The Noble Society of Celts, is an hereditary society of persons with Celtic roots and

interests, who are of noble title and gentle birth, and who

have come together in a search for, and celebration of, things Celtic.

"Summer 2011"

‘OLD CAPTAIN NICK’

by

Chevalier William F.K. Marmion

HE IS SAID TO BE THE ‘GHOST OF CARRICKFERGUS CASTLE’, WHOSE APPARITION APPEARS EVERY TIME THERE IS TO BE A WAR – AS A WARNING. BUT NICHOLAS MARMION WAS A REAL PERSON, A SOLDIER, UNTILL HIS OWN DEATH IN 1598

CARRICKFERGUS CASTLE

England’s King Henry VIII started to pursue total control over Ireland by his policy of ‘surrender and re-grant’. He wanted to put all Irish nobles, Gaels and ‘gaelicised’ Norman-Irish, under English law, once and for all. The bait was that ‘Chiefs-of-Name’ would formally renounce their land/ title holdings under Brehon Law*, accept primogeniture** vs. Irish tanistry***, and then receive their lands back along with an English title. Elizabeth I carried on Henry’s policy. It is within that scenario of circa 1560 to 1598 that our man ‘Captain Nick’ lived and soldiered. Con O’Neill in 1542 ‘surrendered’ his title as ‘The O’Neill’ and was re-granted the clan lands solely in his own name and given the new title of ‘Earl of Tyrone’: thus thereafter he was to hold these lands for himself, not in trust for his clan as was historic Irish practice. Later he wished he had left his lands to his second son, Shane, via tanistry, vs. to the government ‘preference’, his oldest son Matthew. Shane was in rebellion, and when his father died (1559) he eliminated Matthew. And became ‘The O’Neill’. And, he continued to attack the English government’s forces wherever he found them. Elizabeth, new to the throne, negotiated with Shane, making peace in 1561 ... to buy time.

* Brehon Law: Prior to English rule, Ireland had its own indigenous system of law dating from ancient Celtic times, which survived until the 17th century when it was finally supplanted by the English common law. This native system of law, known as the ‘Brehon Law’, developed from customs which had been passed on orally from one generation to the next. In the 7th century AD the laws were written down for the first time. Brehon law was administered by Brehons (or brithem). They were the successors to Celtic druids and while similar to judges; their role was closer to that of an arbitrator. Their task was to preserve and interpret the law rather than to expand it. In many respects Brehon law was quite progressive. It recognised divorce and equal rights between the genders and also showed concern for the environment. In criminal law, offences and penalties were defined in great detail. Restitution rather than punishment was prescribed for wrongdoing. Cases of homicide or bodily injury were punishable by means of the eric fine, the exact amount determined by a scale. Capital punishment was not among the range of penalties available to the Brehons. The absence of either a court system or a police force suggests that people had strong respect for the law.

Brehon Law: Prior to English rule, Ireland had its own indigenous system of law dating from ancient Celtic times, which survived until the 17th century when it was finally supplanted by the English common law. This native system of law, known as the ‘Brehon Law’, developed from customs which had been passed on orally from one generation to the next. In the 7th century AD the laws were written down for the first time. Brehon law was administered by Brehons (or brithem). They were the successors to Celtic druids and while similar to judges; their role was closer to that of an arbitrator. Their task was to preserve and interpret the law rather than to expand it. In many respects Brehon law was quite progressive. It recognised divorce and equal rights between the genders and also showed concern for the environment. In criminal law, offences and penalties were defined in great detail. Restitution rather than punishment was prescribed for wrongdoing. Cases of homicide or bodily injury were punishable by means of the eric fine, the exact amount determined by a scale. Capital punishment was not among the range of penalties available to the Brehons. The absence of either a court system or a police force suggests that people had strong respect for the law.

** Primogeniture is the right, by law or custom, of the first-born to inherit the entire estate, to the exclusion of younger siblings. Historically, the term implied male primogeniture, to the exclusion of females. According to the Norman tradition, the first-born son inherited the entirety of a parent's wealth, estate, title or office and then would be responsible for any further passing of the inheritance to his siblings. In the absence of children, inheritance passed to the collateral relatives, in order of seniority of the males of collateral lines.

