Tiger Roche

Swashbuckling Irish Soldier of Fortune

‘Tiger’ Roche was a celebrated soldier, duellist and adventurer, variously hailed as a hero and damned as a thief and a murderer at many times during his stormy life. He appeared as the hero in a play by John Masefield and may have been the model for William Makepeace Thackeray’s novel ‘Barry Lyndon’.

‘Tiger’ Roche was a celebrated soldier, duellist and adventurer, variously hailed as a hero and damned as a thief and a murderer at many times during his stormy life. He appeared as the hero in a play by John Masefield and may have been the model for William Makepeace Thackeray’s novel ‘Barry Lyndon’.

Among the characters distinguished for unbridled indulgence and fierce passion, who were all too frequently to be met with in Ireland in the 1700s, was one whose name attained so much celebrity as to become a proverb. ‘Tiger Roche,’ as he was called, was a native of Dublin, where he was born in the year 1729, either the first or second of three sons, to Jordan Roche and Ellen White. His younger brother was Sir Boyle Roche, the eminent politician.

Among the characters distinguished for unbridled indulgence and fierce passion, who were all too frequently to be met with in Ireland in the 1700s, was one whose name attained so much celebrity as to become a proverb. ‘Tiger Roche,’ as he was called, was a native of Dublin, where he was born in the year 1729, either the first or second of three sons, to Jordan Roche and Ellen White. His younger brother was Sir Boyle Roche, the eminent politician.

He received the best education the metropolis could afford, and was instructed in all the accomplishments then deemed essential to the rank and character of a gentleman. So expert was he in the various acquirements of polite life, that at the age of 16 he recommended himself to Lord Chesterfield, then Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, who offered him, gratuitously, a commission in the army; but his friends, having other views for him, declined it. This seems to have been a serious misfortune to the young man, whose disposition and education strongly inclined him to a military life. His hopes were raised, his vanity flattered, by the notice and offer of the viceroy; and in sullen resentment he absolutely refused to embark in any other profession his friends designed for him. He continued, therefore, for several years among the dissipated idlers of the metropolis, having no laudable pursuit to occupy his time, and led into all the outrages and excesses which then disgraced Dublin.

He received the best education the metropolis could afford, and was instructed in all the accomplishments then deemed essential to the rank and character of a gentleman. So expert was he in the various acquirements of polite life, that at the age of 16 he recommended himself to Lord Chesterfield, then Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, who offered him, gratuitously, a commission in the army; but his friends, having other views for him, declined it. This seems to have been a serious misfortune to the young man, whose disposition and education strongly inclined him to a military life. His hopes were raised, his vanity flattered, by the notice and offer of the viceroy; and in sullen resentment he absolutely refused to embark in any other profession his friends designed for him. He continued, therefore, for several years among the dissipated idlers of the metropolis, having no laudable pursuit to occupy his time, and led into all the outrages and excesses which then disgraced Dublin.

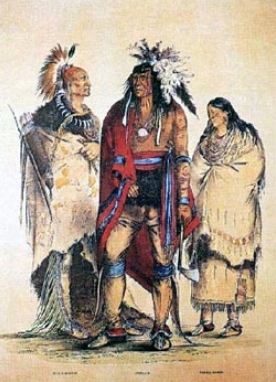

One night, in patrolling the city with his drunken associates, they attacked and killed a watchman, who, with others, had attempted to quell a riot they had excited. He was, therefore, compelled to fly from Dublin. He made his way to Cork, where he lay concealed for some time, and from thence escaped to the plantations in North America. When the war broke out between France and England, he entered as a volunteer in one of the provincial regiments, and distinguished himself against the French and Indian allies, during which he seems to have acquired those fierce and cruel qualities by which those Indian tribes were distinguished.

One night, in patrolling the city with his drunken associates, they attacked and killed a watchman, who, with others, had attempted to quell a riot they had excited. He was, therefore, compelled to fly from Dublin. He made his way to Cork, where he lay concealed for some time, and from thence escaped to the plantations in North America. When the war broke out between France and England, he entered as a volunteer in one of the provincial regiments, and distinguished himself against the French and Indian allies, during which he seems to have acquired those fierce and cruel qualities by which those Indian tribes were distinguished.

The Noble Society of Celts, is an hereditary society of persons with Celtic roots and

interests, who are of noble title and gentle birth, and who

have come together in a search for, and celebration of, things Celtic.

"Fall / Autumn Edition 2010"

He was then particularly noticed by his officers for the intrepidity and spirit he displayed, and was high in favour with Colonel Massy, his commanding officer; but an accident occurred of so humiliating and degrading a nature, as to extinguish at once all his hopes of advancement. An officer of Massy's regiment was possessed of a very valuable fowling-piece (shot gun) which he highly prized. He missed it from his tent and made diligent inquiry after it, but it was nowhere to be found. It was, however, reported that it was seen in the possession of Roche, and an order was made to examine his baggage. On searching among it the lost article was found. Roche declared that he had bought it from one Bourke, a countryman of his own, and a corporal in his regiment. Bourke was sent for and examined. He solemnly declared on oath that the statement of Roche was altogether false, and that he himself knew nothing at all of the transaction. Roche was now brought to a court-martial, and little appearing in his favour, he was convicted of the theft, and, as a lenient punishment, ordered to quit the service with every mark of disgrace and ignominy.

He was then particularly noticed by his officers for the intrepidity and spirit he displayed, and was high in favour with Colonel Massy, his commanding officer; but an accident occurred of so humiliating and degrading a nature, as to extinguish at once all his hopes of advancement. An officer of Massy's regiment was possessed of a very valuable fowling-piece (shot gun) which he highly prized. He missed it from his tent and made diligent inquiry after it, but it was nowhere to be found. It was, however, reported that it was seen in the possession of Roche, and an order was made to examine his baggage. On searching among it the lost article was found. Roche declared that he had bought it from one Bourke, a countryman of his own, and a corporal in his regiment. Bourke was sent for and examined. He solemnly declared on oath that the statement of Roche was altogether false, and that he himself knew nothing at all of the transaction. Roche was now brought to a court-martial, and little appearing in his favour, he was convicted of the theft, and, as a lenient punishment, ordered to quit the service with every mark of disgrace and ignominy.

Irritated with this treatment, Roche immediately challenged the officer who had prosecuted him to a duel. That officer refused to meet him on the field of honour, on the pretext that ‘Tiger’ was a degraded man, and no longer entitled to the rank and consideration of a gentleman. Stung to madness, and no longer master of himself; ‘Tiger’ rushed to the parade, insulted the officer in the grossest terms, and then flew to the picket-guard, where he attacked the corporal with his naked sword, declaring his intention to kill him on the spot. The man with difficulty defended his life, until his companions sprang upon Roche and disarmed him.

