The Noble Society of Celts, is an hereditary society of persons with Celtic roots and

interests, who are of noble title and gentle birth, and who

have come together in a search for, and celebration of, things Celtic.

"Spring 2011"

Tam O'Shanter

Tam o' Shanter is about an old Scottish legend. It is a wonderful, epic poem in which the famous Scottish bard Robert Burns paints a vivid picture of the drinking classes in the old Scotch town of Ayr in 1790. This story is about a farmer called Tam O'Shanter. It is populated by several unforgettable characters including of course Tam himself, his bosom pal, Souter (Cobbler) Johnnie and his own long suffering wife Kate, "Gathering her brows like gathering storm, nursing her wrath to keep it warm". We are also introduced to Kirkton Jean, the ghostly, "winsome wench", Cutty Sark and let's not forget his gallant horse, Maggie.

The tale includes humour, pathos, horror, social comment and in my opinion some of the most beautiful lines that Burns ever penned. For example, "But pleasures are like poppies spread, You sieze the flower, its bloom is shed; Or like the snow falls in the river, A moment white--then melts for ever".

It was very late on a dark and stormy night when Tam, who had been to Market to sell his wares and had called at the local inn afterwards for a few drinks, began his journey home. Tam was riding his old mare Meg down a lonely road, when he drew close to the church at Kirk Alloway.

Through the cold night air he heard a strange and scary sound, and as he looked into the night sky he saw the glare of fire!

There, in the churchyard, dancing around a huge bonfire was a coven of witches and warlocks. Tam sat on his horse, rigid with terror! The witches danced on and Tam noticed that one of the hags was younger and more beautiful than the others. Her name was Nannie, but Tam didn't know this; all she was wearing was a short petticoat so he called her 'cutty sark', which is an old regional Scottish name for this garment.

Well, the dancing became wilder and wilder and Tam became more and more engrossed. At last, he could bear the suspense no longer and he shouted out,

"Weel done 'cutty sark'!"

With a flash the bonfire went out, and a soul-tearing howl went up from the witches and warlocks, as they began to race towards Tam, desperate to get to this mortal who had ruined their revelry.

Poor Tam. He was in fear of his life, and for a moment just sat there, but after a few seconds that seemed like lifetimes, he managed to spur Meg on, in a desperate race to save his life.

Now, witches cannot cross running water, and fortunately for Tam, the river Doon was nearby. He set Meg galloping madly towards the bridge, with the witches in hot pursuit.

Nannie, being younger and faster than the rest, was the closest to him, and was reaching out to grab Meg’s tail, just as the mare reached the bridge.

Luckily for Tam (although not so for Meg), the horse's tail came away in Nannie's hand just as the mare galloped over the bridge. Tam was saved! The witches and warlocks stood on the river-bank cursing and screaming at Tam who had had a very narrow escape.

This was the story that inspired the naming of ‘Cutty Sark’ (the famous British square-rigger ‘clipper’ ship that broke so many sailing records bring tea to Britain from China). Although we do not know why the name was chosen, Jock Willis was a well-read man who enjoyed poetry. During his time as a ship's captain, he would read French novels in his cabin. He also named one of his other ships the Hallowe'en, the title of another Burns poem. Although "cutty sark" was a little unusual, it certainly suits a sleek, swift tea clipper, giving her an air of magic and mystery.

Enjoy "Tam o' Shanter - a Tale"

“Tam O’Shanter” painted by Abraham Cooper 1814

Tam o' Shanter (Translation)

When the peddler people leave the streets,

And thirsty neighbours, neighbours meet;

As market days are wearing late,

And folk begin to take the road home,

While we sit boozing strong ale,

And getting drunk and very happy,

We don’t think of the long Scots miles,

The marshes, waters, steps and stiles,

That lie between us and our home,

Where sits our sulky, sullen dame (wife),

Gathering her brows like a gathering storm,

Nursing her wrath, to keep it warm.

This truth finds honest Tam o' Shanter,

As he from Ayr one night did canter;

Old Ayr, which never a town surpasses,

For honest men and bonny lasses.