Primogeniture is the right, by law or custom, of the first-born to inherit the entire estate, to the exclusion of younger siblings. Historically, the term implied male primogeniture, to the exclusion of females. According to the Norman tradition, the first-born son inherited the entirety of a parent's wealth, estate, title or office and then would be responsible for any further passing of the inheritance to his siblings. In the absence of children, inheritance passed to the collateral relatives, in order of seniority of the males of collateral lines.

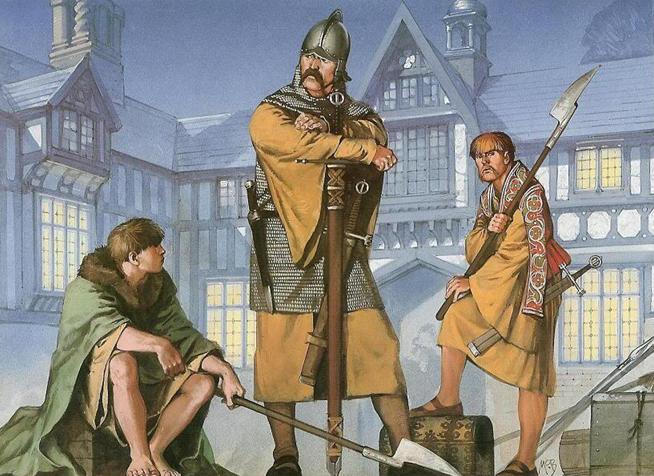

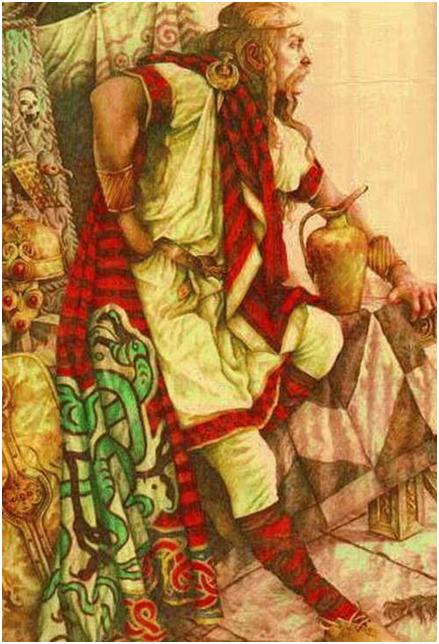

His kern attendants await their Irish lord, Shane O'Neill, during his visit to the court of Elizabeth I, London, 1562. To the English, Ireland was one of the frontiers of Europe, a land on the edge of their world, full of barbarians. It is little surprising then that the courtiers of Elizabethan London observed O'Neill's retainers with 'as much wonder as if they had come from China or America,' according to a contemporary chronicler. Indeed, the Celtic party, headed by The O'Neill, presented a fantastic sight. In defiance of previous Tudor legislation, his warriors were wholly Gaelic in appearance. Their hair was long: fringes hanging down to cover their eyes. They wore shirts with large sleeves dyed with saffron, short tunics and shaggy cloaks. Some walked with bare feet, others wore leather sandals. The galloglas carried battle-axes and wore long coats of mail.

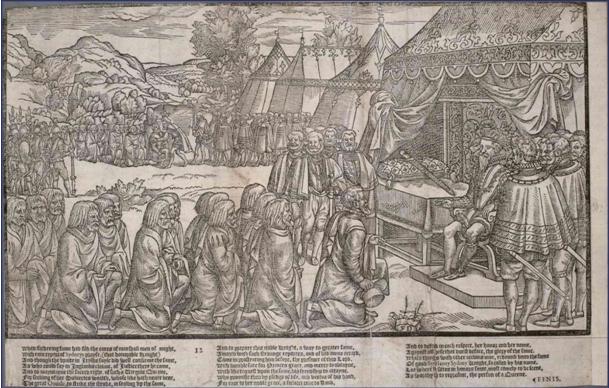

Turlough Lynagh O'Neill and the other Irish kerne kneel to Sir Henry Sidney, Lord-Deputy, in submission 1575 … as part of the ‘surrender and re-grant’ process. In the background Sidney seems to be embracing O'Neill as a noble friend. Note that O'Neill wears a native version of English costume and sports an English haircut, though his entourage still wears distinctive Irish costume.

