock

The First World War 'Ace of Aces'

Major Edward ‘Mick’ Mannock was an Irish member of Britain’s Royal Flying Corps, and was the highest-scoring British ace … he is still regarded as one of the greatest fighter pilots of the First World War.

It is a little known fact that, during the First World War (1914-18), thirty-eight of Britain’s Royal Flying Corps’ top ‘fighter aces’ were Irish. (But then the English are not big on praise for the Irish.) Yet the names of Standish Conn O’Grady, Paddy Langan-Byrne, Joe Callaghan, Eddy Hartigan, Cochran Patrick, have come to mean nothing to quietly anti-Irish Britain … and these heroes were also quickly forgotten in an Ireland that was desperately fighting for its independence, immediately after the end of the First World War.

Britain’s top fighter ‘ace’, with 73 enemy aircraft destroyed, was Major ‘Mick’ Mannock, who was killed in action near Lillers in France, on the 26th of July 1918. At thirty-one years of age, he was the recipient of the Victoria Cross (VC), the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) – three times !!! – and the Military Cross (MC) – twice !! … but, he was considered ‘old’ for a fighter pilot.

‘Mick’ has been claimed as ‘English’ and his birthplace is often given as the military barracks in Aldershot. He has been mythologised and demonised and even ignored.

One biographer, admitting that ‘Mick’ was born in Ireland, summed him up in these words: “As a working class, rough socialist, he was unsuitable for exploitation by the English propaganda machine, and his staunch support for continued political union with Britain made his memory unsuitable for celebration in Republican Ireland. The truth must not be forgotten; yes, he was an obsessive racist man of hate, but he was also a loyal, committed leader who loved and was loved by his many friends.” This is an unfair summary of a very complex personality. He was not a unionist and his ‘racism’ was reserved for enemies met in combat and shaped by his experiences both as a prisoner as well as in action.

‘Mick’ Mannock was born in Ballincollig, County Cork, on the 24th of May 1887, of Catholic parents. His father, also Edward, was a corporal in the British army, who was a hard-drinking man with a selfish streak, who was to abandon his wife and children when ‘Mick’ was only twelve years old.

Julia O’Sullivan married Edward Mannock in Cork. ‘Mick’ was the youngest of three … he had a sister Jess’ and a brother Patrick. The family initially followed their husband and father to army postings at The Curragh (County Kildare) and in Dublin. And, during a stay in India, where his father was serving at the time, ‘Mick’, then ten years old, suffered an amoebic infestation which caused temporarily blindness.

After being abandoned, Mrs. Mannock took her family to Wellingborough, Northamptonshire (England). At the age of twelve young ‘Mick’ was able to secure a job with the Post Office.

It is not known how he managed to educate himself, but by 1911 he was working in the engineering department of the Post Office in Wellingborough. He had become a convinced socialist and an active member of the Independent Labour Party (ILP). By the age of twenty, he had been elected secretary of the Wellingborough ILP.

Contrary to some of the stories later put out about him, ‘Mick’ was proud of his Irish ancestry and was a staunch supporter of the movement for Irish self-government. He took the ILP’s line at the time that this was best in the form of ‘Home Rule’.

In February 1914, ‘Mick’ was in Istanbul (Turkey), laying telephone cables. On the 2nd of November 1914, when Turkey allied itself with Germany and entered the war against the Allies, ‘Mick’ was interned by the Turks. He was badly treated and the experience became the triggering point of his hatred of the Turks, the Germans and all their allies.

In ill health, the Turks believed him to be dying; and so ‘Mick’ was repatriated to Britain in an exchange of prisoners during 1915.

As soon as ‘Mick’ arrived back home he joined the British Army’s Royal Army Medical Corps. He was soon promoted to the rank of sergeant-major, but his health was poor and the army considered him unfit for military duties. His determination caused him to regain his health. In 1916 he secured a commission as a second-lieutenant in the Royal Engineers signals section (communications), at Stratford. This implies that his self-education had been of a good standard in the class-ridden British army of the day.

During the summer of 1916, ‘Mick’ began reading in the newspapers about the exploits of Albert Ball, Britain’s leading flying ace. Ball, who was not yet twenty years old, had already shot down eleven German aircraft. ‘Mick’ asked for a transfer to the RFC (Royal Flying Corps) and, in August 1916, he was sent to the School of Military Aeronautics at Reading.

In February 1917, he joined the Joyce Green Reserve Squadron for flying training.

The weakness in his eye was later mythologised so that the legend of the ‘one-eyed air ace’ was born. ‘Mick’s medical records show that this was without foundation. During his first solo in an Airco DH2 ‘pusher’ biplane, he got into a spin at 1,000 feet, and recovered, but got in trouble with his commanding officer, Major Keith Caldwell … who suspected ‘Mick’ of showing-off.

Caldwell described ‘Mick’ as “very reserved, inclined towards a strong temper, but very patient and somewhat difficult to arouse.”

‘Mick’ had a natural aptitude for flying. Captain Chapman, one of the men responsible for training ‘Mick’, later reported that: “He made his first solo flight with but a few hours' instruction, for he seemed to master the rudiments of flying with his first hour in the air and from then on threw the machine about how he pleased.” Captain James McCudden, who was later to become one of Britain's leading flying aces, was another instructor who was impressed with ‘Mick’ Mannock’s skills as a pilot.

On the 31st of March 1917, ‘Mick’ was sent to join the RFC’s Nieuport-equipped 40 Squadron on the western front. He arrived at St. Omer in France on the 6th of April 1917.

At 40 Squadron, the reserved, working-class manner of ‘Mick’ did not fit in with the well-heeled upper-middle-class, ex-boarding school ‘types’ who made up the majority of his comrades. On his first night, he inadvertently sat down in an empty chair, a chair which a newly fallen flier had occupied until that day. At first ‘Mick’s personality and political opinions upset the other pilots. One of his new comrades, lieutenant Blaxland, wrote: “He seemed a boorish know-all and we all felt that the quicker he got amongst the Huns, the better that would show him how little he knew.”

Soon after arriving in France, ‘Mick’ heard the news that Albert Ball, the man whose example had inspired him to join the RFC (Royal Flying Corps), had been shot down and killed. The same day, Captain Nixon, ‘Mick’s patrol leader, was also killed during a mission to destroy German observation balloons.

Finally, on the 7th of May, he shot down a German observation balloon and thought this would gain him the acceptance of the squadron.

Lieutenant Lionel Blaxland later recalled his first impression of ‘Mick’: “He was different. His manner, speech and familiarity were not liked. New men usually took their time and listened to the more experienced hands; Mannock was the complete opposite. He offered ideas about everything: how the war was going, how it should be fought, the role of scout pilots, what was wrong or right with our machines. Most men in his position, by that I mean a man with his background, would have shut up.”

On the 17th of June ‘Mick’ shot down his first enemy aircraft. Before he could add to his total he received a wound to the head during a ‘dogfight’ with two German pilots.

‘Mick’ was sent back to England to recover. He was anxious to get back to France, and desperately short of trained pilots, the RFC agreed that ‘Mick’ could return to duty.

After returning to France in July, ‘Mick’ quickly developed a reputation as one of the most talented pilots in the RFC. In the first two weeks after arriving back at the Western Front he won four dogfights in his SE-5a. This gave him new confidence and on the 16th of August he shot down four aircraft in a day. The following morning he added two more victories to his total.

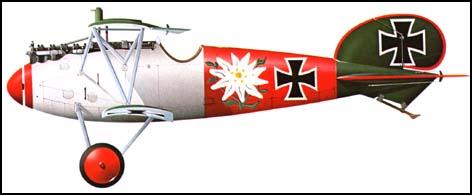

Nieuport Fighters of 40 Squadron, R.F.C.

Royal Aircraft Factory SE-5

On the 22nd of July 1917, ‘Mick’ was promoted to captain. Given command of ‘A’ Flight in 40 Squadron, one of ‘Mick’s pilots was another Irish air ace, George McElroy DFC & MC (Distinguished Flying Cross and Military Cross), who came from the Donnybrook area on the south side of Dublin. George had transferred to the R.F.C. from the Royal Irish Regiment.

McElroy, having been accredited with the destruction of 46 enemy aircraft, was later to be shot down and killed just a few days after ‘Mick’s death in action.

As flight commander, ‘Mick’ was able to introduce a new approach to combat flying. He believed that the “days of the lone fighter was past and air fighting was now a matter for co-ordinated and planned fighting units which could inflict maximum damage and minimum losses.”

Captain W. E. Johns, an RFC pilot who was later to become the famous author and creator of the immortal air-pilot character ‘Biggles’, wrote the following about ‘Mick’: “Irish by birth, he displayed all the impetuosity of the Irish. He was, of course, a fearless fighter. He was also a brilliant leader and exponent of the air combat tactics of his time.”

In September ‘Mick’ won the Military Cross for driving off several enemy aircraft while destroying three German observation balloons.