Oh Tam, had you but been so wise,

As to have taken your own wife Kate’s advice!

She told you well you were a waster,

A rambling, blustering, drunken boaster,

That from November until October,

Each market day you were not sober;

During each milling period with the miller,

You sat as long as you had money,

For every horse he put a shoe on,

The blacksmith and you got roaring drunk on;

That at the Lords House, even on Sunday,

You drank with Kirkton Jean till Monday.

She prophesied, that, late or soon,

You would be found deep drowned in Doon,

Or caught by warlocks in the murk,

By Alloway’s old haunted church.

Ah, gentle ladies, it makes me cry,

To think how many counsels sweet,

How much long and wise advice

The husband from the wife despises!

But to our tale :- One market night,

Tam was seated just right,

Next to a fireplace, blazing finely,

With creamy ales, that drank divinely;

And at his elbow, Cobbler Johnny,

His ancient, trusted, thirsty crony;

Tom loved him like a very brother,

They had been drunk for weeks together.

The night drove on with songs and clatter,

And every ale was tasting better;

The landlady and Tam grew gracious,

With secret favours, sweet and precious;

The cobbler told his queerest stories;

The landlord’s laugh was ready chorus:

Outside, the storm might roar and rustle,

Tam did not mind the storm a whistle.

Care, mad to see a man so happy,

Even drowned himself in ale.

As bees fly home with loads of treasure,

The minutes winged their way with pleasure:

Kings may be blessed, but Tam was glorious,

Over all the ills of life victorious.

But pleasures are like poppies spread:

You seize the flower, its bloom is shed;

Or like the snow fall on the river,

A moment white - then melts forever,

Or like the Aurora Borealis rays,

That move before you can point to where they're placed;

Or like the rainbow’s lovely form,

Vanishing amid the storm.

No man can tether time or tide,

The hour approaches Tom must ride:

That hour, of night’s black arch - the key-stone,

That dreary hour he mounts his beast in

And such a night he takes to the road in

As never a poor sinner had been out in.

The wind blew as if it had blown its last;

The rattling showers rose on the blast;

The speedy gleams the darkness swallowed,

Loud, deep and long the thunder bellowed:

That night, a child might understand,

The Devil had business on his hand.

Well mounted on his grey mare, Meg.

A better never lifted leg,

Tom, raced on through mud and mire,

Despising wind and rain and fire;

Whilst holding fast his good blue bonnet,

While crooning over some old Scots sonnet,

Whilst glowering round with prudent care,

Lest ghosts catch him unaware:

Alloway’s Church was drawing near,

Where ghosts and owls nightly cry.

By this time he was across the ford,

Where in the snow the pedlar got smothered;

And past the birch trees and the huge stone,

Where drunken Charlie broke his neck bone;

And through the thorns, and past the monument,

Where hunters found the murdered child;

And near the thorn, above the well,

Where Mungo’s mother hung herself.

Before him the river Doon pours all his floods;

The doubling storm roars throught the woods;

The lightnings flashes from pole to pole;

Nearer and more near the thunder rolls;

When, glimmering through the groaning trees,

Alloway’s Church seemed in a blaze,

Through every gap , light beams were glancing,

And loud resounded mirth and dancing.

Inspiring, bold John Barleycorn! (whisky)

What dangers you can make us scorn!

With ale, we fear no evil;

With whisky, we’ll face the Devil!

The ales so swam in Tam’s head,

Fair play, he didn’t care a farthing for devils.

But Maggie stood, right sore astonished,

Till, by the heel and hand admonished,

She ventured forward on the light;

And, vow! Tom saw an incredible sight!

Warlocks and witches in a dance:

No cotillion, brand new from France,

But hornpipes, jigs, strathspeys, and reels,

Put life and mettle in their heels.

In a window alcove in the east,

There sat Old Nick, in shape of beast;

A shaggy dog, black, grim, and large,

To give them music was his charge:

He screwed the pipes and made them squeal,

Till roof and rafters all did ring.