In Ireland the times continued to be unclear, with conflicting allegiances. Many Gaelic/Norman-Irish chiefs had accepted ‘surrender and re-grant’, MacCarthy Mor becoming Earl of Clancar, Bourke becoming Earl of Clanrickard, to name a few. Most came to realise that the ‘deal’ wasn’t as good as it had looked … and they knew they had violated ancient Irish practice. Many Norman-Irish were reluctant to carry out the English government’s policy but for the most part continued to serve, as the Marmions did, hoping for an eventual peace (that never happened). The Norman-Irish, including the Marmions, were finally thrown totally into the arms of their fellow Irishmen by the time of the 1641 rebellion and the later Cromwellian land confiscations. All, whether O’Neill or O’Brien, Barry, or FitzGerald, were seen simply as ‘Irish Papists’ (Catholics) from that time forward. Shane O’Neill, as per the English government’s deal, had attacked and defeated the MacDonnells of Antrim, in 1565. The Scots* MacDonnells had been a huge bother to the English. Earlier, they and Shane O’Neill had been allies. When later attacked by Hugh O’Donnell, Shane sought refuge with the MacDonnell’s … who welcomed him, entertained him, then killed him. Shane had designated his cousin Turlough Lynagh O’Neill as his tanist, bypassing of course the son of Matthew, Brian, who, as per the English system, inherited the title of ‘Earl of Tyrone’. Turlough indeed became ‘The O’Neill’ under the Irish system, and then had Brian killed … and he would have also killed Hugh O’Neill, the youngest son of Matthew as well, but Hugh was taken safely to London. Turlough eventually submitted in 1575, in a deal allowing him to keep portions of the historic O’Neill lands. The English government agreed because their forces were thin on the ground in the province of Ulster, due to uprisings in other parts of Ireland, e.g. the rebellion in the province of Munster by the FitzGerald Earls of Desmond. This sets the stage for Nicholas Marmion to enter the lists …

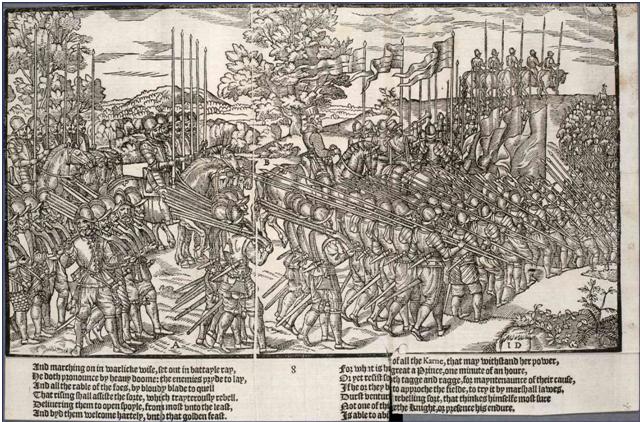

Sidney and the English army on the march with standards and trumpets, pikemen and shot in the foreground, demi-lances behind.

Nicholas, born circa 1540, was of the main branch of the Marmion family, a family which had entered Ireland with ‘Strongbow’ and which had clustered for centuries in and around Carlingford, County Louth. Regardless of sentiment, there was family property in Carlingford etc. to protect from incursions of the O’Neill’s and others. Nicholas chose a soldier’s career with the encouragement of his family; enlisting as a ‘mere Irish’ in 1575, in the company of Captain Wingfield, within the control of Marshal Bagenal, who had been given Newry and Carlingford, and surrounding areas, as an incentive to stop the violence. Nicholas proved adept at his military vocation, for he quickly rose in estimation. By 1580 he was a ‘captain’ of a company – ‘captains’ reporting directly to the Marshal. By 1583-85 he was in the middle of things, as the English government was trying to stop the continuing intra-clan bloodshed and its overflow among the O’Neill’s, which was further complicated by the government beginning to not trust their own candidate, Hugh O’Neill, Baron Dungannon and heir to the Earldom of Tyrone. In anycase, Scottish MacDonnell unrest and infiltration continued, and Captain Nick found himself WITH Hugh O’Neill (and Bagenal and Lord Deputy Perrot and many Gaels) going into Ulster to do battle. Nick was outstanding; he was mentioned in government despatches. He was seconded to Turlough O’Neill ‘in garrison’ during the winter of 1584-85, because of his fluency as an Irish speaker and to ‘watch’ events. Turlough and Marmion became friends, interacting often to the end of Turlough’s life.