Irritated with this treatment, Roche immediately challenged the officer who had prosecuted him to a duel. That officer refused to meet him on the field of honour, on the pretext that ‘Tiger’ was a degraded man, and no longer entitled to the rank and consideration of a gentleman. Stung to madness, and no longer master of himself; ‘Tiger’ rushed to the parade, insulted the officer in the grossest terms, and then flew to the picket-guard, where he attacked the corporal with his naked sword, declaring his intention to kill him on the spot. The man with difficulty defended his life, until his companions sprang upon Roche and disarmed him.

Though deprived of his weapon, he did not desist from his intention; crouching down like an Indian foe, he suddenly sprung at his antagonist, and fastened on his throat with his teeth; and before he could he disengaged nearly strangled him, dragging away a mouthful of flesh, which, in true Indian spirit, be afterwards said, was “the sweetest morsel he had ever tasted.” From the fierce and savage character he displayed on this occasion, he obtained the appellation of ‘Tiger,’ an affix which was ever after joined to his name.

Though deprived of his weapon, he did not desist from his intention; crouching down like an Indian foe, he suddenly sprung at his antagonist, and fastened on his throat with his teeth; and before he could he disengaged nearly strangled him, dragging away a mouthful of flesh, which, in true Indian spirit, be afterwards said, was “the sweetest morsel he had ever tasted.” From the fierce and savage character he displayed on this occasion, he obtained the appellation of ‘Tiger,’ an affix which was ever after joined to his name.

A few days after, the English army advanced to force the lines of Ticonderaga. Unfortunately Roche was left desolate and alone in the wilderness, an outcast from society, apparently abandoned by all the world. His resolution and fidelity to his cause, however, did not desert him. He pursued his way through the woods till he fell in with a party of friendly Indians, and by extraordinary exertions and forced marches, arrived at the fortress with them, to join in the attack. He gave distinguished proofs of his courage and military abilities during that unfortunate affair, and received four dangerous wounds. He attracted the notice of General Abercrombie, the leader of the expedition; but the stain of robbery was upon him, and no services, however brilliant, could obliterate it.

A few days after, the English army advanced to force the lines of Ticonderaga. Unfortunately Roche was left desolate and alone in the wilderness, an outcast from society, apparently abandoned by all the world. His resolution and fidelity to his cause, however, did not desert him. He pursued his way through the woods till he fell in with a party of friendly Indians, and by extraordinary exertions and forced marches, arrived at the fortress with them, to join in the attack. He gave distinguished proofs of his courage and military abilities during that unfortunate affair, and received four dangerous wounds. He attracted the notice of General Abercrombie, the leader of the expedition; but the stain of robbery was upon him, and no services, however brilliant, could obliterate it.

From hence he made his way to New York, after suffering incredible afflictions from pain, poverty, and sickness. One man alone, Governor Rogers, pitied his case, and was not satisfied of his guilt. In the year 1758, Roche received from his friends in Ireland a reluctant supply of money, which enabled him to obtain a passage on board a vessel bound for England, where he arrived shortly afterwards. He reserved part of his supply of money for the purchase of a commission, and hoped once more to ascend to that rank from which he had been, as he thought, unjustly degraded; but just as the purchase was about to be completed, a report of his theft in America reached the regiment, and the officers refused to serve with him.

From hence he made his way to New York, after suffering incredible afflictions from pain, poverty, and sickness. One man alone, Governor Rogers, pitied his case, and was not satisfied of his guilt. In the year 1758, Roche received from his friends in Ireland a reluctant supply of money, which enabled him to obtain a passage on board a vessel bound for England, where he arrived shortly afterwards. He reserved part of his supply of money for the purchase of a commission, and hoped once more to ascend to that rank from which he had been, as he thought, unjustly degraded; but just as the purchase was about to be completed, a report of his theft in America reached the regiment, and the officers refused to serve with him.

With great perseverance and determined resolution, he traced the origin of the report to a Captain Campbell, then residing at the British Coffee-house, in Charing-cross. He met him in the public room, taxed him with what he called a gross and false calumny, which the other retorted with great spirit. A duel immediately ensued, in which both were desperately wounded.

With great perseverance and determined resolution, he traced the origin of the report to a Captain Campbell, then residing at the British Coffee-house, in Charing-cross. He met him in the public room, taxed him with what he called a gross and false calumny, which the other retorted with great spirit. A duel immediately ensued, in which both were desperately wounded.

Roche now declared in all public places, and caused it to be everywhere known, that, as he could not obtain justice on the miscreant who had traduced his character in America, he would personally chastise every man in England who presumed to propagate the report. With this determination, he met one day, in the Green Park, his former colonel, Massy, and another officer, who had just returned home. He addressed them, and anxiously requested they would, as they might, remove the stain from his character. They treated his appeal with contempt, when he fiercely attacked them both. They immediately drew their swords, and disarmed him. A crowd of spectators assembled round and being two to one they inflicted a severe beating on Roche.

Roche now declared in all public places, and caused it to be everywhere known, that, as he could not obtain justice on the miscreant who had traduced his character in America, he would personally chastise every man in England who presumed to propagate the report. With this determination, he met one day, in the Green Park, his former colonel, Massy, and another officer, who had just returned home. He addressed them, and anxiously requested they would, as they might, remove the stain from his character. They treated his appeal with contempt, when he fiercely attacked them both. They immediately drew their swords, and disarmed him. A crowd of spectators assembled round and being two to one they inflicted a severe beating on Roche.

Foiled in his attempt, ‘Tiger’ immediately determined to seek another opportunity to confront them, and finding that one of them had departed for Chester, Roche set out after him with the indefatigable perseverance and pursuit of a bloodhound. Here Roche again sought him, and meeting him in the streets, again attacked him. Roche was, however, again defeated, and received a severe wound in the sword-arm, which long disabled him. But the redress that he desperately sought for the repair of his character and good name now came accidentally and unexpectedly – and was something which all his activity and perseverance could not obtain. Bourke, the corporal who had denied selling him the stolen shot-gun, was mortally wounded by a scalping party of American 'Red' Indians. And on his death-bed Bourke made a solemn confession that he himself had actually stolen the fowling-piece, and then sold it to Roche, without informing him by what means he had procured it, and that Roche had really purchased it without any suspicion of the theft. This declaration of the dying man was properly attested, and universally received, and restored the injured Roche at once to good character and countenance.

Foiled in his attempt, ‘Tiger’ immediately determined to seek another opportunity to confront them, and finding that one of them had departed for Chester, Roche set out after him with the indefatigable perseverance and pursuit of a bloodhound. Here Roche again sought him, and meeting him in the streets, again attacked him. Roche was, however, again defeated, and received a severe wound in the sword-arm, which long disabled him. But the redress that he desperately sought for the repair of his character and good name now came accidentally and unexpectedly – and was something which all his activity and perseverance could not obtain. Bourke, the corporal who had denied selling him the stolen shot-gun, was mortally wounded by a scalping party of American 'Red' Indians. And on his death-bed Bourke made a solemn confession that he himself had actually stolen the fowling-piece, and then sold it to Roche, without informing him by what means he had procured it, and that Roche had really purchased it without any suspicion of the theft. This declaration of the dying man was properly attested, and universally received, and restored the injured Roche at once to good character and countenance.