Coffins stood round, like open presses,

That showed the dead in their last dresses;

And, by some devilish magic sleight,

Each in its cold hand held a light:

By which heroic Tom was able

To note upon the holy table,

A murderer’s bones, in gibbet-irons;

Two span-long, small, unchristened babies;

A thief just cut from his hanging rope -

With his last gasp his mouth did gape;

Five tomahawks with blood red-rusted;

Five scimitars with murder crusted;

A garter with which a baby had strangled;

A knife a father’s throat had mangled -

Whom his own son of life bereft -

The grey-hairs yet stack to the shaft;

With more o' horrible and awful,

Which even to name would be unlawful.

Three Lawyers’ tongues, turned inside out,

Sown with lies like a beggar’s cloth -

Three Priests’ hearts, rotten, black as muck

Lay stinking, vile, in every nook.

As Thomas glowered, amazed, and curious,

The mirth and fun grew fast and furious;

The piper loud and louder blew,

The dancers quick and quicker flew,

They reeled, they set, they crossed, they linked,

Till every witch sweated and smelled,

And cast her ragged clothes to the floor,

And danced deftly at it in her underskirts!

Now Tam, O Tam! had these been queens,

All plump and strapping in their teens!

Their underskirts, instead of greasy flannel,

Been snow-white seventeen hundred linen! -

The trousers of mine, my only pair,

That once were plush, of good blue hair,

I would have given them off my buttocks

For one blink of those pretty girls !

But withered hags, old and droll,

Ugly enough to suckle a foal,

Leaping and flinging on a stick,

Its a wonder it didn’t turn your stomach!

But Tam knew what was what well enough:

There was one winsome, jolly wench,

That night enlisted in the core,

Long after known on Carrick shore

(For many a beast to dead she shot,

And perished many a bonnie boat,

And shook both much corn and barley,

And kept the country-side in fear.)

Her short underskirt, o’ Paisley cloth,

That while a young lass she had worn,

In longitude though very limited,

It was her best, and she was proud. . .

Ah! little knew your reverend grandmother,

That skirt she bought for her little grandaughter,

With two Scots pounds (it was all her riches),

Would ever graced a dance of witches!

But here my tale must stoop and bow,

Such words are far beyond her power;

To sing how Nannie leaped and kicked

(A supple youth she was, and strong);

And how Tom stood like one bewitched,

And thought his very eyes enriched;

Even Satan glowered, and fidgeted full of lust,

And jerked and blew with might and main;

Till first one caper, then another,

Tom lost his reason all together,

And roars out: ‘ Well done, short skirt! ’

And in an instant all was dark;

And scarcely had he Maggie rallied,

When out the hellish legion sallied.

As bees buzz out with angry wrath,

When plundering herds assail their hive;

As a wild hare’s mortal foes,

When, pop! she starts running before their nose;

As eager runs the market-crowd,

When ‘ Catch the thief! ’ resounds aloud:

So Maggie runs, the witches follow,

With many an unearthly scream and holler.

Ah, Tom! Ah, Tom! You will get what's coming!

In hell they will roast you like a herring!

In vain your Kate awaits your coming !

Kate soon will be a woeful woman!

Now, do your speedy utmost, Meg,

And beat them to the key-stone of the bridge;

There, you may toss your tale at them,

A running stream they dare not cross!

But before the key-stone she could make,

She had to shake a tail at the fiend;

For Nannie, far before the rest,

Hard upon noble Maggie pressed,

And flew at Tam with furious aim;

But little was she Maggie’s mettle!

One spring brought off her master whole,

But left behind her own grey tail:

The witch caught her by the rump,

And left poor Maggie scarce a stump.

Now, who this tale of truth shall read,

Each man, and mother’s son, take heed:

Whenever to drink you are inclined,

Or short skirts run in your mind,

Think! you may buy joys over dear:

Remember Tam o’ Shanter’s mare.

Tam o' Shanter (Original)

When chapmen billies leave the street,

And drouthy neibors, neibors meet,

As market days are wearing late,

An' folk begin to tak the gate;

While we sit bousing at the nappy,

And getting fou and unco happy,

We think na on the lang Scots miles,

The mosses, waters, slaps, and styles,

That lie between us and our hame,

Where sits our sulky sullen dame.