The English government knew it couldn’t subdue all O’Neill lands for Hugh O’Neill (and not really wanting to, given the distrust of Hugh), so Elizabeth opted for a new ‘rapproachment’ with Turlough. This was accomplished via a huge parley at Dungannon, and signed on the 10th of August 1585. Hugh was formally installed as ‘Earl of Tyrone’; Turlough retained in peace the historic title of ‘The O’Neill’ and agreed to make common cause against Scottish incursions. This agreement was signed by Bagenal, O’Donnell, Maguire, O’Hanlon, the Lord Deputy, other O’Neill’s ... and by Captain Nicholas Marmion. Nicholas also signed a pact in 1586 with Maguire for the support of his company; he then went off to the province of Connaught, to fight against the Norman-Irish Bourkes/Burkes and their Scots allies. In May 1586, he caught up with the Scots and wounded Alexander, the favourite son of Sorley Boy MacDonnell. Nicholas then chased Alexander to Strabane and finished him off, sending Alexander’s head to the Lord Deputy. This earned the hate of the MacDonnells as well as the further respect of his future enemy, Hugh O’Neill of Tyrone, who was just ‘biding his time’. Nick, in 1587-89, was again sent to the aid of Turlough Lynagh (Bagenal describing him as ‘an ancient, valiant, and well-approved soldier’) to watch Tyrone, and to fight off any attacks by the O’Donnells. Nicholas warned that Hugh did not possess the decency of Turlough, and that he would be a problem. Con O’Neill, a son of Shane, was saying the very same thing, so we see the continued problem of sides shifting! No love was lost between Marmion and Tyrone, but having served together and knowing each others’ qualities, there was obvious respect. O’Neill professed loyalty to the English (again fighting with Marmion against a Maguire uprising in 1593). He then, in early 1595, proclaimed himself as ‘The O’Neill’, and cast off the title of Earl of Tyrone, and went into open rebellion against the English government. Still anxious to protect his own family lands, Captain Nick now found himself in direct opposition to O’Neill.

Hugh O Neill, Earl of Tyrone

Hugh O’Neill was one of the greatest Irishmen, a man who had come to a true understanding of nationhood. Yes, he also had desire for personal power, but faults fade against his ideals. Now he had to fight for his vision. The first major battle between his forces and those of the government (with many Gaelic-Irish fighting on the government side) was at Clontibret, 6 miles from Monaghan, on the 15th of May 1595 ... and O’Neill prevailed. Captain Nicholas, out of ammunition, led a charge against Tyrone’s line with pikes and then sent his Lieutenant, a fellow Carlingford-man named Seagrave, against O’Neill himself ... Seagrave unhorsed O’Neill and was about to give the coup-de-grace when he himself was despatched to the next world, just in the nick-of-time by a son of O’Kane! How Irish history would have changed had Hugh been killed that day! But O’Neill again saw the valour of Nick, and how dangerous he was as an adversary. After this battle, Marmion was once again sent to Turlough, and he fortified Armagh ... he then returned to camp in Newry.

Turlough, a great Gaelic personality himself, along with Sorley Boy MacDonnell, indeed died later in 1595.

In October 1595 there was a parlay between James MacSorley MacDonnell (who had succeeded his father). Nick was present. MacDonnell ‘gave up’ O’Neill (again) and asked for English government help ... but MacDonnell was (again) with O’Neill by July 1596, when the government was back on the defensive. At this time Marmion in garrison at Carrickfergus. As to commitments, many clans Gaelic and Norman-Irish sat on the fence.