‘Mick’ was deeply affected by the amount of men he was killing. In his diary, he recorded visiting the site where one of his victims had crashed near the front-line: “The journey to the trenches was rather nauseating - dead men's legs sticking through the sides with puttees and boots still on - bits of bones and skulls with the hair peeling off, and tons of equipment and clothing lying about. This sort of thing, together with the strong graveyard stench and the dead and mangled body of the pilot combined to upset me for a few days.”

Albatros D-Va

Pfalz D.III Scout

’Mick’ was especially upset when he saw one of his victims catch fire on its way to the ground. From that date on, ‘Mick’ always carried a revolver with him in his cockpit. As he told his friend Lieutenant MacLanachan: “The other fellows all laugh at me for carrying a revolver. They think I'm going to shoot down a machine with it, but they're wrong. The reason I bought it was to finish myself as soon as I see the first signs of flames.”

’Mick’s fear of fire was made worse by the British High Command’s decision not to allow pilots in the RFC to carry parachutes. ‘Mick’ believed it was unfair to deny British airman to right to have parachutes when German pilots had been using them successfully for several months. He was especially angry about the main reason given for this decision: “It is the opinion of the board that the presence of such an apparatus might impair the fighting spirit of pilots and cause them to abandon machines which might otherwise be capable of returning to base for repair.”

On the 12th of August 1917, ‘Mick’ shot down and captured Lieutenant Joachim von Bertrab of Germany’s Jasta 30. Both flyers were aces – ‘Mick’ had shot down a balloon and four airplanes; Bertrab was his sixth ‘victory’; Bertrab had shot down five airplanes and was trying to bring down a balloon for his sixth ‘victory’.

‘Mick’ kept flying and conquered his fears, working tirelessly at gunnery practice and forcing himself to get close to the German airplanes. After one kill, he coldly described it. “I was only ten yards away from him - on top so I couldn't miss. A beautifully coloured insect he was - red, blue, green, and yellow. I let him have 60 rounds, so there wasn't much left of him.”

The following month he was awarded a ‘bar’ to his Military Cross (second award).

In January 1918, ‘Mick’ had so distinguished himself that he was given 30 days leave and two months of home service away from the front. ‘Mick’ was not one to tolerate what he saw as ‘idleness’. He agitated to be returned to the combat zone.

Eventually he was put in command of 74 (Training) Squadron in London in order to prepare it for a posting to France.

It was agreed that ‘Mick’ was an excellent teacher with a sense of humour. In one celebrated episode he led his squadron in bombing a rival RFC squadron HQ with 200 oranges. They returned the compliment bombing ‘Mick’s headquarters with 200 bananas.

In February 1918, ‘Mick’ was appointed as a flight commander in the newly formed No. 74 Squadron. By April 1918, Mick led his squadron to the Front at St Omer in France. On his first patrol, he shot down another enemy aircraft but claimed the entire squadron should take the credit.

The next three months saw ‘Mick’ score thirty-six more ‘kills’. ‘Mick’ had now overtaken Albert Ball’s total of forty-four ‘kills’ and, on the 20th of July, he shot down an Albatros giving him fifty-eight victories, which was one more ‘kill’ than the British record held by fellow Irishman, James McCudden.

Van Ira, a South African flier in 74 Squadron commented on ‘Mick’s success: “Four in one day! What is the secret? Undoubtedly the gift of accurate shooting, combined with the determination to get to close quarters before firing. It's an amazing gift, for no pilot in France goes nearer to a Hun before firing than (Caldwell), but he only gets one down here and there, in spite of the fact that his tracer bullets appear to be going through his opponent's body.” ‘Mick’ was awarded the DSO (Distinguished Service Order) in May 1918. And, not long after his four-in-a-day feat, the award of a ‘bar’ to his DSO (second award) just two weeks later.

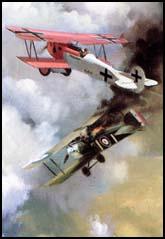

‘Dogfight’ by Joseph A. Phelan (Irish war artist)

Nonetheless, ‘Mick’ was deeply affected by the number of men he was killing. In his diary, he recorded visiting the site where one of his victims had crashed near the front-line: “The journey to the trenches was rather nauseating - dead men’s legs sticking through the sides with puttees and boots still on - bits of bones and skulls with the hair peeling off, and tons of equipment and clothing lying about. This sort of thing, together with the strong graveyard stench and the dead and mangled body of the pilot combined to upset me for a few days.”

By this time, the strain of combat flying and the fear of his own fiery death got to ‘Mick’. But he kept flying, repeatedly scoring multiple kills. He fell sick with influenza, aggravated by tension.

By June 1918, he had earned a ‘home leave’. He was promoted to the rank of Major and sent back to England. The strain of combat flying, tension, aggravated by ‘flu’ did not help, but he refused to rest. Reluctantly, his superiors gave him command of 85 Squadron.

Life expectancy was short for fighter pilots in 1918. His friends were being killed every day. On the 9th of July 1918, ‘Mick’ heard that another Irish friend, James McCudden, had been shot down and killed. Major McCudden was only 22 years old.

Like ‘Mick’, James’ father had also been an Irish non-commissioned officer. However, McCudden had been born in Kent (England) … but, like ‘Mick’, he considered himself to be Irish. James was the recipient of the VC, DSO, MC, and the MM (Military Medal) - plus the Croix de Guerre (France). He had accounted for 51 enemy aircraft.

James McCudden’s young brother, lieutenant ‘Jack’ McCudden MC of 84 Squadron had been shot down and killed on the 18th of March 1918. He was 21 years old at the time, and had accounted for eight enemy aircraft before he met his end.

‘Mick’ went on a week of ‘rampage’ and destruction. He wrote in his last letter home: “I feel that life is not worth hanging on to - had hopes of getting married but ...” The death of McCudden certainly had a profound affect on him. Ruthlessness took hold of him. He told one friend after machine-gunning the crew of a German aircraft having forced it to crash: “The swine are better dead - no prisoners.” At the same time, a conviction of his own forthcoming death seized him. On starting his third tour of duty in July, as CO of 85 Squadron, ‘Mick’confided his mortal fears to a friend, worried that three was an unlucky number. He became obsessed with neatness and order; his hair, his medals, his boots, everything had to be ‘just so.’ When he shot down an aircraft on the 22nd of July, a friend congratulated him. “They'll have the red carpet out for you after the war, Mick.” But ‘Mick’ glumly replied, “There won't be any 'after the war' for me.”

On 26 July, ‘Mick’ offered to help a new arrival, an Irish-New Zealander, Lt. D.C. Inglis, obtain his first kill on a routine patrol. And, after shooting down an enemy LVG two-seater behind the German front-line, the two men headed for home.

While crossing the trenches, the fighters were met with a massive volley of ground-fire. The engine of ‘Mick’s aircraft was hit and immediately caught fire and crashed behind German lines. ‘Mick’s body was found 250 yards from the wreck of his machine. He did not fire his revolver but it is believed he might have jumped from his blazing plane just before it crashed (in an attempt to survive the crash).

Inglis described what happened: “Falling in behind ‘Mick’ again we made a couple of circles around the burning wreck and then made for home. I saw ‘Mick’ start to kick his rudder, then I saw a flame come out of his machine; it grew bigger and bigger. ‘Mick’ was no longer kicking his rudder. His nose dropped slightly and he went into a slow right-hand turn, and hit the ground in a burst of flame.”

“I circled at about twenty feet but could not see him, and as things were getting hot, made for home and managed to reach our outposts with a punctured fuel tank. Poor Mick ... the bloody bastards had shot my major down in flames.”

Did ‘Mick’ suffer the flaming death that he had long feared or did he use his pistol? Who had shot him down? The combat reports and consensus agreed it was a lucky burst of anti-aircraft fire.

The exact cause of ‘Mick’s death remains uncertain. A year later, after intensive lobbying by Ira Jones and many of ‘Mick’s former comrades, he was awarded the Victoria Cross. ‘Mick’, in spite of the war, had not ceased to advocate socialism. He had an abiding faith that the Labour Party in Britain would secure its promise of social justice for everyone and help Ireland to achieve self-government.

Certainly, ‘Mick’s name was conjured in Britain by the Labour Party in the December 1918, general election … and his biographer, Dr Adrian Smith, believed that ‘Mick’s time as secretary of the Wellingborough ILP led to a specific gain of a local Labour seat in that election.

Unfortunately the Northamptonshire Labour Club seems to have lost all its archives although there is a civil commemoration for ‘Mick’ there as well as the annual commemoration (curiously) in the Anglican Canterbury Cathedral.

It was not until the 1930s that certain members of the Labour Party began to foster myths about a ‘Mick’, the myth of a ‘lost Labour leader’, and play up his ruthless attitude to waging war as a warning against appeasement of Nazi Germany.

Dr Adrian Smith, of the University of Southampton, in his book Mick Mannock, Fighter Pilot: Myth, Life and Politics has pointed out that it is ironic that Mannock was built up as the English ‘ace of aces’. All his comrades and contemporaries knew ‘Mick’ had pride in his Irish ancestry and knew of his staunch advocating of self-government for Ireland.