Gathering her brows like gathering storm,

Nursing her wrath to keep it warm.

This truth fand honest Tam o' Shanter,

As he frae Ayr ae night did canter,

(Auld Ayr, wham ne'er a town surpasses

For honest men and bonie lasses.)

O Tam! had'st thou but been sae wise,

As ta'en thy ain wife Kate's advice!

She tauld thee weel thou was a skellum,

A blethering, blustering, drunken blellum;

That frae November till October,

Ae market-day thou was nae sober;

That ilka melder, wi' the miller,

Thou sat as lang as thou had siller;

That every naig was ca'd a shoe on,

The smith and thee gat roaring fou on;

That at the Lord's house, even on Sunday,

Thou drank wi' Kirkton Jean till Monday.

She prophesied that late or soon,

Thou would be found deep drown'd in Doon;

Or catch'd wi' warlocks in the mirk,

By Alloway's auld haunted kirk.

Ah, gentle dames! it gars me greet,

To think how mony counsels sweet,

How mony lengthen'd, sage advices,

The husband frae the wife despises!

But to our tale:-- Ae market-night,

Tam had got planted unco right;

Fast by an ingle, bleezing finely,

Wi' reaming swats, that drank divinely

And at his elbow, Souter Johnny,

His ancient, trusty, drouthy crony;

Tam lo'ed him like a vera brither--

They had been fou for weeks thegither!

The night drave on wi' sangs and clatter

And ay the ale was growing better:

The landlady and Tam grew gracious,

wi' favours secret,sweet and precious

The Souter tauld his queerest stories;

The landlord's laugh was ready chorus:

The storm without might rair and rustle,

Tam did na mind the storm a whistle.

Care, mad to see a man sae happy,

E'en drown'd himsel' amang the nappy!

As bees flee hame wi' lades o' treasure,

The minutes wing'd their way wi' pleasure:

Kings may be blest, but Tam was glorious.

O'er a' the ills o' life victorious!

But pleasures are like poppies spread,

You sieze the flower, its bloom is shed;

Or like the snow falls in the river,

A moment white--then melts for ever;

Or like the borealis race,

That flit ere you can point their place;

Or like the rainbow's lovely form

Evanishing amid the storm.--

Nae man can tether time or tide;

The hour approaches Tam maun ride;

That hour, o' night's black arch the key-stane,

That dreary hour he mounts his beast in;

And sic a night he taks the road in

As ne'er poor sinner was abroad in.

The wind blew as 'twad blawn its last;

The rattling showers rose on the blast;

The speedy gleams the darkness swallow'd

Loud, deep, and lang, the thunder bellow'd:

That night, a child might understand,

The Deil had business on his hand.

Weel mounted on his gray mare, Meg--

A better never lifted leg--

Tam skelpit on thro' dub and mire;

Despisin' wind and rain and fire.

Whiles holding fast his gude blue bonnet;

Whiles crooning o'er some auld Scots sonnet;

Whiles glowring round wi' prudent cares,

Lest bogles catch him unawares:

Kirk-Alloway was drawing nigh,

Whare ghaists and houlets nightly cry.

By this time he was cross the ford,

Whare, in the snaw, the chapman smoor'd;

And past the birks and meikle stane,

Whare drunken Chairlie brak 's neck-bane;

And thro' the whins, and by the cairn,

Whare hunters fand the murder'd bairn;

And near the thorn, aboon the well,

Whare Mungo's mither hang'd hersel'.--

Before him Doon pours all his floods;

The doubling storm roars thro' the woods;

The lightnings flash from pole to pole;

Near and more near the thunders roll:

When, glimmering thro' the groaning trees,

Kirk-Alloway seem'd in a bleeze;

Thro' ilka bore the beams were glancing;

And loud resounded mirth and dancing.

Inspiring bold John Barleycorn!

What dangers thou canst make us scorn!

Wi' tippeny, we fear nae evil;

Wi' usquabae, we'll face the devil!--

The swats sae ream'd in Tammie's noddle,

Fair play, he car'd na deils a boddle.