The next significant battle was between James MacSorley’s Scots* and the garrison of Carrickfergus, under Sir James Chichester, a poor general, who attacked MacDonnell’s superior force on the 4th of November 1597; having said first to Marmion, ‘your old friends await you’. The battle was a disaster for the English government, with 180 of 250 of their troops killed, including Chichester. Marmion, shot in two places, managed to make it back to Carrickfergus, with reports telling of his bravery in the one-sided battle. When O’Neill heard of the battle and the death of Chichester, etc., he is reported to have said ‘oh, how I would gladly have seen those spared if only we had succeeded in getting the head of Captain Marmion.’ Yes, no tribute like that from a foe. But Tyrone needn’t have worried: Marmion, recovering, was aboard ship from Carrickfergus to Dublin in January 1598, when he fell overboard, and drowned, three miles from Carrickfergus Castle. Foul play? Those were conspiratorial times!

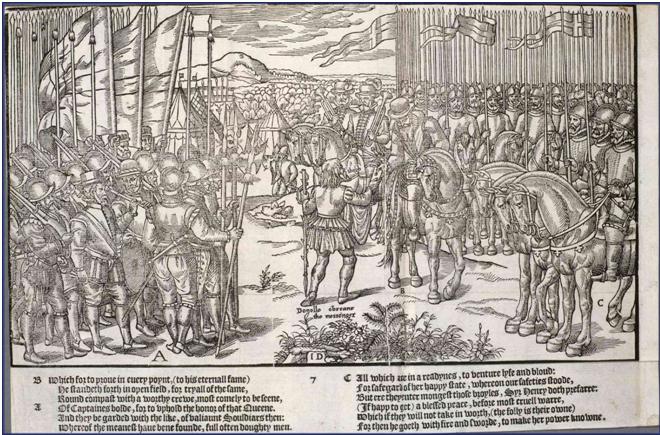

The English army is drawn up for battle, while Sidney himself parleys with a defiant messenger from the Irish.

The years following led to victory then ultimate defeat for Tyrone at Kinsale. The Marmions by 1641 were in full support of the rebellion of Phelim O’Neill. Patrick Marmion, ‘Irish papist’, Captain-of-the-Nation, lost his castle and lands in and around Carlingford in the Cromwellian confiscations, circa 1652. A grandson of Captain Nick, Captain Dominic, indeed was among the ‘Wild Geese’ and served in the regiment of O’Sullivan Mor in Spain.

The legend of Captain Nick as the ghost of Carrickfergus, also called ‘Button Cap’, started immediately, and continues. He was a great soldier, admired by friend and foe alike in those perilous and shifting times. His loyalty to his family and his Catholic faith were all-important to him, and his successors came to see that a new solution was needed to the problem of Ireland. In Norse legend there is a place called ‘Valhalla’, where all the great warriors sit at table after death, however differing in life. Surely Nick, Tyrone, and the MacDonnells share a jar there now.

* ‘Scots” – from the Latin – Scotus = an Irishman (Scoti = Irishmen). In those far off times, the Highlanders and Islanders did not recognise themselves as being a separate race to the ‘Irish’ ... the ‘Scots’ of those days were in fact referred by the English as “wild Irish”. For example consider Clan Donald, who had established themselves on the west coast of modern ‘Scot-land’ and on the north-east coast of Ireland ... as well as in their homeland of the Western Isles. The ‘Scots’ of those times were Gaelic-speaking Roman Catholics, and to a man were the sworn enemies of Lowland Protestants (who were in fact North Britons, not ‘Scots’).