However, even with an understanding of his personal experiences as the source of ‘Mick’s hatred of his enemies, one does wonder how he reconciled his previous pre-war socialist international proletarian solidarity with that later ruthlessness. Probably it was simply war that changed him.

Today, ‘Mick’ Mannock has been mythologised as an archetypal ‘English hero’ in countless novels, films and plays, as either himself or in thinly disguised form. His socialism and his Irish nationalism are just conveniently forgotten by the English.

‘Mick’ is commemorated on the Royal Flying Corps Memorial to the Missing at the Faubourg d’Amiens Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetery in Arras (France). There is also a memorial plaque in honour of ‘Mick’ in Canterbury Cathedral. ‘Mick’ Mannock’s name is listed on the Wellingborough War Memorial with the other fallen men from the town and the local Air Training Corps unit bears his name - 378 (Mannock) Squadron.

On the 26th of July 2008, a wreath was laid in Wellingborough to mark the 90th anniversary of his death. In addition, officers and cadets of 378 (Mannock) Squadron laid a wreath at the Arras War Memorial.

‘Mick’ is regarded as the leading British ace during the First World War and is often claimed to be the ‘ace of aces’ of the British Empire, claiming 73 victories, seven behind the leading pilot of the war, Baron Manfred von Richthofen, and one ahead of Canadian ace Billy Bishop.

Military Cross citation:

“For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. In the course of many combats he has driven off a large number of enemy machines, and has forced down three balloons, showing a very fine offensive spirit and great fearlessness in attacking the enemy at close range and low altitudes under heavy fire from the ground.” MC citation, Supplement to the London Gazette, 17 September 1917

Victoria Cross citation:

“On the 17th June, 1918, he attacked a Halberstadt machine near Armentières and destroyed it from a height of 8,000 feet (2,400 m). On the 7th July, 1918, near Doulieu, he attacked and destroyed one Fokker (red-bodied) machine, which went vertically into the ground from a height of 1,500 feet (460 m). Shortly afterwards he ascended 1,000 feet (300 m) and attacked another Fokker biplane, firing 60 rounds into it, which produced an immediate spin, resulting, it is believed, in a crash. On the 14th July, 1918, near Merville, he attacked and crashed a Fokker from 7,000 feet (2,100 m), and brought a two-seater down damaged. On the 19th July, 1918, near Merville, he fired 80 rounds into an Albatross two-seater, which went to the ground in flames. On the 20th July, 1918, East of La Bassée, he attacked and crashed an enemy two-seater from a height of 10,000 feet (3,000 m). About an hour afterwards he attacked at 8,000 feet (2,400 m) a Fokker biplane near Steenwercke and drove it down out of control, emitting smoke. On the 22nd July, 1918, near Armentières, he destroyed an enemy triplane from a height of 10,000 feet (3,000 m). Major Mannock was awarded the undermentioned distinctions for his previous combats in the air in France and Flanders: Military Cross, gazetted 17th Sept., 1917; Bar to Military Cross, gazetted 18th Oct., 1917; Distinguished Service Order, gazetted 16th Sept., 1918; Bar to Distinguished Service Order (1st), gazetted 16th Sept., 1918; Bar to Distinguished Service Order (2nd), gazetted 3rd Aug., 1918. This highly distinguished officer during the whole of his career in the Royal Air Force, was an outstanding example of fearless courage, remarkable skill, devotion to duty and self-sacrifice, which has never been surpassed.”

DSO Bar citation, Supplement to the London Gazette, 16 September 1918

Distinguished Service Order citation to Second Bar:

“This officer has now accounted for 48 enemy machines. His success is due to wonderful shooting and a determination to get to close quarters; to attain this he displays most skilful leadership and unfailing courage. These characteristics were markedly shown on a recent occasion when he attacked six hostile scouts, three of which he brought down. Later on the same day he attacked a two-seater, which crashed into a tree.” DSO Second Bar citation, Supplement to the London Gazette, 3 August 1918

‘Mick’s Victoria Cross was presented to his father at Buckingham Palace in July 1919. Edward Mannock (senior) was also given his son’s other medals, even though ‘Mick’ had stipulated in his will that his father should receive nothing from his estate. They have since been recovered and can be seen at the RAF Museum at Hendon.

‘Mick’ was highly regarded as a tactician, patrol leader and combat pilot and his oft-quoted cardinal rule was “Always above, seldom on the same level, never underneath,” by which he meant never engage the enemy without holding the advantage, and the greatest advantage in air fighting was height. According to ‘Mick’, tactics should be adjusted according to the situation. However the main principle remained:

“The enemy must be surprised and attacked at a disadvantage, if possible with superior numbers so the initiative was with the patrol. ... The combat must continue until the enemy has admitted his inferiority, by being shot down or running away.”

‘Mick’ formulated a set of practical rules for air fighting on the Western Front that, like Germany’s Oswald Boelcke’s Dicta, were passed on to new pilots.

1. Pilots must dive to attack with zest, and must hold their fire until they get within one hundred yards of their target.

Pilots must dive to attack with zest, and must hold their fire until they get within one hundred yards of their target.

2. Achieve surprise by approaching from the East. (From the German side of the front.)

Achieve surprise by approaching from the East. (From the German side of the front.)

3. Utilise the sun's glare and clouds to achieve surprise.

Utilise the sun's glare and clouds to achieve surprise.

4. Pilots must keep physically fit by exercise and the moderate use of stimulants.

Pilots must keep physically fit by exercise and the moderate use of stimulants.

5. Pilots must sight their guns and practise as much as possible as targets are normally fleeting.

Pilots must sight their guns and practise as much as possible as targets are normally fleeting.

6. Pilots must practise spotting machines in the air and recognising them at long range, and every aeroplane is to be treated as an enemy until it is certain it

Pilots must practise spotting machines in the air and recognising them at long range, and every aeroplane is to be treated as an enemy until it is certain it

7. Pilots must learn where the enemy's blind spots are.

Pilots must learn where the enemy's blind spots are.

8. Scouts must be attacked from above and two-seaters from beneath their tails.

Scouts must be attacked from above and two-seaters from beneath their tails.

9. Pilots must practise quick turns, as this manoeuvre is more used than any other in a fight.

Pilots must practise quick turns, as this manoeuvre is more used than any other in a fight.

10. Pilot must practise judging distances in the air as these are very deceptive.

Pilot must practise judging distances in the air as these are very deceptive.

11. Decoys must be guarded against — a single enemy is often a decoy — therefore the air above should be searched before attacking.

Decoys must be guarded against — a single enemy is often a decoy — therefore the air above should be searched before attacking.

12. If the day is sunny, machines should be turned with as little bank as possible, otherwise the sun glistening on the wings will give away their presence at a

If the day is sunny, machines should be turned with as little bank as possible, otherwise the sun glistening on the wings will give away their presence at a

13. Pilots must keep turning in a dogfight and never fly straight except when firing.

Pilots must keep turning in a dogfight and never fly straight except when firing.

14. Pilots must never, under any circumstances, dive away from an enemy, as he gives his opponent a non-deflection shot — bullets are faster than

Pilots must never, under any circumstances, dive away from an enemy, as he gives his opponent a non-deflection shot — bullets are faster than

15. Pilots must keep their eye on their watches during patrols, and on the direction and strength of the wind.

Pilots must keep their eye on their watches during patrols, and on the direction and strength of the wind.

Second World War aces, such as Douglas Bader and ‘Johnny’ Johnson, acknowledge that ‘Mick’s tactics served as inspiration to them, leading ‘Mick’ to be acknowledged as the greatest air ace of all time.

Quotes about ‘Mick’ Mannock:

(1) Jim Eyles first met ‘Mick’ Mannock when he was twenty-four. “I first met ‘Mick’ at a cricket match in Wellingborough. I was impressed with him immediately. He was a clean-cut young man, although not what one would call well dressed; in fact, he was a bit threadbare. I asked him if he would like to move in with my wife and myself, and he was most happy about the idea. After he moved in, our home was never the same again, our normally quiet life gone forever. It was wonderful really. He would talk into the early hours of the morning if you let him - all sorts of subjects: politics, society, you name it and he was interested. It was clear from the outset he was a socialist. He was also deeply patriotic. A kinder, more thoughtful man you could never meet.”

(2) Captain Chapman was one of ‘Mick’ Mannock’s teachers at the School of Military Aeronautics. He later described ‘Mick’ Mannock’s early training. “When he arrived he seemed not to have the slightest conception of an aeroplane. The first time we took off the ground, Mannock, unlike many pupils, instead of jamming the rudder and seizing the joystick in a herculean grip, looked over the side of the aeroplane at the earth, which was dropping rapidly away from him, with an expression which betrayed the mildest interest. He made his first solo flight with but a few hours' instruction, for he seemed to master the rudiments of flying with his first hour in the air and from then on threw the machine about how he pleased.”

(3) Keith Caldwell was Major ‘Mick’ Mannock’s commander in 74 Squadron during the First World War. In an interview he gave in 1981, Caldwell explained why Mannock was such a successful pilot. “Mannock was an extraordinarily good shot and a very good strategist, he could place his flight team high against the sun and lead them into a favourable position where they would have the maximum advantage. Then he would go quickly on the enemy, slowing down at the last possible moment to ensure that each of his followers got into a good firing position.”