But Maggie stood, right sair astonish'd,

Till, by the heel and hand admonish'd,

She ventured forward on the light;

And, vow! Tam saw an unco sight

Warlocks and witches in a dance;

Nae cotillion brent-new frae France,

But hornpipes, jigs strathspeys, and reels,

Put life and mettle in their heels.

A winnock-bunker in the east,

There sat auld Nick, in shape o' beast;

A towzie tyke, black, grim, and large,

To gie them music was his charge:

He scre'd the pipes and gart them skirl,

Till roof and rafters a' did dirl.--

Coffins stood round, like open presses,

That shaw'd the dead in their last dresses;

And by some develish cantraip slight,

Each in its cauld hand held a light.--

By which heroic Tam was able

To note upon the haly table,

A murders's banes in gibbet-airns;

Twa span-lang, wee, unchristen'd bairns;

A thief, new-cutted frae a rape,

Wi' his last gasp his gab did gape;

Five tomahawks, wi blude red-rusted;

Five scymitars, wi' murder crusted;

A garter, which a babe had strangled;

A knife, a father's throat had mangled,

Whom his ain son o' life bereft,

The gray hairs yet stack to the heft;

Wi' mair o' horrible and awfu',

Which even to name was be unlawfu'.

Three lawyers' tongues, turn'd inside out,

Wi' lies seam'd like a beggar's clout;

Three priests' hearts, rotten, black as muck,

Lay stinking, vile in every neuk.

As Tammie glowr'd, amaz'd, and curious,

The mirth and fun grew fast and furious;

The piper loud and louder blew;

The dancers quick and quicker flew;

They reel'd, they set, they cross'd, they cleekit,

Till ilka carlin swat and reekit,

And coost her duddies to the wark,

And linket at it her sark!

Now Tam, O Tam! had thae been queans,

A' plump and strapping in their teens,

Their sarks, instead o' creeshie flannen,

Been snaw-white seventeen hunder linnen!

Thir breeks o' mine, my only pair,

That ance were plush, o' gude blue hair,

I wad hae gi'en them off my hurdies,

For ae blink o' the bonie burdies!

But wither'd beldams, auld and droll,

Rigwoodie hags wad spean a foal,

Louping and flinging on a crummock,

I wonder did na turn thy stomach!

But Tam kend what was what fu' brawlie:

There was ae winsome wench and waulie,

That night enlisted in the core,

Lang after ken'd on Carrick shore;

(For mony a beast to dead she shot,

And perish'd mony a bonie boat,

And shook baith meikle corn and bear,

And kept the country-side in fear.)

Her cutty-sark, o' Paisley harn

That while a lassie she had worn,

In longitude tho' sorely scanty,

It was her best, and she was vauntie,-

Ah! little ken'd thy reverend grannie,

That sark she coft for he wee Nannie,

Wi' twa pund Scots, ('twas a' her riches),

Wad ever grac'd a dance of witches!

But here my Muse her wing maun cour;

Sic flights are far beyond her pow'r;

To sing how Nannie lap and flang,

(A souple jade she was, and strang),

And how Tam stood, like ane bewitch'd,

And thought his very een enrich'd;

Even Satan glowr'd, and fidg'd fu' fain,

And hotch'd and blew wi' might and main;

Till first ae caper, syne anither,

Tam tint his reason ' thegither,

And roars out, "Weel done, Cutty-sark!"

And in an instant all was dark:

And scarcely had he Maggie rallied,

When out the hellish legion sallied.

As bees bizz out wi' angry fyke,

When plundering herds assail their byke;

As open pussie's mortal foes,

When, pop! she starts before their nose;

As eager runs the market-crowd,

When "Catch the thief!" resounds aloud;

So Maggie runs, the witches follow,

Wi' mony an eldritch skriech and hollo.

Ah, Tam! ah, Tam! thou'll get thy fairin'!

In hell they'll roast thee like a herrin'!

In vain thy Kate awaits thy commin'!

Kate soon will be a woefu' woman!

Now, do thy speedy utmost, Meg,

And win the key-stane o' the brig;

There at them thou thy tail may toss,

A running stream they dare na cross.