His former slanderers now vied with each other in friendly offers to assist him; and as a remuneration for the injustice and injury he had suffered, a lieutenancy in a newly-raised regiment was conferred upon him gratuitously. He soon returned to Dublin (where the old murder charge had been quietly dropped) as a much-celebrated hero; the reputation of the injuries he had sustained, the gallant part he had acted, and the romantic adventures he had encountered among the Indians, in the forests of America, were the subject of every conversation. Convivial parties were everywhere arranged in his honour. Wherever he appeared, he was the lion of the night. A handsome person, made still more attractive by the wounds he had received, a graceful form in the dance, in which he excelled, and the narrative of “his hairbreadth ‘scapes,” with which he was never too diffident to indulge the company, made him at this time “the observed of all observers” in the metropolis of Ireland.

His former slanderers now vied with each other in friendly offers to assist him; and as a remuneration for the injustice and injury he had suffered, a lieutenancy in a newly-raised regiment was conferred upon him gratuitously. He soon returned to Dublin (where the old murder charge had been quietly dropped) as a much-celebrated hero; the reputation of the injuries he had sustained, the gallant part he had acted, and the romantic adventures he had encountered among the Indians, in the forests of America, were the subject of every conversation. Convivial parties were everywhere arranged in his honour. Wherever he appeared, he was the lion of the night. A handsome person, made still more attractive by the wounds he had received, a graceful form in the dance, in which he excelled, and the narrative of “his hairbreadth ‘scapes,” with which he was never too diffident to indulge the company, made him at this time “the observed of all observers” in the metropolis of Ireland.

But a service which he rendered the public in Dublin deservedly placed him very high in their esteem and goodwill. It was at this time infested with those miscreants mentioned earlier, ‘sweaters,’ or ‘pinkindindies’ (who cut off the points of their swords because they would rather "inflict considerable pain" than kill), and every night some outrage was perpetrated on the peaceable and unoffending inhabitants. One evening late, an old gentleman with his son and daughter were returning home from a friend's house, when they were attacked on Ormond Quay by a party of them. Roche, who was accidentally going the same way at the same time, heard the shrieks of a woman crying for assistance, and instantly rushed to the place. Here he did not hesitate singly to meet the whole party. He first rescued the young woman from the ruffian who held her, and then attacking the band, he desperately wounded some, and put the rest to flight.

But a service which he rendered the public in Dublin deservedly placed him very high in their esteem and goodwill. It was at this time infested with those miscreants mentioned earlier, ‘sweaters,’ or ‘pinkindindies’ (who cut off the points of their swords because they would rather "inflict considerable pain" than kill), and every night some outrage was perpetrated on the peaceable and unoffending inhabitants. One evening late, an old gentleman with his son and daughter were returning home from a friend's house, when they were attacked on Ormond Quay by a party of them. Roche, who was accidentally going the same way at the same time, heard the shrieks of a woman crying for assistance, and instantly rushed to the place. Here he did not hesitate singly to meet the whole party. He first rescued the young woman from the ruffian who held her, and then attacking the band, he desperately wounded some, and put the rest to flight.

His spirited conduct on this occasion gained him a high and deserved reputation, and inspired others with resolution to follow his example. He formed a body, consisting of officers and others of his acquaintance, to patrol the dangerous streets of Dublin at night, and so gave that protection to the citizens which the miserable and decrepit watch were not able to afford.

His spirited conduct on this occasion gained him a high and deserved reputation, and inspired others with resolution to follow his example. He formed a body, consisting of officers and others of his acquaintance, to patrol the dangerous streets of Dublin at night, and so gave that protection to the citizens which the miserable and decrepit watch were not able to afford.

But he was not fated long to preserve the high character he had acquired. His physical temperament, impossible to manage, and his moral perceptions, hard to regulate, were the sport of every contingency and vicissitude of fortune. The peace concluded in 1763 reduced the army, and he retired in indigent circumstances to London, where he soon lived beyond his income. In order to repair it, he courted a Miss Pitt, who had a fortune of £4,000 (approximately £100,000 in today's money).On the anticipation of this, he engaged in a career of extravagance that soon accumulated debts to a greater amount, and the marriage portion was insufficient to satisfy his creditors. He was arrested and cast into the prison of the King’s Bench, where various detainers were laid upon him, and be was doomed to a confinement of hopeless termination. Here his mind appears to have been completely broken down, and the intrepid and daring courage, which had sustained him in so remarkable a manner through all the vicissitudes of his former life, seemed to be totally exhausted. He submitted to insults and indignities with patience, and seemed deprived not only of the capability to resent, but of the sensibility to feel them.

But he was not fated long to preserve the high character he had acquired. His physical temperament, impossible to manage, and his moral perceptions, hard to regulate, were the sport of every contingency and vicissitude of fortune. The peace concluded in 1763 reduced the army, and he retired in indigent circumstances to London, where he soon lived beyond his income. In order to repair it, he courted a Miss Pitt, who had a fortune of £4,000 (approximately £100,000 in today's money).On the anticipation of this, he engaged in a career of extravagance that soon accumulated debts to a greater amount, and the marriage portion was insufficient to satisfy his creditors. He was arrested and cast into the prison of the King’s Bench, where various detainers were laid upon him, and be was doomed to a confinement of hopeless termination. Here his mind appears to have been completely broken down, and the intrepid and daring courage, which had sustained him in so remarkable a manner through all the vicissitudes of his former life, seemed to be totally exhausted. He submitted to insults and indignities with patience, and seemed deprived not only of the capability to resent, but of the sensibility to feel them.

On one occasion he had a trifling dispute with a fellow-prisoner, who kicked him, and struck him a blow in the face. There was a time when his fiery spirit would not have been satisfied but with the blood of the offender. He now only turned aside and cried like a child. It happened that his countryman, Buck English, whom we have before noticed, was confined at the same time in the Bench; with him also he had some dispute, and English, seizing a stick, flogged him in a savage manner. Roche made no attempt to retaliate or resist, but crouched under the punishment.

On one occasion he had a trifling dispute with a fellow-prisoner, who kicked him, and struck him a blow in the face. There was a time when his fiery spirit would not have been satisfied but with the blood of the offender. He now only turned aside and cried like a child. It happened that his countryman, Buck English, whom we have before noticed, was confined at the same time in the Bench; with him also he had some dispute, and English, seizing a stick, flogged him in a savage manner. Roche made no attempt to retaliate or resist, but crouched under the punishment.

But while he shrunk thus under the chastisement of men, he turned upon his wife, whom he treated with such cruelty, that she was compelled to separate from him, and abandon him to his fate. At length, however, an act of grace liberated him from a confinement under which all his powers were fast sinking; and a small legacy, left him by a relation, enabled him once more to appear in the world of high society.