(4) H. G. Clements of 74 Squadron wrote an account of Major ‘Mick’ Mannock in 1981. “The fact that I am still alive is due to ‘Mick’s high standard of leadership and the strict discipline on which he insisted. We were all expected to follow and cover him as far as possible during an engagement and then to rejoin the formation as soon as that engagement was over. None of ‘Mick’s pilots would have dreamed of chasing off alone after the retreating enemy or any other such foolhardy act. He moulded us into a team, and because of his skilled leadership we became a highly efficient team. Our squadron leader said that Mannock was the most skilful patrol leader in World War I, which would account for the relatively few casualties in his flight team compared with the high number of enemy aircraft destroyed.”

(5) Lieutenant MacLanachan met ‘Mick’ Mannock in May 1917. After the war MacLanachan wrote about his experiences in his book Fighter Pilot.

“Mick’ was twenty-eight or twenty-nine when I met him for the first time. He had then been two months in France. Everything about him demonstrated his vitality, a strong, manly man. His alert brain was quick, and an unbroken courage and straightforward character forced him to take action where others would sit down uncomprehending. I was awed by his personality.”

(6) Jim Eyles later recalled ‘Mick’ Mannock's last leave before his death. “I well remember his last leave. Gone was the old sparkle we knew so well; gone was the incessant wit. I could see him wringing his hands together to conceal the shaking and twitching, and then he would leave the room when it became impossible for him to control it. On one occasion we were sitting in the front talking quietly when his eyes fell to the floor, and he started to tremble violently. He cried uncontrollably. His face, when he lifted it, was a terrible sight. Later he told me that it had just been a 'bit of nerves' and that he felt better for a good cry. He was in no condition to return to France, but in those days such things were not taken into account.”

(7) An extract from ‘Mick’ Mannock’s last letter to Jim Eyles. “I feel that life is not worth hanging on to. I had hopes of getting married, but not now.”

(8) Private Naulls was in the front trenches when he saw ‘Mick’s aircraft brought down. “There was a lot of rifle-fire from the Jerry trenches, and a machine-gun near Robecq opened up, using tracers. I saw these strike Mannock’s engine. A bluish-white flame appeared and spread rapidly; smoke and flames enveloped the engine and cockpit

An Irish Airman Foresees His Death

I know that I shall meet my fate

Somewhere among the clouds above;

Those that I fight I do not hate,

Those that I guard I do not love;

My country is Kiltartan Cross,

My countrymen Kiltartan's poor,

No likely end could bring them loss

Or leave them happier than before.

Nor law, nor duty bade me fight,

Nor public men, nor cheering crowds,

A lonely impulse of delight

Drove to this tumult in the clouds;

I balanced all, brought all to mind,

The years to come seemed waste of breath,

A waste of breath the years behind

In balance with this life, this death.

Sir Anthony Miers V.C.

Scottish Submarine Hero

school teachers predicted he would either be court-martialled or earn the Victoria Cross – he did both

Described as “an explosive character”, Rear Admiral Sir Anthony Miers was fiery-tempered and prone to speaking his mind, which did little to endear him to his superior officers. However, they recognized his talent, and he made steady progress with his career in Britain’s Royal Navy.

Anthony Meirs was a World War Two hero and a very determined submarine skipper, who was awarded the Victoria Cross (the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces) as well as two Distinguished Service Orders … and was appointed as a Knight Commander of the British Empire, and made a Companion of the Order of the Bath, and promoted to Rear Admiral … but he was also a very a ‘controversial’ figure; involving two incidents that were alleged to be ‘war crimes’.

When Anthony Miers was a pupil at Wellington College, the school for "the sons of heroes", a tutor predicted that he

would either be court-martialled or earn the Victoria Cross. Anthony Miers achieved both.

For most of his life Sir Anthony was a ‘ball of fire’, one of the

British Royal Navy’s most colourful and controversial officers.

The short, stocky man with a penetrating glare was seen as

“totally loyal, outstandingly keen, fearless, hot-tempered and

incautiously spoken”. His language was ‘paint-blistering’.

Sir Anthony hated losing, whether it was on the playing field

or at sea hunting down the enemy. During the Second

World War he carried out brilliant patrols as commander of the British submarine HMS Torbay.

Anthony Cecil Capel Miers was born in Birchwood, Inverness, 11 November 1906, the son of D. N. C. C. Miers and Margaret Annie Christie. He was educated at Stubbington House, Edinburgh Academy, and Wellington College.

Anthony Miers was only seven years old when his father Douglas, a captain in the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, was killed in action in France … fewer than six weeks after the outbreak of the First World War.

Two of his uncles also died serving as army officers - one was murdered by ‘Boers’ in 1901, during the war in South Africa, and the other was fatally wounded in 1917 before the Third Battle of Ypres.

The young Anthony Miers quickly developed a remarkable mental toughness, thanks partly to his formidable mother … who lost three children. At Wellington College he developed a passion for sport, especially rugby. One naval officer would say of him: “He never became a good loser. He was fiercely competitive and determined, from his youngest years, to win - whatever and however.”

Anthony Miers joined the Royal Navy in 1925 as a special-entry cadet, aged 19. Three years later he entered the submarine service. As he rose in rank, men would dread his volcanic eruptions, which for those on the receiving end might culminate in a black eye, close arrest, or being ‘fired’. For someone really unlucky, it could be all three!

But when the ‘fire-eater’ cooled down he could be ‘charm personified’. Sir Anthony did not bear grudges; a man put under close arrest at lunchtime would probably find himself free by teatime, as if nothing had happened. And, no one who came into contact with his fists ever made a formal complaint. When he was in command Sir Anthony was fiercely loyal to his crew.

Anthony Miers served in HM Submarine M2, HM Submarine H28 and HM Submarine Rainbow, from 1931to 1936, and commanded HM Submarine L54, from 1936 to 1937. He attended the Navy Staff Course and was promoted Lieutenant-Commander in 1938. From 1939 to 1940, he served in battleships on the staff of Admiral of the Fleet Sir Charles Forbes, who was Commander-in-Chief of the Home Fleet.

It was in 1933 that he fulfilled one of his tutor’s prophecies. He was court-martialled for attempting to strike a sailor, a stoker. The incident came to light only because Sir Anthony reported himself to his commanding officer. He may have been involved in an argument with the rating over a football match, but at the hearing neither man offered an explanation.

Sir Anthony was dismissed from his ship, and a few months later he was sent to Hong Kong as first-lieutenant of the submarine HMS Rainbow. Here he acquired the lower-deck nickname ‘Gamp’ - after the Charles Dickens character ‘Mrs Gamp’ who carried a bulky umbrella. ‘Gamp’ became a common expression for an umbrella. Sir Anthony would often appear in the conning tower of Rainbow with an umbrella to ward off tropical storms.

Wellington College

British national monument to the Duke of Wellington (an Irishman) located in Berkshire, England - granted a Royal Charter in 1853 as the ‘Royal and Religious Foundation of The Wellington College’