But ere the key-stane she could make,

The fient a tail she had to shake!

For Nannie, far before the rest,

Hard upon noble Maggie prest,

And flew at Tam wi' furious ettle;

But little wist she Maggie's mettle -

Ae spring brought off her master hale,

But left behind her ain gray tail;

The carlin claught her by the rump,

And left poor Maggie scarce a stump.

No, wha this tale o' truth shall read,

Ilk man and mother's son take heed;

Whene'er to drink you are inclin'd,

Or cutty-sarks run in your mind,

Think! ye may buy joys o'er dear -

Remember Tam o' Shanter's mare.

”Tam O'Shanter” - Royal Doulton, 1973 – 1980

This is the poem of which the author, in a letter to Mrs. Dunlop, dated April 1791, announcing the birth of his third son, William Nicol Burns, remarked as follows:- "On Saturday morning last, Mrs Burns made me a present of a fine boy - rather stouter, but not so handsome as your godson was at his time of life. Indeed, I look on your little namesakes to be my chef d'oeuvre in that species of manufacture, as I look on Tam o' Shanter to be my standard performance in the poetical line. "Tis true, both the one and the other discover a spice of roguish waggery, that might perhaps be as well spared; but then they also shew, in my opinion, a force of genius, and a finishing polish, that I despair of ever excelling."

"A finishing polish!" - This is one characteristic of the poem which from Cromek's time downwards, we have been told, on the authority of Mrs. Burns, "was the work of one day." - "One day between breakfast and dinner," according to some annotators; and, taking such things for granted, the late Alexander Smith waggishly declared that "Tam o' Shanter is the best day's work ever produced in Scotland, since that day THE BRUCE win BANNOCKBURN!". The poet never plumes himself on the rapidity of his powers of composition; but with much force, he says in one of his letters on that subject - "Though the rough material of fine writing is undoubtedly the gift of genius, the workmanship is as certainly the united effort of labout, attention, and pains." It was the 23rd of January 1791, before he announced the completion of this marvellous poem, although we find him, in the November previous, saying to Mrs Dunlop, "I am much flattered by your approbation of my Tam o' Shanter." His words to Alexander Cunningham in January, are these - "I have just finished a poem - Tam o' Shanter." To the same friend he writes on 12th March, 1791. "A thing I have just composed always appears through a double portion of that partial medium in which an author will ever view his own works. I believe, in general, novelty has something in it that inebriates the fancy, and not unfrequently dissipates and fumes away like other intoxication, and leaves the poet patient, as usual, with an aching heart." With something of this same feeling, in sending a copy, apperently of the present poem, to Mr Dalzell, on 19th March, 1791, he says "I have taken the liberty to frank this letter to you, as it encloses an idle poem of mine; and God knows, you perhaps pay dear enough for it if you read it through. Not that is my own opinion; but the author, by the time he has composed and corrected his work, has quite pored away all his powers of critical discrimination."

These quotations in support of the views we are now expressing, certainly would apply with more force to the artistic skill and labourious finish required in the composition of an effective lyric, than the production of a metrical tale like Tam o' Shanter; for we would rather believe all that has been said of the rapidity with which it was composed, than credit by the idle tale that Mary in Heaven was written down by the poet in the presense of his wife, "precisely as it now stands" immediately after having been composed on a frosty harvest midnight in the open field, where he had been found lying on his back gazing at "a star which shone like another moon!"

Professor Wilson argues thus, reasonably, in favour of Tam o' Shanter having been rapidly composed:- "The fact is hardly credible, but we are willing to believe it. Dorset merely corrected his famous 'To all ye ladies now on land' the night before an expected sea-engagement - a proof of his self- possesion; but he had been working at it for days. Dryden dashed off his 'Alexader's Feast' in no time; but the labour of weeks was bestowed on it before it assumed its present state. Tam o' Shanter is superior in force and fire to that Ode. Never did genius go at such a gallop - setting off at score, and making play, but without whip or spur, from starting to winning- post. All is inspiration. His wife with her weans, a little way aside the broom, watched him at work as he was striding up and down the brow of the Scaur, and reciting to himself like one demented - 'Now Tam, O Tam! has thae been queans,' etc. His bonie Jean must have been sorely perplexed; but she was familiar with all his moods, and, like a good wife, left him to his cogitations."