But while he shrunk thus under the chastisement of men, he turned upon his wife, whom he treated with such cruelty, that she was compelled to separate from him, and abandon him to his fate. At length, however, an act of grace liberated him from a confinement under which all his powers were fast sinking; and a small legacy, left him by a relation, enabled him once more to appear in the world of high society.

With his change of fortune a change of disposition came over him; and in proportion as he had shown an abject spirit in confinement, he now exhibited even a still more arrogant and irritable temper than he had ever before displayed. He was a constant frequenter of billiard-tables, where he indulged an insufferable assumption, with sometimes a shrewd and keen remark.

With his change of fortune a change of disposition came over him; and in proportion as he had shown an abject spirit in confinement, he now exhibited even a still more arrogant and irritable temper than he had ever before displayed. He was a constant frequenter of billiard-tables, where he indulged an insufferable assumption, with sometimes a shrewd and keen remark.

One day he was idly pushing balls around a table, and someone complained that while he was not playing himself, he was "hindering other gentlemen from their amusement." "Gentlemen!" said Roche, "why, sir, except you and me, and two or three more, there is not a gentleman in the room." His friend afterwards remarked that he had grossly offended a large company, and wondered some of them had not and resented the affront. "Oh! " said Roche, "there was no fear of that. There was not a thief in the room that did not consider himself one of the two or three gentlemen I excepted."

One day he was idly pushing balls around a table, and someone complained that while he was not playing himself, he was "hindering other gentlemen from their amusement." "Gentlemen!" said Roche, "why, sir, except you and me, and two or three more, there is not a gentleman in the room." His friend afterwards remarked that he had grossly offended a large company, and wondered some of them had not and resented the affront. "Oh! " said Roche, "there was no fear of that. There was not a thief in the room that did not consider himself one of the two or three gentlemen I excepted."

Again his fortune seemed in the ascendant, and the miserable, spiritless, flogged and degraded prisoner of the King's Bench was called on to stand as candidate to represent Middlesex in Parliament. So high an opinion was entertained of his daring spirit, that it was thought by some of the popular party he might be of use in intimidating Colonel Luttrell, who was the declared opponent of John Wilkes at that election. In April, 1769, he was put into nomination at Brentford by Mr. Jones, and seconded by Mr. Martin, two highly popular electors.

Again his fortune seemed in the ascendant, and the miserable, spiritless, flogged and degraded prisoner of the King's Bench was called on to stand as candidate to represent Middlesex in Parliament. So high an opinion was entertained of his daring spirit, that it was thought by some of the popular party he might be of use in intimidating Colonel Luttrell, who was the declared opponent of John Wilkes at that election. In April, 1769, he was put into nomination at Brentford by Mr. Jones, and seconded by Mr. Martin, two highly popular electors.

He, however, disappointed his friends, and declined the poll, induced, it was said, by promises of Luttrell's friends to provide for him. On this occasion he fought another duel with a Captain Flood, who had offended him in a coffee-house. He showed no deficiency of courage, but on the contrary even a larger proportion of spirit and generosity than had distinguished him at former periods. Returning at this time one night to his apartments at Chelsea, he was attacked by two ruffians, who presented pistols to his breast. He sprang back, and drew his sword, when one of them fired at him, and the ball grazed his temple. He then attacked them both, pinned one to the wall, and the other fled.

He, however, disappointed his friends, and declined the poll, induced, it was said, by promises of Luttrell's friends to provide for him. On this occasion he fought another duel with a Captain Flood, who had offended him in a coffee-house. He showed no deficiency of courage, but on the contrary even a larger proportion of spirit and generosity than had distinguished him at former periods. Returning at this time one night to his apartments at Chelsea, he was attacked by two ruffians, who presented pistols to his breast. He sprang back, and drew his sword, when one of them fired at him, and the ball grazed his temple. He then attacked them both, pinned one to the wall, and the other fled.

Roche secured his prisoner, and the other was apprehended next day. They were tried at the “Old Bailey” (a famous magistrates’ court in London), and capitally convicted; but at the humane and earnest intercession of Roche their punishment was mitigated to transportation to penal colonies in the “new World

Roche secured his prisoner, and the other was apprehended next day. They were tried at the “Old Bailey” (a famous magistrates’ court in London), and capitally convicted; but at the humane and earnest intercession of Roche their punishment was mitigated to transportation to penal colonies in the “new World

All the fluctuations of this strange man's character seemed at length to settle into one unhappy state, from which he was unable ever again to raise himself. He met with a young person, walking with her mother in St James's Park, and was struck with her appearance. He insinuated himself into their acquaintance, and the young lady formed for him a strong and uncontrollable attachment. She possessed a considerable fortune, of which Roche became the manager. His daily profusion and dissipation soon exhausted her property, and the mother and daughter were compelled to leave London, reduced to indigence and distress, in consequence of the debts in which he had involved them.

All the fluctuations of this strange man's character seemed at length to settle into one unhappy state, from which he was unable ever again to raise himself. He met with a young person, walking with her mother in St James's Park, and was struck with her appearance. He insinuated himself into their acquaintance, and the young lady formed for him a strong and uncontrollable attachment. She possessed a considerable fortune, of which Roche became the manager. His daily profusion and dissipation soon exhausted her property, and the mother and daughter were compelled to leave London, reduced to indigence and distress, in consequence of the debts in which he had involved them.

He was soon after appointed captain of a company of foot in the East India Service, and embarked in the Sailing Ship "Vansittart," for India, in May, 1778. He had not been many days on board, when such was his impracticable temper that he fell out with all the passengers, and among the rest with a Captain Ferguson, who called him out to duel as soon as they arrived at Madeira. Roche was again seized with a sudden and unaccountable fit of terror, and made submission. The arrogance and cowardice he displayed revolted the whole body of the passengers, and they unanimously made it a point that the captain should expel him from the table. He was driven, therefore, to the society of the common sailors and soldiers on board the ship. With them he endeavoured to ingratiate himself; by mixing freely with them, and denouncing vengeance against every gentleman and officer on board the ship; but his threats were particularly directed against Ferguson, whom he considered the origin of the disgrace he suffered.

He was soon after appointed captain of a company of foot in the East India Service, and embarked in the Sailing Ship "Vansittart," for India, in May, 1778. He had not been many days on board, when such was his impracticable temper that he fell out with all the passengers, and among the rest with a Captain Ferguson, who called him out to duel as soon as they arrived at Madeira. Roche was again seized with a sudden and unaccountable fit of terror, and made submission. The arrogance and cowardice he displayed revolted the whole body of the passengers, and they unanimously made it a point that the captain should expel him from the table. He was driven, therefore, to the society of the common sailors and soldiers on board the ship. With them he endeavoured to ingratiate himself; by mixing freely with them, and denouncing vengeance against every gentleman and officer on board the ship; but his threats were particularly directed against Ferguson, whom he considered the origin of the disgrace he suffered.

On the arrival of the ship at Cape Town on the southern tip of Africa, and after all the passengers were disembarked, Roche came ashore, in the dusk of the evening, and was seen about the door of the house where Ferguson lodged. A message was conveyed to Ferguson, who went out, and was found soon afterwards round the corner of the house, weltering in his blood, with nine deep wounds, all on his left side; and it was supposed they must have been there inflicted, because it was the unprotected side, and the attack was made when he was off his guard.