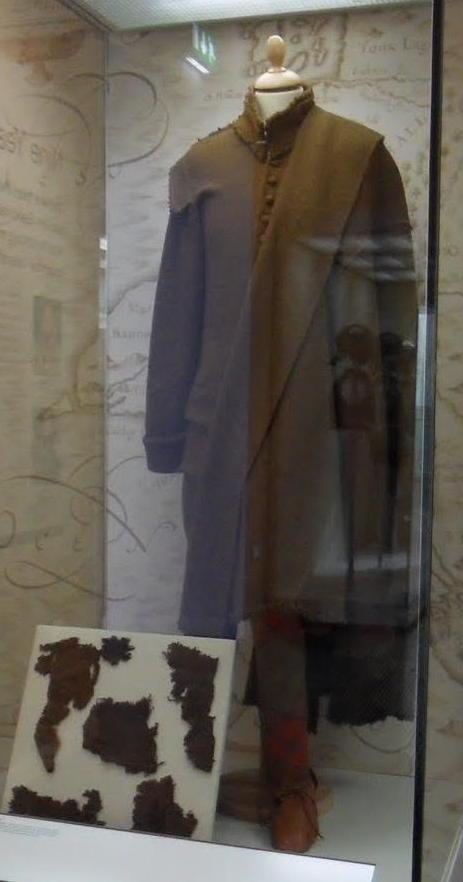

Reconstruction of the Dungiven Costume, a set of clothes discovered in a bog in the 1960s and thought to date to c.1600, the period of Tyrone's rebellion. It was perhaps originally the property of his O'Cahan soldiers. The trousers are of a tartan cloth cut on the bias, while the jacket resembles that of Turlough Luineach O'Neill in Derricke's print. The semi-circular woollen mantle is 8 1/2 feet wide by 4 feet deep. The photos are of the reconstructed Dungiven bog clothing at the Ulster Museum, Belfast.

Hurling

Ireland’s Ancient War Sport

Hurling is a ‘game’ - but not one for the faint-hearted – it’s a team sport played with a small ball and a curved wooden stick. The stick, or hurley (called ‘camán’ in Gaelic) is curved outwards at the end, to provide the striking surface. The ball or ‘sliothar’ is similar in size to a hockey ball but has raised ridges.

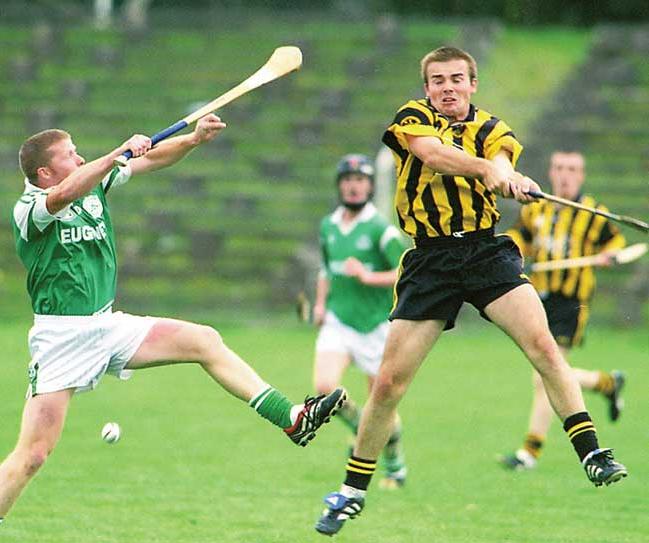

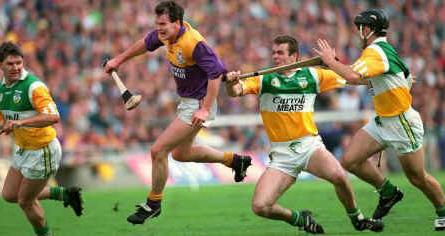

Hurling is played on a field about the same size as a standard soccer pitch. Each team consists of fifteen players, lining out as follows: one goalkeeper, three full-backs, three half-backs, two midfielders, three half-forwards and three full-forwards. Each player is ‘armed’ with a hurley. The object of the game is for players to use the hurley to hit the ball, or slioter, between the opponents’ goalposts - either over the crossbar for one point, or under the crossbar into a net guarded by a goalkeeper for three points. The goalposts are the same shape as on a rugby pitch, with the crossbar lower than a rugby one and slightly higher than a soccer one. You can strike the ball on the ground, or in the air. Unlike hockey, you can pick up the ball with your hurley and carry it for not more than four steps in your hand. After those steps you have to bounce the ball on the hurley and back to your hand, but you are forbidden to catch the ball more than twice. To get around this, one of the skills is running with the ball balanced on the hurley. This is all done with lightning speed, as hurling is one of the fastest sports in the world! Players can handle the ball twice and advance a maximum of four steps before making a pass. Passes can be made either by striking the ball with the hurley or by kicking or slapping it with an open hand for short passes. Players may use their hands only to catch a ball in the air or off a bounce. Side to side shouldering is allowed although ‘body-checking’ (as in ice hockey) or shoulder-charging is illegal (but is known to happen!). No protective padding is worn by players - although a plastic protective helmet with faceguard is recommended, but this is not mandatory for players over 21 years.