All the world knows that this poem was produced by the author, and presented to Captain Gross, as an inducement to that antiquary to publish some account and give an engraving of Alloway Kirk in his work, called Grose’s Antiquities of Scotland, published at the end of April 1791. The poet also supplied three interesting witch-stories in prose, as traditons concerning Alloway Kirk, and these stories are found to contain the groundwork of the narrative portion of Burns' inimitable poem; but little indeed do they supply of what "the poet has unveiled in penetrating the unsightly and disgusting surfaces of things," as Worsworth finely and phiosophically remarks.

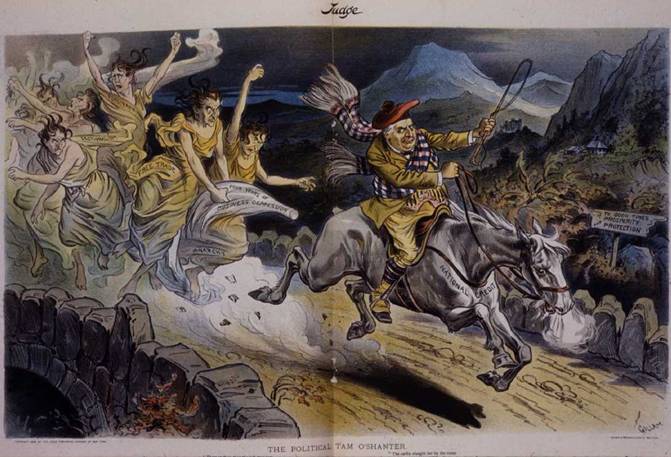

THE POLITICAL TAM O'SHANTER

A political cartoon using the ‘Tam O’Shanter’ tale - 14 November, 1896

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

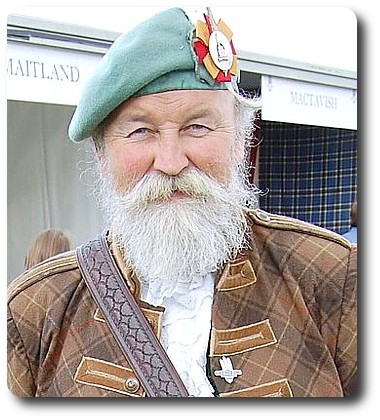

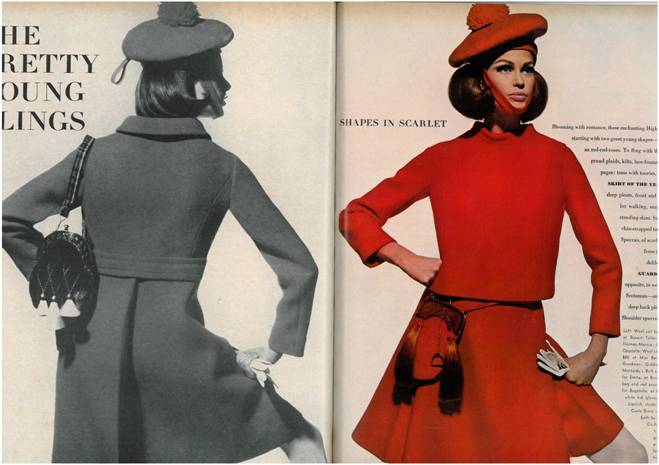

A Tam o' Shanter is also a Scottish-style of hat originally worn by men. However, women have adopted a form of this hat known as a “Tam” or a “Tammy.” The hat is usually made of wool and has a ‘toorie’ (pom-pom) in the centre. It is a floppy type of hat with the crown sometimes twice the diameter of the head. Originally, the hat was made only in blue due to the lack of chemical dyes ("blue bonnets"). The hats are now available in tartan and a wide variety of colors. Tam o' Shanters are a casual alternative to the Balmoral and the Glengarry in Highland dress, and are part of the uniforms of a number of military units.