On the arrival of the ship at Cape Town on the southern tip of Africa, and after all the passengers were disembarked, Roche came ashore, in the dusk of the evening, and was seen about the door of the house where Ferguson lodged. A message was conveyed to Ferguson, who went out, and was found soon afterwards round the corner of the house, weltering in his blood, with nine deep wounds, all on his left side; and it was supposed they must have been there inflicted, because it was the unprotected side, and the attack was made when he was off his guard.

Suspicion immediately fixed on Roche as the murderer; he fled during the night, and took refuge among the native African ‘kaffirs’. It was supposed that he ended his strange and eventful life soon after. The Cape was at that time a colony of the Dutch, who, vigilant and suspicious of strangers, suffered none to enter there, but merely to touch for provisions, and pass on. The proceedings, therefore, of their colonial government were shut up in mystery. It was reported at the time, that Roche was demanded and given up to the Dutch authorities of the Cape of Good Hope colony, who caused him to be broken alive upon the wheel, according to the then Dutch criminal law of the Cape, which inflicted that punishment on the more atrocious murderers, and the uncertainty that hung about the circumstance assorted strangely with the wild character of the man.

Suspicion immediately fixed on Roche as the murderer; he fled during the night, and took refuge among the native African ‘kaffirs’. It was supposed that he ended his strange and eventful life soon after. The Cape was at that time a colony of the Dutch, who, vigilant and suspicious of strangers, suffered none to enter there, but merely to touch for provisions, and pass on. The proceedings, therefore, of their colonial government were shut up in mystery. It was reported at the time, that Roche was demanded and given up to the Dutch authorities of the Cape of Good Hope colony, who caused him to be broken alive upon the wheel, according to the then Dutch criminal law of the Cape, which inflicted that punishment on the more atrocious murderers, and the uncertainty that hung about the circumstance assorted strangely with the wild character of the man.

It appears, however, he was tried by the Dutch authorities at the Cape, and acquitted. He then took a passage in a French vessel to Bombay; but the "Vansittart," in which he had come from England to the Cape, had arrived in India before him; information had been given to the British authorities, charging Roche with Ferguson's murder; and Roche was arrested as soon as he landed. He urged his right to be discharged, or at least bailed, on the grounds that there was not sufficient evidence against him; that he had been already acquitted; and that as the offence, if any, was committed out of the British dominions, he could only be tried by special commission, and it was uncertain whether the Crown would issue one or not; or, if the Crown did grant a commission, when or where it would sit. He argued his own case with the skill of a practised lawyer. The authorities, however, declined either to bail or discharge him, and he was kept in custody until he was sent a prisoner to England, to stand his trial.

It appears, however, he was tried by the Dutch authorities at the Cape, and acquitted. He then took a passage in a French vessel to Bombay; but the "Vansittart," in which he had come from England to the Cape, had arrived in India before him; information had been given to the British authorities, charging Roche with Ferguson's murder; and Roche was arrested as soon as he landed. He urged his right to be discharged, or at least bailed, on the grounds that there was not sufficient evidence against him; that he had been already acquitted; and that as the offence, if any, was committed out of the British dominions, he could only be tried by special commission, and it was uncertain whether the Crown would issue one or not; or, if the Crown did grant a commission, when or where it would sit. He argued his own case with the skill of a practised lawyer. The authorities, however, declined either to bail or discharge him, and he was kept in custody until he was sent a prisoner to England, to stand his trial.

An appeal of murder was brought against him, and a commission issued to try it. The case came on at the Old Bailey, in London, before Baron Burland, on the 11th December, 1776. The counsel for Roche declined in any way relying on the former acquittal at the Cape of Good Hope; and the case was again gone through. The fact of the killing was undisputed, but from the peculiar nature of the proceedings, there could not be, as in a common indictment for murder, a conviction for manslaughter; and the judge directed the jury, if they did not believe the killing to be malicious and deliberate, absolutely to acquit the prisoner. The jury brought in a verdict of acquittal.

An appeal of murder was brought against him, and a commission issued to try it. The case came on at the Old Bailey, in London, before Baron Burland, on the 11th December, 1776. The counsel for Roche declined in any way relying on the former acquittal at the Cape of Good Hope; and the case was again gone through. The fact of the killing was undisputed, but from the peculiar nature of the proceedings, there could not be, as in a common indictment for murder, a conviction for manslaughter; and the judge directed the jury, if they did not believe the killing to be malicious and deliberate, absolutely to acquit the prisoner. The jury brought in a verdict of acquittal.

The doubt about Roche's guilt arose on the following state of facts. On the evening of their arrival at the Cape, Ferguson and his friends were sitting at tea, at their lodgings, when a message was brought into the room; on hearing which Ferguson rose, went to his apartment, and, having put on his sword, and taken a loaded cane in his hand, went out. A friend named Grant followed him, and found Roche and him at the side of the house, round a corner, and heard the clash of swords, but refused to interfere. It was too dark to see what was occurring; but in a few moments he heard Roche going away, and Ferguson falling. Ferguson was carried in, and died immediately. All his wounds were in the left side.

The doubt about Roche's guilt arose on the following state of facts. On the evening of their arrival at the Cape, Ferguson and his friends were sitting at tea, at their lodgings, when a message was brought into the room; on hearing which Ferguson rose, went to his apartment, and, having put on his sword, and taken a loaded cane in his hand, went out. A friend named Grant followed him, and found Roche and him at the side of the house, round a corner, and heard the clash of swords, but refused to interfere. It was too dark to see what was occurring; but in a few moments he heard Roche going away, and Ferguson falling. Ferguson was carried in, and died immediately. All his wounds were in the left side.

The most violent vindictive feelings had existed between them; and there was proof of Roche's having threatened "to shorten the race of the Fergusons." The message, in answer to which Ferguson went out, was differently stated, being, according to one account, "Mr. Mathews wants Mr. Ferguson," and to the other, "a gentleman wants Mr. Mathews." The case for the prosecution was, that this message was a trap to draw Ferguson out of the house, and that on his going out, Roche attacked him; and this was confirmed by the improbability of Roche's going out for an innocent purpose, in a strange place, on the night of his landing, in the dark, and in the neighbourhood of Ferguson's lodgings; and particularly by the wounds being on the left side, which they could not be if given in a fair fight with small swords.

The most violent vindictive feelings had existed between them; and there was proof of Roche's having threatened "to shorten the race of the Fergusons." The message, in answer to which Ferguson went out, was differently stated, being, according to one account, "Mr. Mathews wants Mr. Ferguson," and to the other, "a gentleman wants Mr. Mathews." The case for the prosecution was, that this message was a trap to draw Ferguson out of the house, and that on his going out, Roche attacked him; and this was confirmed by the improbability of Roche's going out for an innocent purpose, in a strange place, on the night of his landing, in the dark, and in the neighbourhood of Ferguson's lodgings; and particularly by the wounds being on the left side, which they could not be if given in a fair fight with small swords.