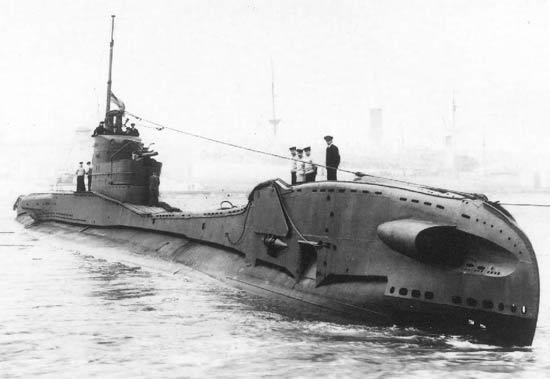

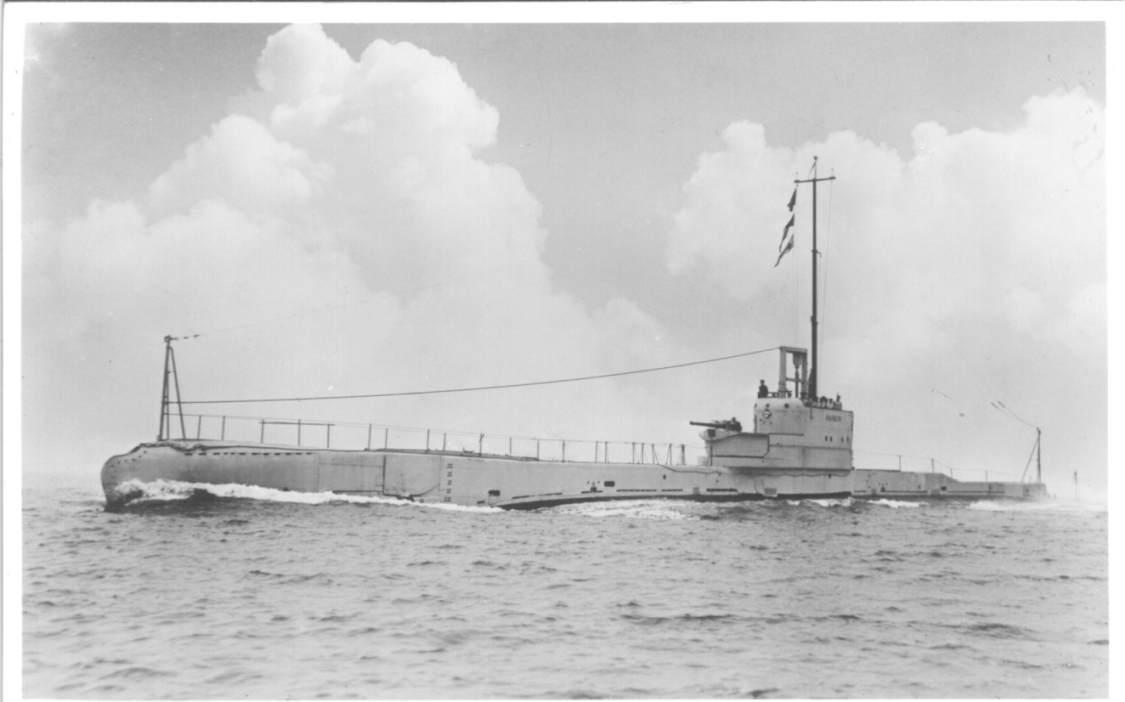

HMS Torbay

HMS Rainbow

In November 1940 he was given command of His Majesty’s Submarine Torbay. In March 1941 Torbay sailed from Portsmouth on her first offensive patrol, to intercept the German battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, which were heading for the French port of Brest after their raiding sortie in the North Atlantic.

Scharnhorst

Gneisenau

Unable to find the German warships, HMS Torbay was ordered to continue to the Gibraltar – the British fortress on the southern tip of Spain, at the Atlantic Ocean entry to the Mediterranean Sea. And, after another patrol in the Mediterranean, Torbay joined Britain’s 1st Submarine Flotilla at the Egyptian port of Alexandria.

Operating from the Egyptian port of Alexandria, HMS Torbay patrolled the Mediterranean for the next 12 months, sinking a number of ships, and taking part in several special operations.

Torbay was involved in attacks on Axis convoys on three occasions. The attack on the first convoy, on the 10th of June 1941, involved Torbay making three attack runs on an Italian convoy off the Turkish Dardanelles.

This first convoy attack failed to produce any results. Sir Anthony’s second convoy attack resulted in a torpedo hit on the Italian tanker Utilitas but the torpedo failed to explode. In his third convoy attack, the Italian tanker Giuseppina Ghirardi was torpedoed and sunk. This convoy attack took place on the 12th of August 1941, west of Benghazi, Libya.

During the third convoy attack, HMS Torbay also fired on the Italian merchant ships Bosforo and Iseo but missed both. Torbay was heavily depth charged following these attacks.

On the 5th of July 1941, HMS Torbay attacked and sunk the Italian submarine Jantina.

In November 1941 HMS Torbay was tasked with landing a party of commandos for the ill-fated ‘Operation Flipper’ (the special forces assault on the headquarters of Rommel’s Afrika Korps).

On the 4th of March 1942 in Corfu Harbour (north-western Greece), having followed an enemy convoy into the harbour the previous day, HMS Torbay fired torpedoes at a destroyer and two 5,000 ton transports … scoring hits on the two supply ships, which almost certainly sank. Torbay then had a very hazardous withdrawal to the open sea, enduring 40 depth-charges. The submarine had been in closely-patrolled enemy waters for 17 hours.

For this exploit Lieutenant Commander Anthony Miers was awarded the Victoria Cross.

However, it was Anthony’ first patrol from Alexandria in July 1941 that featured two controversial incidents which gave rise to the accusation of war crimes.

On two separate occasions, Sir Anthony ordered the machine-gunning of several shipwrecked German soldiers in rafts, who had jumped overboard when their vessels were sunk by the Torbay.

On the night of the 9th of July 1941, Sir Anthony had attacked several sailing ships carrying German troops and supplies off the island of Crete. The British submarine rose to the surface and opened fire with her four-inch gun.

Sir Anthony also made no attempt to conceal his actions, his patrol log recording: "Submarine cast off, and with the Lewis gun accounted for the soldiers in the rubber raft to prevent them from regaining their ship..."

When informed of Lieutenant-Commander Miers’ actions, the ‘Flag Officer Submarines’ (Admiral Horton wrote) to the Admiralty about the possibility of German reprisals: "As far as I am aware, the enemy has not made a habit of firing on personnel in the water or on rafts even when such personnel were members of the fighting services; since the incidents referred to in Torbay's report, the Germans may feel justified in doing so."

The Admiralty then sent a strongly worded letter to Sir Anthony advising him not to repeat the practices of his last patrol.

Nonetheless, it was that famous temper that helped him to win the Victoria Cross in March 1942. He had already carried out nine successful patrols with HMS Torbay in the Mediterranean theatre, earning the plaudit "Nazi Public Enemy Number One"

HMS Torbay entering Grand Harbour, Malta

Sir Anthony was angry. If he had not chased the other ships he would have been in an excellent position to attack this enemy convoy. He gambled that the enemy ships would anchor off Corfu harbour to pick up fuel. HMS Torbay then entered the enemy-held Corfu Channel, 30 miles long, with the island of Corfu on one side and parts of the Greek and Albanian mainland on the other.

The British submarine went to a spot opposite the harbour and then remained for a time on the moonlit surface charging her batteries.

One British sailor said later: "Small enemy boats passed to and fro, bringing back Nazi troops from the night's shore leave.

“We saw people quite clearly silhouetted in the glare of car headlamps and pushbike lights. We watched ships unloading, and heard enemy voices shouting. How the devil they never saw 260 feet of submarine lying around is a miracle."

HMS Torbay was forced to dive to avoid a patrol vessel. At dawn she moved in to attack, but was forced to turn away because of another vessel. Then their periscope showed two large supply ships, "perfect targets", at anchor. Torpedoes struck both of them. Torbay went deep, turned and headed for the southern entrance of the channel.

Search boats were joined by an enemy destroyer plus an anti-sub patrol aircraft, and 40 depth charges were dropped. A large schooner acting as a boom defence vessel tried to block the southern entrance, but Torbay escaped … after 17 hours in enemy waters.

It was hailed as one of the most remarkable submarine patrols carried out during the war.

HMS Torbay and crew

Sir Anthony’s Victoria Cross Award citation reads:

Lieutenant Commander Anthony Cecil Chapel Miers DSO Royal Navy Whilst on patrol in HM Submarine Torbay off the Greek coast on the 4th March 1942. Lieutenant Commander Miers sighted a northbound convoy of four troopships entering the South Corfu Channel and since they had been too far distant for him to attack initially, he decided to follow in the hope of catching them in Corfu Harbour. During the night 4/5 March, Torbay approached undetected up the channel and remained on the surface charging her battery. Unfortunately the convoy passed straight through the channel but on the morning of the 5th March, in glassy sea conditions, Miers successfully attacked two store ships present in the roadstead and then brought Torbay safely back to the open sea. The submarine endured 40 depth charges and had been in closely patrolled enemy waters for seventeen hours.

In the summer of 1942 Torbay returned to Britain. Anthony Miers hated losing, whether it was at rugby on the playing field or at sea hunting down the enemy. He was promoted to the rank of Commander, and appointed as submarine Staff Liaison Officer on the staff of Admiral Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief of the United States Pacific Fleet, from 1943 to 1944.

From 1944 to 1945, Sir Anthony commanded Britain’s 8th Submarine Flotilla at HMS Maidstone.

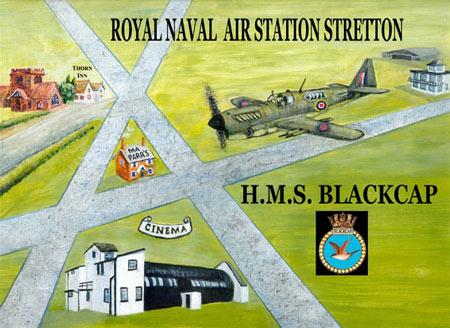

He married Patricia Mary Millar in 1945, with whom he had one son and one daughter and in 1946, he was promoted to the rank of naval Captain, and from 1948 to 1950 he commanded HMS Blackcap, the Royal Naval Air Station at Stretton.

From 1950 to 1952 he commanded HMS Forth and Britain’s 1st Submarine Flotilla.

He was on the staff of the Royal Naval College at Greenwich from 1952 to 1954

From 1954 to 1955, he commanded the aircraft carrier HMS Theseus.

Royal Naval College at Greenwich

HMS Forth & 1st Submarine Flotilla

HMS Theseus & Fairie Firefly aircraft

Hard landing by a Hawker Seafury

His Victoria Cross is displayed at the Imperial War Museum in London (England)

He was promoted to the rank of Rear-Admiral in 1956, and appointed Flag Officer, Middle East from 1956 to 1959.