Hurling is Europe’s oldest field game. When the Celts came to Ireland as the last ice age was receding, they brought with them a unique culture, their own language, music, script and unique pastimes. One of these pastimes was a game now called hurling.

Hurling was said to be played in ancient times by teams representing neighbouring villages. Villages would play games involving hundreds of players, which would last several hours or even days.

Hurling is older than the recorded history of Ireland. It is thought to predate Christianity, having come to Ireland with the Celts. It has been a distinct Irish pastime for at least 2,000 years. The earliest written references to the sport in Brehon law date from the 5th century AD.

Hurling is related to the game of shinty that is played primarily in Scotland, to cammag on the Isle of Man and to bandy that was played formerly in England and Wales. The tale of the Tain Bo Cuailgne (drawing on earlier legends) describes the hero Cuchulainn playing hurling at Emain Macha. Similar tales are told about Fionn McCumhail and the Fianna, his legendary warrior band.

Recorded historical references to hurling appear in many places, such as in the 13th century Statutes of Kilkenny of the Anglo-Normans which forbade hurling due to excessive violence, stating further that the English settlers of the Pale would be better served to practice archery and fencing in order to repel the attacks of the Gaelic Clans – who were of course, ‘beyond the Pale’. And a 15th century grave slab survives in Inishowen, County Donegal dedicated to the memory of a Gallowglass warrior named Manas Mac Mhoiresdean. This slab displays carvings of a broad-sword, a hurley, and a sliotar. In 1587 Lord Chancellor William Gerrarde complained that English settlers of the Munster Province Plantation were speaking Gaelic and playing hurling. The English also referred to those Irish warriors who were not employed in the service of the English crown, but who followed the Gaelic lords and clan chiefs, as ‘idle swordsmen’ – but these not so ‘idle swordsmen’ played plenty of hurling to stay fit and to maintain their keen eye and quick reflexes for sword-fighting in battles against the English.

The 18th Century is frequently referred to as ‘The Golden Age of Hurling.’ This was when members of the landed gentry in Ireland kept teams of players on their estates and challenged each other’s teams to matches for the amusement of their tenants.

One of the first modern attempts to standardise the game with a formal, written set of rules came with the foundation of the Irish Hurling Union at Trinity College Dublin in 1879. It aimed “to draw up a code of rules for all clubs in the union and to foster that manly and noble game of hurling in this, its native country”.

The founding of the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) in 1884 in Thurles, County Tipperary under the patronage of Thomas Croke, Archbishop of Cashel, and Charles Parnell, turned around a trend of terminal decline by organising the game around a common set of written rules. The 20th century saw greater organisation in Hurling and Gaelic Football. The ‘All-Ireland Hurling Championship’ came into existence along with the provincial championships. Cork, Kilkenny and Tipperary dominated hurling in the 20th century with each of these counties winning more than 20 All-Ireland titles each. Wexford, Waterford, Clare, Limerick, Offaly, Dublin, and Galway were also strong hurling counties during the 20th century.

In current times tens of thousands of fans attend National Hurling League matches and crowds of up to 50,000 at championship matches are not uncommon, which is all quite amazing considering Ireland’s entire population is only a modest 4 million. The revenue generated by this sport and the way it is distributed is even more incredible than the sport itself. There isn’t one professional player in all of Ireland. Hurling, you see, is a sport of pride and not money. All funds are managed by the GAA, an association responsible for supplying players with equipment as well as the building and upkeep of stadiums. Travel expenses for players and coaches are also covered but that is the extent of any incomes. Thanks to hurling regulations which restrict player movement, (players generally represent the town of their birth) the sport has managed to maintain its charm.