Roche's account was, that on the evening of his arrival he went out to see the town, accompanied by a boy, a slave of his host; that they were watched by some person till they came near Ferguson's, when that person disappeared, and immediately afterwards, Roche was struck with a loaded stick on the head, knocked down, and his arm disabled; that afterwards he succeeded in rising, and, perceiving Ferguson, drew his sword, and after a struggle, in which he wished to avoid bloodshed, killed his assailant in self-defence. This was, to some extent, corroborated by the boy at the Dutch trial, and by a sailor in England, but both these witnesses were shaken a little in their testimony. According to this account, the message was a concerted signal to Ferguson, who had set a watch on Roche, intending to assassinate him. The locality of Ferguson's wounds was accounted for by his fighting both with cane and sword, using the former to parry. If the second version of the message was correct it would strongly confirm this account. There was no proof that Ferguson knew any one named Mathews.

Roche's account was, that on the evening of his arrival he went out to see the town, accompanied by a boy, a slave of his host; that they were watched by some person till they came near Ferguson's, when that person disappeared, and immediately afterwards, Roche was struck with a loaded stick on the head, knocked down, and his arm disabled; that afterwards he succeeded in rising, and, perceiving Ferguson, drew his sword, and after a struggle, in which he wished to avoid bloodshed, killed his assailant in self-defence. This was, to some extent, corroborated by the boy at the Dutch trial, and by a sailor in England, but both these witnesses were shaken a little in their testimony. According to this account, the message was a concerted signal to Ferguson, who had set a watch on Roche, intending to assassinate him. The locality of Ferguson's wounds was accounted for by his fighting both with cane and sword, using the former to parry. If the second version of the message was correct it would strongly confirm this account. There was no proof that Ferguson knew any one named Mathews.

It is not known what happened to Roche next, or where and when his life ended. At least one source claims he returned to India to die.

General Abercromby's force embarking for the

attack on Fort Ticonderoga

The Green Hills Of Tyrol

“there was a soldier, a Scottish Soldier”

The Green Hills Of Tyrol

There was a soldier, a Scottish soldier,

Who wandered far away and soldiered far away,

There was none bolder, with good broad shoulders,

He fought in many a fray and fought and won.

He's seen the glory, he's told the story,

Of battles glorious and deeds victorious.

But now he's sighing, his heart is crying,

To leave these green hills of Tyrol

There was a soldier, a Scottish soldier,

Who wandered far away and soldiered far away,

There was none bolder, with good broad shoulders,

He fought in many a fray and fought and won.

He's seen the glory, he's told the story,

Of battles glorious and deeds victorious.

But now he's sighing, his heart is crying,

To leave these green hills of Tyrol

Because these green hills are not Highland hills

Or the Island's hills, they're not my land's hills,

As fair as these green foreign hills may be

They are not the hills of home.

And now this soldier, this Scottish soldier,

Who wandered far away and soldiered far away,

Sees leaves are falling, and death is calling,

And he will fade away, on that dark land.

He called his piper, his trusty piper,

And bade him sound away, a pibroch sad to play,

Upon a hillside, a Scottish hillside

Not on these green hills of Tyrol

There was a soldier, a Scottish soldier,

Who wandered far away and soldiered far away,

There was none bolder, with good broad shoulders,

He fought in many a fray and fought and won.

He's seen the glory, he's told the story,

Of battles glorious and deeds victorious.

But now he's sighing, his heart is crying,

To leave these green hills of Tyrol.

And now this soldier, this Scottish soldier,

Who wanders far no more, and soldiers far no more,

Now on a hillside, a Scottish hillside,

You'll see a piper play this soldier home.

He's seen the glory, he's told the story,

Of battles glorious, and deeds victorious;

But he will cease now, he is at peace now,

Far from these green hills of Tyrol

There was a soldier, a Scottish soldier,

Who wandered far away and soldiered far away,

There was none bolder, with good broad shoulders,

He fought in many a fray and fought and won.

He's seen the glory, he's told the story,

Of battles glorious and deeds victorious.

But now he's sighing, his heart is crying,

To leave these green hills of Tyrol.

‘Welsh National Costume’ is relatively young and not as famous as ‘Scottish National Costume’. Still, the Welsh do have a national costume, but it’s the way the ladies dress that is most well known, in fact there isn’t really a national costume for men … although recently, through the rise of nationalism in Wales, a tartan has been created and tartan trousers or kilts are often worn.

‘Welsh National Costume’ is relatively young and not as famous as ‘Scottish National Costume’. Still, the Welsh do have a national costume, but it’s the way the ladies dress that is most well known, in fact there isn’t really a national costume for men … although recently, through the rise of nationalism in Wales, a tartan has been created and tartan trousers or kilts are often worn.

One style of costume was much more marketable than the different styles that were actually worn at the time. The costume we know today has much to do with artists and, later, photographers keen to encourage a stereotypical national costume to help boost their trade within a burgeoning tourist industry.

One style of costume was much more marketable than the different styles that were actually worn at the time. The costume we know today has much to do with artists and, later, photographers keen to encourage a stereotypical national costume to help boost their trade within a burgeoning tourist industry.

The costume we typically identify with

The costume we typically identify with

Wales is based on clothing worn by the

Wales is based on clothing worn by the

Welsh countrywomen in the ealy 1800s, which was a striped flannel petticoat, worn under a open-fronted bedgown made of wool with a black and white check pattern, with a starched white apron, a red flannel shawl and kerchief or cap. The style of bedgown varied, with loose coat-like gowns, gowns with a fitted bodice and long skirts and also the short gown, which was very similar to a riding habit style. The hats generally worn were the same as hats worn by men at the period. The tall ‘chimney’ hat did not appear until the late 1840s and seems to be based on an amalgamation of men’s top hats and a form of high hat worn during the 1790-1820 period in country areas of Wales … it is made of black felt, with a high crown and wide brim, which is worn over a lace cap. Proper Welsh ladies always wore black woolen stockings and black shoes and carried a basket, made from willow withies.

Welsh countrywomen in the ealy 1800s, which was a striped flannel petticoat, worn under a open-fronted bedgown made of wool with a black and white check pattern, with a starched white apron, a red flannel shawl and kerchief or cap. The style of bedgown varied, with loose coat-like gowns, gowns with a fitted bodice and long skirts and also the short gown, which was very similar to a riding habit style. The hats generally worn were the same as hats worn by men at the period. The tall ‘chimney’ hat did not appear until the late 1840s and seems to be based on an amalgamation of men’s top hats and a form of high hat worn during the 1790-1820 period in country areas of Wales … it is made of black felt, with a high crown and wide brim, which is worn over a lace cap. Proper Welsh ladies always wore black woolen stockings and black shoes and carried a basket, made from willow withies.