Sir Anthony retired from the Royal Navy in 1962 and worked for Mills and Allen Ltd, until 1974; as well as the London Provincial Poster Group until 1983; and as Director for Development Co-ordination of National Car Parks, from 1971.

He died in 1985 and is buried at Tomnahurich Cemetery, Inverness, Scotland … in the Roman Catholic Section.

During the Second World War HMS Torbay attacked and sank the following ships:-

• The Italian submarine Jantina

The Italian submarine Jantina

• The German auxiliary submarine chaser 13 V 2 / Delpa II

The German auxiliary submarine chaser 13 V 2 / Delpa II

• The Italian auxiliary patrol vessels R 113 / Avanguardista, V 90/San Girolamo and V 276 / Baicin

The Italian auxiliary patrol vessels R 113 / Avanguardista, V 90/San Girolamo and V 276 / Baicin

• The German army cargo ship Bellona

The German army cargo ship Bellona

• The German troopship Kari (the former French Ste. Colette, in turn the former Norwegian Kari)

The German troopship Kari (the former French Ste. Colette, in turn the former Norwegian Kari)

• The German troop transport Palma (the former Italian Polcevera)

The German troop transport Palma (the former Italian Polcevera)

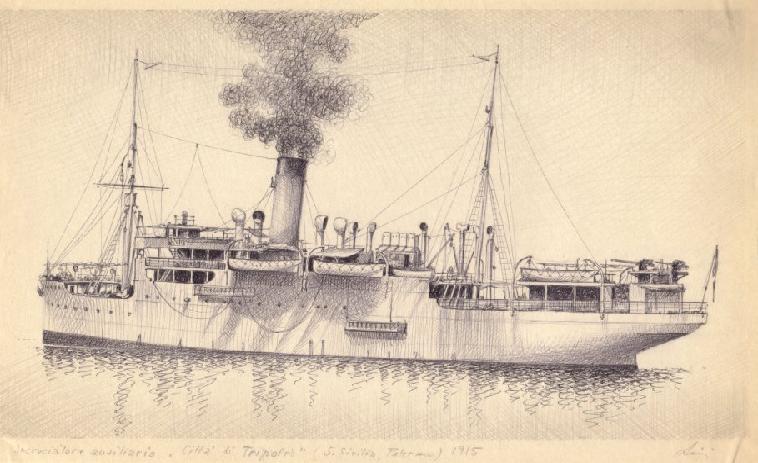

• The Italian merchants Citta di Tripoli, Ischia, Maddalena G. and Lido

The Italian merchants Citta di Tripoli, Ischia, Maddalena G. and Lido

• The Italian ship Aderno (the former British Ardeola)

The Italian ship Aderno (the former British Ardeola)

• The Danish merchant Grete

The Danish merchant Grete

• The French merchant Lillios

The French merchant Lillios

• The Spanish merchant Juan de Astigarraga and the French merchant Oasis (Both ships were under German control)

The Spanish merchant Juan de Astigarraga and the French merchant Oasis (Both ships were under German control)

• A German floating dock

A German floating dock

• The small Italian merchants Versilia and Tarquinia

The small Italian merchants Versilia and Tarquinia

• A Greek fishing vessel

A Greek fishing vessel

• The Italian fishing vessel Madonna di Porto Salvo

The Italian fishing vessel Madonna di Porto Salvo

• Seven German sailing vessels, including the L XIV, L I, L XII, L V and the L VI

Seven German sailing vessels, including the L XIV, L I, L XII, L V and the L VI

• The Italian sailing vessels Gesu E Maria, Pozzalo, Columbo, Gesu Giuseppe E Maria and Gesu Crocifisso

The Italian sailing vessels Gesu E Maria, Pozzalo, Columbo, Gesu Giuseppe E Maria and Gesu Crocifisso

• Twelve Greek sailing vessels, including the Sofia and the P III

Twelve Greek sailing vessels, including the Sofia and the P III

• The sailing vessel Evangelista

The sailing vessel Evangelista

• Two unknown sailing vessels

Two unknown sailing vessels

HMS Torbay also damaged the following ships:-

• The Vichy French tanker Alberta

The Vichy French tanker Alberta

• The Italian oiler Strombo

The Italian oiler Strombo

• The German merchant Norburg.

The German merchant Norburg.

• The Italian destroyer Aviere.

The Italian destroyer Aviere.

• The Italian minesweeper Monte Argentario

The Italian minesweeper Monte Argentario

• The Italian merchant (in German service) Trapani.

The Italian merchant (in German service) Trapani.

• An unknown sailing vessel

An unknown sailing vessel

Some extracts from the log of HMS Torbay:

28 May 1941

At 1230 hours (time zone -3) HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) departs Alexandria with orders to patrol in the northern Aegean Sea. (This is HMS Torbay's 2nd Mediterranean War Patrol)

1 Jun 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) sinks a fully laden Greek (German controlled) caique with gunfire in the Doro Channel, Greece.

The vessel was sighted at 0745 hours (time zone -3). At 0936 hours it was noticed that the vessel was wearing the German flag so Torbay surfaced and sank the vessel with five rounds of gunfire 17 nautical miles bearing 87º from Cape Doro.

The 2nd round of gunfire was a hit aft and was followed by a violent explosion which blew the stern off and a cloud of yellow smoke enveloped the target.

At 0943 hours Torbay dived and resumed patrol.

3 Jun 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) sinks a well laden caique with gunfire off Mitylene, Lesbos, Greece.

The vessel was sighted at 1600 hours (time zone -3). At 1643 hours Torbay surfaced and sank the vessel with gunfire 21.5 nautical miles bearing 305 Sigri Island. Torbay submerged at 1651 hours and resumed patrol.

6 Jun 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) torpedoes and damages the Vichy French tanker Alberta (3357 GRT, built 1938) off Cape Hellas.

At 1242 hours (time zone -3) a 3000 ton merchant was sighted. Torbay struggled with the strong current to get into an attack position but at 1415 hours a torpedo was fired, in position 3.5 nautical miles bearing 229º Cape Hellas, that hit the target aft. The ship appeared to be sinking so Torbay left the area to the North-West.

Later Torbay closed in again to finish off the ship. At 1545 hours another torpedo was fired. The target was again hit aft but as the ship was already flooded in that part not much more damage was done. After firing this torpedo Torbay once again left the area to the North-West.

At 1558 hours, Torbay sighted a 1500 ton merchant approaching the Dardanelles from the North, Torbay turned to intercept but the target was later identified as Turkish.

Torbay then turned to the west as battery power was running low. At 2115 hours Torbay surfaced in position 8 nautical miles, bearing 152 Avlaka Point (Imbros) and started to charge her depleted battery's.

See 7 June 1941.

7 Jun 1941

Continuation of the events of 6 June 1941

At 0448 hours (time zone -3) Torbay submerged and closed the entrance to the Dardanelles once again from the west.

At 0600 hours ‘Alberta’ was sighted still afloat and at anchor. The ship was just within Turkish territorial waters and not aground.

At 0751 hours Torbay spotted a merchant of about 1500 tons coming from the entrance of the Dardanelles and gave chase. The ship was later identified as Turkish so it was not attacked.

At 1130 hours Torbay was back at the position where ‘Alberta’ was anchored. The ship appeared deserted. Lt.Cdr. Miers decided not to fire another torpedo but to board the ship after dark to search for valuable documents and to scuttle the ship.

At 1515 hours a small Turkish coaster emerged from the Dardanelles and went alongside ‘Alberta’ but soon continued on to the south.

At 1600 hours a merchant of about 4000 tons was sighted approaching the Dardanelles from the south. The ship was identified as the Turkish Refah (3805 GRT, built 1901) so it was not attacked.

At 2145 hours Torbay surfaced in position 4.7 nautical miles bearing 222º, Cape Hellas.

At 2305 hours Torbay secured alongside ‘Alberta’. It proved however impossible to scuttle the ship as the engine room was completely flooded.

At 2344 hours Torbay slipped and proceeded back out to sea.

At 2359 an explosion was observed aboard Alberta but this failed to sink the ship.

see 8 June 1941.

8 Jun 1941

Continuation of the events of 7 June 1941

At 0050 hours (time zone -3) Torbay stopped in position 10.6 nautical miles bearing 120º Avlaka Point (Imbros) to charge her battery's.

At 0450 hours Torbay submerged in position 7.8 nautical miles bearing 261º, Cape Hellas.

At 0545 hours ‘Alberta’ was observed chattered by fire and aground on the shoal to the North of Rabbit Island. It was decided to leave the ship there in the hope that she would break up in the next gale.

At 1920 hours, Torbay sighted a Turkish merchant ship of about 1500 tons entering the Dardanelles. As bad weather was closing in it was decided to retreat to the northward.

See 9 June 1941

9 Jun 1941

Continuation of the events of 8 June 1941

At 0130 hours (time zone -3), Torbay, in position 6 nautical miles bearing 326º Cape Hellas, sighted a large merchant ships approaching the Dardanelles from the south. Torbay closed to the limit of the territorial waters to identify the target. At 0153 hours the target was identified as Turkish. At 0157 hours Torbay submerged in position 4.8 nautical miles bearing 322º Cape Hellas.