Tam o'Shanter (TOS) headdress, as worn by the Royal Highland Fusiliers Battalion of the Royal Regiment of Scotland, featuring a unit badge on a tartan backing and surmounted by a feather hackle

A modern Balmoral in black wool, with black grosgrain headband, cockade and ribbons, a red yarn toorie, and a clan crest badge on the cockade

Soldiers of the Scottish Division wearing the Glengarry

A form of Tam o' Shanter called the General Service Cap was worn during World War two by the infantry regiments of the British and Canadian armies instead of berets (which were made standard in the postwar years). They were plain khaki in colour and were stiffer than civilian Tams. Today, the British army’s Scottish Division and some regiments of the Canadian army continue to wear the Tam o' Shanter (abbreviated to TOS) as their "battle headdress"; it has a narrower, flat crown, with Highland battalions shaping theirs sloping down from back to front and the Lowland battalions wearing theirs with the excess material pulled to the right side, similar to a beret. The different battalions of the Royal Regiment of Scotland identify themselves by wearing distinctively coloured hackles on their Tams, and soldiers of The Black Watch of Canada wear a red hackle on both their duty Tams and dress balmorals.

General Sir Neil Ritchie wearing the Tam o' Shanter in France during World War II

Some regiments of the Canadian Army wear different coloured toories: the Royal Highland Fusiliers of Canada have traditionally worn dark green; The North Nova Scotia Highlanders wore red toories during the Second World War; and the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders wore blue. Most regiments wear a khaki toorie, matching the hat. In many regiments it is traditional for soldiers to wear a Tam, while officers (and in some cases senior non-commissioned officers) wear the Glengarry or the Balmoral.

The Tam o' Shanter was traditionally worn by various regiments of the Australian Army which had a Scottish connection. B (Scottish) Company 5th/ 6th Battalion, Royal Victoria Regiment wore both a khaki and blue bonnet at various stages. It appears this has now been superseded by the Glengarry.

Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, Canada traditionally provides every first-year student with a Tam when they first enter the university. Each faculty has its own coloured toorie on the top (red for Arts, gold for Engineering, blue for Medicine, etc.). This tradition reflects the school's strong Scottish origins.

A very large, floppy sort of Tam is often employed as part of academic dress (e.g., in graduation ceremonies), especially in the USA. It is worn by a holder of or candidate for a doctorate degree as an alternative to the mortarboard or Tudor bonnet. In this context, the cap usually has four, six or eight side gores around the head, and may not have a circular crown, but one with angles where the gores meet.

The traditional Irish Aran Tam (short for TAM O'SHANTER) has been around for a long time.

Chinese Tam’s ????

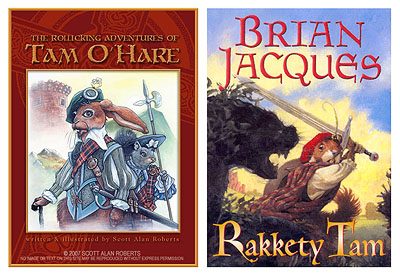

Tam O'Hare is a character created in 1998, complete with a green bonnet, sword (a variation on the circa 1520

Venetian Serenissima Rapier), and a Scottish plaid mantle. The doublet Tam O'Hare is wearing was loosely based

on the doublet worn by Charles I of England. All that to say that Tam O'Hare, while costumed by historical reference,

is quite original. Oh, and his name was inspired by the old Scottish legend, Tam Lyn. and Rabby Burns's, Tam O'Shanter.

Tam O'Hare is an Irish Lord of the 16th century, and the vocal patterns for him are very refined, with a smack of Irish turn-of-phrase. The pirate racoons in the book are written with what has come to be thought of as "pirate slang," such as "...a ship the likes o' ours, what is engaged in the buisness o' piratin'..." or: "Cap'n sez, ye're to stay in yer cabin! And we're here t'make sure ye stays!" Pirate speak. heh.

Tam O'Hare is set in historically recognizable locations in England, Ireland and Scotland.