Shawls were the most fashionable of accessories between 1840 and 1870. The most popular were the Paisley shawls whose pattern originally came from Kashmir in India.

Shawls were the most fashionable of accessories between 1840 and 1870. The most popular were the Paisley shawls whose pattern originally came from Kashmir in India.

At first plain shawls with a woven patterned border attached were the most common. Later many fine examples with all-over and border patterns were woven in Norfolk, Scotland and Paris. Shawls of the middle of the century were very large and complemented the full skirts of the period. Shawls were made in other fabrics and patterns, including Cantonese silk and fine machine lace, though it was the paisley pattern which became very popular in Wales along with home-produced woollen shawls with checked patterns.

At first plain shawls with a woven patterned border attached were the most common. Later many fine examples with all-over and border patterns were woven in Norfolk, Scotland and Paris. Shawls of the middle of the century were very large and complemented the full skirts of the period. Shawls were made in other fabrics and patterns, including Cantonese silk and fine machine lace, though it was the paisley pattern which became very popular in Wales along with home-produced woollen shawls with checked patterns.

In later years, although fashionable women no longer wore shawls, smaller shawls were still made and worn by countrywomen and working women in the towns. By the 1870s, cheaper shawls were produced by printing the designs on fine wools or cotton. Even during the early years of the twentieth century woollen, knitted and paisley shawls were widely worn in rural Wales. The paisley shawl even became accepted as part of 'Welsh' costume, though there is nothing traditionally Welsh about it at all.

In later years, although fashionable women no longer wore shawls, smaller shawls were still made and worn by countrywomen and working women in the towns. By the 1870s, cheaper shawls were produced by printing the designs on fine wools or cotton. Even during the early years of the twentieth century woollen, knitted and paisley shawls were widely worn in rural Wales. The paisley shawl even became accepted as part of 'Welsh' costume, though there is nothing traditionally Welsh about it at all.

One tradition of shawl wearing which is truly Welsh is the practice of carrying babies in a shawl. Illustrations showing this have survived from the late eighteenth century when Welsh women wore a simple length of cloth wrapped around their body. When shawls became popular, they were adapted to the same use, and some women even today still keep up the tradition

One tradition of shawl wearing which is truly Welsh is the practice of carrying babies in a shawl. Illustrations showing this have survived from the late eighteenth century when Welsh women wore a simple length of cloth wrapped around their body. When shawls became popular, they were adapted to the same use, and some women even today still keep up the tradition

Although Lady Llanover created ‘a weird and wonderful’ costume made for her court harpist, she was not particularly concerned with a national costume for men.

Although Lady Llanover created ‘a weird and wonderful’ costume made for her court harpist, she was not particularly concerned with a national costume for men.

As a result, Welsh men do not have a national dress, although attempts have been made in recent decades to ‘revive’ a Welsh kilt which never in fact existed!

As a result, Welsh men do not have a national dress, although attempts have been made in recent decades to ‘revive’ a Welsh kilt which never in fact existed!

Even in Scotland, there is evidence to show that the kilt as we know it today … a national costume that has, in recent times, been enthusiastically embraced by both lowlander and highlander alike … is a comparatively modern development from the belted plaid, which was a more substantial garment worn across the shoulder. (And which, in olden times, was only worn by the Gaelic-speaking highlanders and islanders, who were in those days so despised by the relatively wealthy and influential lowlanders.)

Even in Scotland, there is evidence to show that the kilt as we know it today … a national costume that has, in recent times, been enthusiastically embraced by both lowlander and highlander alike … is a comparatively modern development from the belted plaid, which was a more substantial garment worn across the shoulder. (And which, in olden times, was only worn by the Gaelic-speaking highlanders and islanders, who were in those days so despised by the relatively wealthy and influential lowlanders.)

The current concept of ‘Welsh National Costume’ is largely the result of one woman’s efforts to preserve and popularise a sense of Welsh national identity. Augusta Hall, later Lady Llanover was what nowadays would be called an ‘activist’.

The current concept of ‘Welsh National Costume’ is largely the result of one woman’s efforts to preserve and popularise a sense of Welsh national identity. Augusta Hall, later Lady Llanover was what nowadays would be called an ‘activist’.

She was born at Ty Uchaf on the 21st of March 1802 - the youngest daughter of Benjamin and Georgina Waddington, who had moved to Llanover (in Wales) from Nottingham (in England) in 1792. In December 1823, Augusta married Benjamin Hall (1802 – 1867) of Abercarn, an iron merchant. He was created a baronet in 1838. He was a Member of Parliament for 22 years until 1859, when he was raised to the peerage as a Baron. Whilst in London, Benjamin Hall was appointed Commissioner for Works, but he did not forget his allegiance to Wales and he fought for Welsh cultural interests, such as upholding in Parliament the right of the Welsh to have the services of the Church ’rendered in their own tongue…’, and insisting that any new Bishop should be Welsh-speaking and live in Wales.

In 1828, Sir Benjamin and Lady Hall commissioned Thomas Hopper to design a house. They intended their new home, known as Llanover House, to become the recognised centre of all their activities, particularly the promotion of the Welsh language and culture.

In 1828, Sir Benjamin and Lady Hall commissioned Thomas Hopper to design a house. They intended their new home, known as Llanover House, to become the recognised centre of all their activities, particularly the promotion of the Welsh language and culture.

Lady Llanover ensured that each of the properties on the estate had Welsh names, and required all her tenants and estate workers to speak Welsh. As it became increasingly difficult to find local Welsh speakers, Lady Llanover encouraged people for whom Welsh was their first language to move from Cardiganshire to Monmouthshire.

Lady Llanover ensured that each of the properties on the estate had Welsh names, and required all her tenants and estate workers to speak Welsh. As it became increasingly difficult to find local Welsh speakers, Lady Llanover encouraged people for whom Welsh was their first language to move from Cardiganshire to Monmouthshire.

Lady Llanover’s House Harpist in ‘national costume’ that she ‘invented’ for him

She wanted her home – Llanover House – to become known for the promotion of Welsh language and culture.

She wanted her home – Llanover House – to become known for the promotion of Welsh language and culture.

She believed in the importance of a ‘national identity’ for the Welsh, and saw the wearing of a national costume as a way of promoting Wales and keeping alive the traditional values of Welsh culture that were under threat at the time.

She believed in the importance of a ‘national identity’ for the Welsh, and saw the wearing of a national costume as a way of promoting Wales and keeping alive the traditional values of Welsh culture that were under threat at the time.

Some even argue that she completely ‘invented’ the current concept of Welsh National clothing, with no accurate basis:

Some even argue that she completely ‘invented’ the current concept of Welsh National clothing, with no accurate basis:

“Lady Llanover ruthlessly inflicted her new fad on all and sundry” (H.M.Vaughan – South Wales Squires)

There is no denying that she was a talented ‘publicist’ - she made her estate workers, tenants and guests wear a ‘uniform’ based on her ideas of national dress … which was not universally popular, for her maids changed out of them at the first opportunity for a more fashionable dress when they left the estate!