At 0900 hours a 3000 tons merchant was sighted coming out of the Dardanelles. The ship was identified as the Turkish Tirhan (3085 GRT, built 1938). The ship proceeded towards the ‘Alberta’ and attempted to tow her off.

At 1230 hours a 1500 tons merchant was sighted coming out of the straits. Once again the ship was identified as the Turkish, this time the Trak (1500 GRT, built 1938).

At 1700 hours it was observed that the Tirhan had succeeded in towing off the ‘Alberta’ and was heading towards the strait with the ‘Alberta’ in tow. Lt.Cdr. Miers decided that ‘Alberta’ was not allowed to escape and that he had to attack again.

At 1742 hours, in position 2.3 nautical miles bearing 236º Cape Hellas, Torbay fired a torpedo that missed the target. The Turks slipped the tow and the Tirhan fled at high speed into the straits.

At 1815 hours Torbay sighted a merchant ship resembling the German Salzburg. (Torbay was warned that the German Salzburg was about the leave the Dardanelles). The ship turned towards the south and did not leave Turkish territorial waters. No positive identification could be made and Torbay did not manage the get into attack position.

At 1830 hours, as Lt.Cdr. Miers intended to surface to finish off ‘Alberta’ with gunfire when an Italian torpedo boat of the Spica class was sighted only 2.5 nautical miles away. Torbay went deep and retreated to the North towards Lemnos.

At 2237 hours Torbay surfaced in position 12.5 nautical miles bearing 127º Avlaka Point (Imbros).

See 10 June 1941.

10 Jun 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) finally finishes off the Alberta (see 6 June 1941). Torbay also torpedoes the Italian tanker Utilitas (5342 GRT, built 1918). Unfortunately the torpedo failed to explode. Later she torpedoes and sinks Italian tanker Giuseppina Ghirardi (3319 GRT, built 1892).

Continuation of the events of 9 June 1941.

At 0242 hours (time zone -3) Torbay fired 40 rounds and ‘Alberta’ was left ablaze and in a sinking condition 17 nautical miles east of Lemnos.

At 0450 hours, Torbay submerged in position 9.7 nautical miles bearing 270º Cape Hellas.

At 0940 hours, while in position 4.8 nautical miles bearing 259º Cape Hellas a convoy of 6 ships escorted by two Italian torpedo boats was sighted bearing 280, distance 5 nautical miles and course 080 degrees. Lt.Cdr. Miers decided to attack and put Torbay into attack position. This was however frustrated by the movements of the enemy.

At 1043 hours, Lt.Cdr. Miers finally managed to fire three torpedoes against one of the merchant ships in the convoy. After firing the torpedoes Torbay went deep. Two explosions were heard that were linked with a torpedo hitting the target. At 1049 hours five depth charges were dropped. At 1055 hours a full pattern of depth charges exploded fairly close. Between 1100 and 1125 hours more depth charges were dropped but the were not close.

HMS Torbay

At 1140 hours Torbay came to periscope depth. At 1150 hours, while Torbay was in position 6.1 nautical miles bearing 251 Cape Hellas. One of the Italian escorts was sighted patrolling off the entrance to the Dardanelles.

At 1208 hours the Italian tanker Giuseppina Ghirardi (3319 GRT, built 1892) was sighted coming out of the straits. The Italian torpedo boat patrolled a mile ahead. Lt.Cdr. Miers at once turned to attack.

At 1259 hours, in position 8.3 nautical miles bearing 255º Cape Hellas, Torbay fired three torpedoes at a range of 700 yards at the tanker. Two torpedoes hit the target. Torbay went deep and increased to full speed to evade the counter attack. The Italian torpedo boat only dropped two depth charges.

At 1335 hours Torbay came to periscope depth and at 1045 hours, while in position 10.6 nautical miles bearing 250º Cape Helles, sighted the enemy torpedo boat stopped bout two nautical miles to the eastward in the approximate position where the tanker was sunk. Also two MAS boats were seen approaching at high speed from the westward. Torbay went deep again and proceeded on homeward passage in accordance with her orders to leave her patrol area at 2400 hours on the 10th.

At 2200 hours Torbay surfaced in position 21.5 nautical miles bearing 356º Sigri Island (Mytilene) and proceeded south.

11 Jun 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) rams and sinks a Greek caique about 15 nautical miles south off Mitylene, Lesbos, Greece.

At 0030 hours (time zone -3) Torbay, while in position 15.3 nautical miles bearing 328º Sigri Island (Mytilene), sighted a caique making for Mitylene from the west. Lt.Cdr. Miers decided to destroy the vessel by ramming as he did not want to use his gun while he was escaping the area of his previous sinkings.

At 0104 hours Torbay rammed the caique and allowed the Greek crew to abandon ship before completing the destruction.

12 Jun 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) sinks the Italian schooner Gesu E Maria (238 GRT) with gunfire off Skyros, Greece in position 39º10'N, 25º20'E.

At 1115 hours (time zone -3) Torbay sighted a large schooner about three miles away.

At 1218 hours, Lt.Cdr. Miers surfaced and gave chase.

At 1239 hours, Torbay, in position 19 nautical miles bearing 137º Strati Island, opened fire and sank the enemy ship with 25 rounds of gunfire.

At 1252 hours Torbay dived and proceeded to the south.

16 Jun 1941

At 0800 hours (time zone -3) HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) arrives at Alexandria.

28 Jun 1941

At 1600 hours (time zone -3) HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) departs Alexandria with orders to patrol in the Aegean Sea. (This is HMS Torbay's 3rd Mediterranean War Patrol)

30 Jun 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) sinks a sailing vessel with gunfire off Cape Malea, Greece.

At 1810 hours (time zone -3) a laden caique of about 50 tons was spotted. The target was chased.

At 2054 hours Torbay surfaced and sank the caique with gunfire in position 264º Phalconeria Island, 6 nautical miles.

2 Jul 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) torpedoes and sinks the Italian merchant Cittá di Tripoli (2933 GRT, built 1915) in the Zea Channel, Greece in position 37º41'N, 24º15'E.

Cittá di Tripoli

Around 0630 hours (time zone -3), while in position 295º Pt. St.Nikolo (Zea Island) 4.9 nautical miles, two merchants escorted by an Italian torpedo boats of the Libra class was sighted. Overhead of the convoy an aircraft was circling. Torbay took action to get into attack position. (This convoy was made up of the Cittá di Savona (2500 GRT, built 1930) and Cittá di Tripoli (2933 GRT, built 1915) escorted by the Italian torpedo boat Libra and from 0600 (Italian official time) a German aircraft. They were on the way back from Vathi (Samos) where they had landed troops).

At 0722 hours, while in position 304º St. Nokolo 4.5 nautical miles, three torpedoes were fired at the leading merchant from 3300 yards.

At 0724 hours three torpedoes were fired at the rear ship.

At 0725 hours the leading ship was struck by one torpedo.

From 0730 to 0840 hours the escorting Italian torpedo boat dropped 18 single depth charges but none were very close.

(The escorting German aircraft sighted the torpedo tracks and signalled the ships, Cittá di Tripoli attempted coming about but was not quick enough and was hit at 0623 hrs (Italian official time). Cittá di Savona rescued 48 survivors, there were 11 dead).

4 Jul 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) sinks two German sailing vessels with gunfire in the Doro Channel.

At 0615 hours (time zone -3) Torbay sighted a large caique of about 100 tons on a direct course from the Doro Channel from Lemnos. The caique was well filled with troops and stores.

At 0659 hours Torbay surfaced in position 084º Doro Island 8.5 nautical miles and engaged the caique with gunfire. The caique finally sank at 0943 hours.

At 1425 hours, while Torbay was in position 159º Doro Island 6.4 nautical miles, a schooner flying the Nazi colours and approaching the Doro Channel from the north-east was sighted. The schooner was of about 60 tons and well loaded with troops and stores. Torbay surfaced at 1450 hours and engaged the schooner with gunfire from both Lewis guns.

5 Jul 1941

The Italian submarine Jantina (599 tons, built 1933) was torpedoed and sunk in the Aegean south of Mykonos, Greece in position 37º21'N, 25º20'E by the British submarine HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN).

Jantina

At 1946 hours (time zone -3), while Torbay was in position 240º Stapodia Island 11.5 nautical

miles, a submarine was sighted bearing 080º 4 nautical miles away. Torbay at once turned to engage the target.

At 2016 hours 6 torpedoes were fired from 1500 yards. One minute later an explosion was heard followed by a tremendous double explosion 10 seconds later. The explosion shook Torbay violently causing some light damage. When Lt.Cdr. Miers took a look through the periscope an aircraft was seen approaching so he took Torbay deep.

8 Jul 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) sinks the German sailing vessel L XIV with gunfire east off Kythera, Greece.

At 0928 hours (time zone -3) HMS Torbay, while in position 059º Cape Malea 7 nautical miles sights an auxiliary schooner of about 200 tons bearing 317º distance 5 nautical miles course 160º.

At 1122 hours Torbay surfaced in position 164º Cape Malea 7 nautical miles. The schooner was seen to be full of troops and stores and was wearing the German flag. After firing some rounds with the Lewis gun but before fire wirh the 4" gun could be opened an aircraft was spotted so Torbay dived.

The schooner now proceeded westward to flee to Kythera Island. At 1142 hours Torbay surfaced again and resumed the action. The schooner was sunk with 4" gunfire.

9 Jul 1941

Around 0220 hours HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) sinks the German sailing vessels L V and L VI, with gunfire and scuttling charges about 10 nautical miles north of Antikythera, Greece.

At 0220 hours, while Torbay was in position 100º Cape Malea 24 nautical miles a caique was seen on the horizon in very good visibility. Torbay turned to close. While doing so three more caiques were seen about 2 nautical miles apart all stearing the same course. As Torbay had not much ammo left for the deck gun it was decided that thay were to be stopped with one well aimed round of the deck gun, then clear the decks with the Lewis gun and then scuttle them with demolition charges.

At 0320 hours, while in position 126º Cape Malea 22 nautical miles, fire was opened on the first caique with the Lewis gun and the 4" gun. Such a blazing fire was started in the caique that it was not possible to go alongside. Lewis gunfire was continued with until all the occupants were either killed or forced to abandon ship. The caique of about 100 tons was left to burn (This must have been L VI)

At 0327 hours Torbay set course to engage the 2nd caique. At 0357 hours fire was opened on the second caique. Most of the crew took to the water and those who remained on board made signals as if to surrender shouting 'captain is Greek'. The submarine came alongside and the caique was boarded. A German soldier tried to throw a grenade but he was shot before he could do so. The whole crew turned out to be Germans and they were forced to launch their rubber boat and jump into it. Another German was shot by Torbay's navigating officer when he tried to shoot this officer with a rifle from point blank range. The caique was of about 100 tons, was carrying troop, ammo and petrol. She had L V painted on her side. This caique was fitted with demolition charges. The German soldiers in the rubber boat were shot by the Lewis gun to prevent them from returning to their ship. At 0435 hours the demolition charges exploded and the caique was sunk.

Around 0530 hours HMS Torbay sinks the German sailing vessel L XII with gunfire and scuttling charges about 10 nautical miles north of Anti-Kythera, Greece.

At 0445 hours a third sailing vessel was sighted, a large auxiliary schooner of about 300 tons making for Anti-Kythera. Torbay chased at full speed but as the target was making a good 10 knots it was not until 0530 that Torbay was close to the target. By that time it was daylight and boarding was out of the question.

At 0530 hours, while Torbay was in position 068º Pori Island 11.5 nautical miles, fire was opened. The schooner was filled with petrol and explosives and was quickly ablaze from stem to stern. Torbay dived soon after. This schooner was seen to sink at 0900 hours. The fourth caique escaped due to the arrival of an aircraft.

10 Jul 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) torpedoes and damages the Italian oiler Strombo (5232 GRT, built 1923) in the Zea Channel in position 37º30'N, 24º16'E.

At 1355 hours, while Torbay was in position 325º Cape Tamelos (Zea Island) 6.4 nautical miles, an Arado 95 aircraft was sighted. This aircraft appeared to be an escort for the Italian tanker Strombo that was expected to arrive in this position shortly. At 1430 hours smoke was sighted in the direction of the aircraft.

At 1446 hours the Strombo was sighted and an attack was commenced. The Strombo was escorted by the above aircraft and an Italian torpedo boat of the Curtatone class that was zig-zagging about half a mile ahead of the target (according to Italian official history this was the Monzambano, indeed a torpedo boats of the Curtatone class).

At 1552 hours, while Torbay was in position 269º Pt. St.Nikolo 6.6 nautical miles, four torpedoes were fired from 1200 yards. Two hits were obtained.

From 1555 to 1620 hours Torbay was counter attacked by the escort with 13 single depth charges some of which were extremely close. At 1630 hours Torbay came to periscope depth and saw that the tanker had sunk and that the aircraft and escorting torpedo boat were searching to the northward. Torbay went deep again. (According to Italian official history the tanker did not sink, she was taken in tow to Salamis by the Monzambano, there were two dead among the crew).

At 1700 hours a fairly loud explosion was heard, which might have been a bomb, Torbay went still deeper.

At 1750 hours Torbay returned to periscope depth and saw two 'destroyers' coming towards her. (these were

the Italian torpedo boats Climene and Calatafimi). From 1800 to 1920 hours Torbay was hunted. 25 Depth

charges were dropped but none were very close.

As Torbay was now out of torpedoes and had only 19 rounds for her deck gun left, Lt.Cdr. Miers decided

to proceed to Alexandria.

15 Jul 1941

At 0800 hours (time zone -3) HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) arrives at Alexandria.

12 Aug 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) attacks an Italian convoy 4 nautical miles west of Benghazi, Libya. The four torpedoes fired against the Italian merchants Bosforo (3648 GRT) and Iseo (2366 GRT) all miss their targets and Torbay is heavily depth charged following this attack by the Italian torpedo boat Partenope.

16 Aug 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) sinks the sailing vessel Evangelista (28 GRT) with scuttling charges in position 106º Cape Matapan 1.3 nautical miles.

10 Sep 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, RN) torpedoes and damages the German merchant Norburg (2392 GRT) inside Iraklion harbour, Crete. The damaged German merchant settles on the bottom of the harbour but is later salvaged.

11 Dec 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, DSO, RN) sinks the Greek sailing vessel Sofia (800 GRT) with gunfire north-west of Suda Bay, Crete.

12 Dec 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, DSO, RN) sinks the Greek sailing vessel P III with gunfire north-west of Suda Bay,

Crete.

15 Dec 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, DSO, RN) sinks three Greek sailing vessels with gunfire off Cape Methene.

22 Dec 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, DSO, RN) sinks a Greek sailing vessel with gunfire off Cape Methene.

23 Dec 1941

HMS Torbay (Lt.Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, DSO, RN) torpedoes and further damages the Italian destroyer Aviere (1645 tons) at Navarino harbour. The ‘Aviere’ was already grounded after being damaged on 19 November 1941 by the Polish submarine ORP Sokol.

27 Feb 1942

HMS Torbay (Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, DSO, RN) torpedoes and sinks the Italian merchant Lido (1243 GRT) about 15 nautical miles south of Antipaxe, Korfu, Greece.

5 Mar 1942

HMS Torbay (Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, DSO, RN) torpedoes and sinks the Italian merchant Maddalena G. (5212 GRT) off Korfu, Greece.

9 Apr 1942

HMS Torbay (Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, DSO and Bar, RN) sinks the Italian auxiliary patrol vessel R 113 / Avanguardista (34 GRT) with gunfire off Patras, Greece.

11 Apr 1942

HMS Torbay (Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, DSO and Bar, RN) sinks the Italian sailing vessel Gesu Crocifisso (137 GRT) with gunfire north-west of Korfu.

18 Apr 1942

HMS Torbay (Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, DSO and Bar, RN) torpedoes and sinks the German army cargo ship Bellona (1297 GRT) in the Ionian Sea about 50 nautical miles east-south-east of Capo Colonna, Italy in position 38º52'N, 18º15'E.

19 Apr 1942

HMS Torbay (Cdr. A.C.C. Miers, DSO and Bar, RN) sinks the German auxiliary submarine chaser 13 V 2 / Delpa II (170 GRT) with gunfire north of Crete in position 36º36'N, 24º15'E.

Partenope

Aviere

Use of ‘Jolly Roger’ by British Submarine Service

The flags themselves were always unofficial, which accounts for the different symbols for the same kind of operation, or the symbols which were used only by one boat, like the tin opener (or the stork and baby flag flown on one occasion by HM S/M United after a mission of mercy).

Some further symbols:

• crossed sabres - boardings

crossed sabres - boardings

• dog - operation "Husky" (invasion on Sicily 1943)

• grating - forced net barrier

grating - forced net barrier

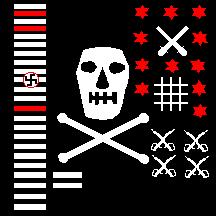

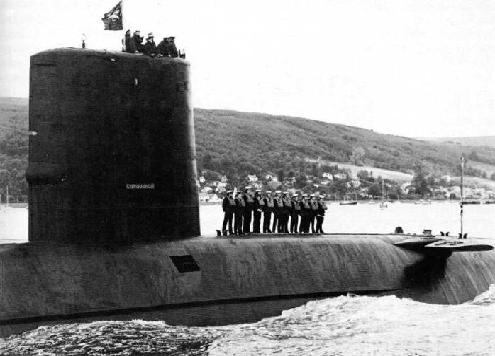

‘HMS Conqueror’ flying ‘Jolly Roger’ after sinking Argentine heavy cruiser ‘General Belgrano’ during the 1982 Falklands War

‘General Belgrano’

‘HMS Conqueror’

‘HMS Conqueror’