There is no denying that she was a talented ‘publicist’ - she made her estate workers, tenants and guests wear a ‘uniform’ based on her ideas of national dress … which was not universally popular, for her maids changed out of them at the first opportunity for a more fashionable dress when they left the estate!

To be fair to Lady Llanover, one of her main aims was to popularise and support the native woollen industry in Wales, and she built a woolen mill in the grounds of Llanover House.

To be fair to Lady Llanover, one of her main aims was to popularise and support the native woollen industry in Wales, and she built a woolen mill in the grounds of Llanover House.

There was also the beginnings of mass tourism … and the concept of ‘quaint’ as a tourist ‘trap’ is not a modern one! Several researchers have suggested that this was the main driver for the popularisation of a Welsh National Costume.

There was also the beginnings of mass tourism … and the concept of ‘quaint’ as a tourist ‘trap’ is not a modern one! Several researchers have suggested that this was the main driver for the popularisation of a Welsh National Costume.

Lady Llanover died in 1896 having outlived her husband by 29 years. She is buried alongside him at St Bartholomew's Church in Wales, Llanover.

Lady Llanover died in 1896 having outlived her husband by 29 years. She is buried alongside him at St Bartholomew's Church in Wales, Llanover.

Lady Llanover’s interest in Welsh culture was extensive, and there are many examples of her influence.

Lady Llanover’s interest in Welsh culture was extensive, and there are many examples of her influence.

For example, the close association of the harp with dance had made it offensive to puritanical ‘non–conformists’ (Methodists, Presbyterians, etc) and, by the 19th century, the triple harp, in particular, had become scarce. Lady Llanover was without doubt the most important figure in the survival and consequent revival of interest in the triple harp and its Welsh traditions. Lady Llanover gave permanent employment at Llanover House to Welsh players of the triple harp.

For example, the close association of the harp with dance had made it offensive to puritanical ‘non–conformists’ (Methodists, Presbyterians, etc) and, by the 19th century, the triple harp, in particular, had become scarce. Lady Llanover was without doubt the most important figure in the survival and consequent revival of interest in the triple harp and its Welsh traditions. Lady Llanover gave permanent employment at Llanover House to Welsh players of the triple harp.

Lady Llanover also collected Welsh folk music and encouraged others to do so, particularly Maria Jane Williams (1795 – 1873), whose collection ‘The Ancient Airs of Gwent & Morgannwg’ won the prize in the 1837 Eisteddfod. This collection was published with Lady Llanover’s help in 1844. She also encouraged others including Bassett Jones of Cardiff, Abraham Jeremiah and Elias Francis both of Llanover to manufacture harps, some of which she donated, or persuaded her friends to donate, as prizes in the Cymreigyddion Eisteddfodau held in Abergavenny. Lady Llanover invited noted composers and Welsh musicians to stay and perform at Llanover House.

Lady Llanover also collected Welsh folk music and encouraged others to do so, particularly Maria Jane Williams (1795 – 1873), whose collection ‘The Ancient Airs of Gwent & Morgannwg’ won the prize in the 1837 Eisteddfod. This collection was published with Lady Llanover’s help in 1844. She also encouraged others including Bassett Jones of Cardiff, Abraham Jeremiah and Elias Francis both of Llanover to manufacture harps, some of which she donated, or persuaded her friends to donate, as prizes in the Cymreigyddion Eisteddfodau held in Abergavenny. Lady Llanover invited noted composers and Welsh musicians to stay and perform at Llanover House.

From 1826, when Lady Llanover first attended an eisteddfod at Brecon and met Carnhuanawc (the Revd. Thomas Price), she both sponsored and entered competitions. At the Eisteddfod held at Cardiff in 1834, she won the prize for an essay entitled ‘The Advantages resulting from the Preservation of the Welsh language and National Costume of Wales’. Her nom-de-plume on this occasion was Gwenynen Gwent (the Bee of Gwent), the bardic name by which she subsequently became known throughout Wales. From 1834-1853 she was the inspirational force behind the famous Eisteddfodau held in Abergavenny by the Cymreigyddion Society.

From 1826, when Lady Llanover first attended an eisteddfod at Brecon and met Carnhuanawc (the Revd. Thomas Price), she both sponsored and entered competitions. At the Eisteddfod held at Cardiff in 1834, she won the prize for an essay entitled ‘The Advantages resulting from the Preservation of the Welsh language and National Costume of Wales’. Her nom-de-plume on this occasion was Gwenynen Gwent (the Bee of Gwent), the bardic name by which she subsequently became known throughout Wales. From 1834-1853 she was the inspirational force behind the famous Eisteddfodau held in Abergavenny by the Cymreigyddion Society.

Lady Llanover’s legacy can still be seen all over ‘Welsh-Wales’ each year, on the 1st of March, when thousands of schoolgirls don the Welsh national costume as part of the annual celebrations for the Welsh national day … St David’s Day.

Lady Llanover’s legacy can still be seen all over ‘Welsh-Wales’ each year, on the 1st of March, when thousands of schoolgirls don the Welsh national costume as part of the annual celebrations for the Welsh national day … St David’s Day.

Steeplechasing – Ireland’s National Sport

Steeplechasing is an exciting winter racing spectacle, rich in the traditions of all the bold riding for which old Ireland was, and still is, so renowned. It is interesting to note that jumps racing is Ireland’s national sport - the Irish, renowned horse lovers, have more jumps races than flat races. (Even England has more than 500 all-jumps race meetings a year.)

Steeplechasing is an exciting winter racing spectacle, rich in the traditions of all the bold riding for which old Ireland was, and still is, so renowned. It is interesting to note that jumps racing is Ireland’s national sport - the Irish, renowned horse lovers, have more jumps races than flat races. (Even England has more than 500 all-jumps race meetings a year.)

Steeplechasing was ‘born’ in County Cork, Ireland in 1752. Two gentlemen farmers, Cornelius O’Callaghan and Edmund Blake, after returning from fox hunting settled an argument over who owned the best horse and rode for a bet over walls and cross-country. The start and finish of their 4 ½ miles course was marked by the steeples of St. John’s church at Buttevant and St. Mary’s church at Doneraile. The winner actually rode right through the church while the padre was conducting a funeral!

Steeplechasing was ‘born’ in County Cork, Ireland in 1752. Two gentlemen farmers, Cornelius O’Callaghan and Edmund Blake, after returning from fox hunting settled an argument over who owned the best horse and rode for a bet over walls and cross-country. The start and finish of their 4 ½ miles course was marked by the steeples of St. John’s church at Buttevant and St. Mary’s church at Doneraile. The winner actually rode right through the church while the padre was conducting a funeral!

Soon steeplechase racing spread from Ireland to England, where in 1792, England’s first recorded steeplechase race was held. From Ireland and England the sport of steeplechasing has spread all over the world.

Soon steeplechase racing spread from Ireland to England, where in 1792, England’s first recorded steeplechase race was held. From Ireland and England the sport of steeplechasing has spread all over the world.