Although many hurling clubs exist worldwide, only Ireland has a national team (although it includes only players from weaker counties in order to ensure matches are competitive). The Irish national team and the Scotland’s national shinty team have played for many years with modified ‘international’ match rules. The match is the only such international hurling competition. However, competition at club level has been going on around the world since the late 19th century thanks to emigration from Ireland, and the strength of the game has ebbed and flowed along with emigration trends. Nowadays, growth in hurling is noted in Continental Europe, Australasia, and North America.

References to hurling on the North American continent date from the 1780’s in modern-day Canada concerning immigrants from County Waterford and County Kilkenny, and also, in New York City. After the end of the American Revolution, references to hurling cease in American newspapers until the aftermath of the 1845 – 1852 ‘Irish Holocaust’ (the so-called Potato Famine) when Irish people moved to America in huge numbers, bringing the game with them.

Newspaper reports from the 1850’s refer to occasional matches played in San Francisco, Hoboken, and New York City. The first game of hurling played under GAA rules outside of Ireland was played on Boston Common in June 1886.

In 1888, there was an American tour by fifty Gaelic athletes from Ireland, which was known at the time as the ‘American Invasion.’ This created enough interest among Irish Americans to lay the groundwork for the formation of the North American GAA. By the end of 1889, almost a dozen GAA clubs existed in America, many of them in and around New York City, Philadelphia, and Chicago. Later, clubs were formed in Boston, Cleveland, and many other centres of the Irish American Diaspora.

In 1910, twenty-two hurlers, composed of an equal number from Chicago and New York, conducted a tour of Ireland, where they played against the County teams from Kilkenny, Tipperary, Limerick, Dublin, and Wexford.

Traditionally, hurling was a game played by Irish immigrants and discarded by their children. Many American hurling teams took to raising money to import players directly from Ireland. In recent years, this has changed considerably with the advent of the Internet. Outside of the traditional North American GAA cities of New York, Boston, Chicago, and San Fransico, clubs are springing up in other places where they consist of predominantly American-born players who bring a new dimension to the game and actively seek to promote it as a mainstream sport, especially Joe Maher, a leading expert at the sport in Boston. Currently, the Milwaukee Hurling Club, with 264 members, is the largest North American Hurling club, which is made up of nearly all Americans and very few Irish immigrants.

The GAA have also begun to invest in American college students with university teams springing up in Stanford, Berkley, Purdue, Marquette and other schools. On the 31st of January 2009, the first ever US collegiate hurling match was held between Stanford and UC Berkeley, organized by the newly-formed California Collegiate Gaelic Athletic Association.

The earliest reference to hurling in Australia is related in the book ‘Sketches of Garryowen.’ On the 12th of July 1844 a match took place at Batman’s Hill in Melbourne as a counterpoint to a march by the Orange Lodge. Reportedly, the hurling match attracted a crowd of five hundred Irish immigrants, while the Orange Lodge march shivered out of existence in the cold southern winter.

In 1885, a game between two Sydney based teams took place before a crowd of over ten thousand spectators. Reportedly, the contest was greatly enjoyed despite the fact that one newspaper dubbed the game “two degrees safer than war.”

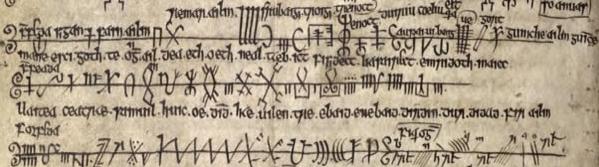

Ogham: Ancient Alphabet of the Celts

By Douglas S. Files, MD, MPH, NSC

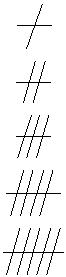

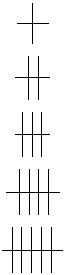

Ogham was an alphabet used in the early medieval period (4th to 10th centuries A.D.) to write Old Irish and sometimes Brythonic. Approximately 500 Ogham inscriptions can be found on rocks in Ireland and western Britain. They were deciphered because some are bilingual with Latin next to the Ogham. The etymology of the word “Ogham” is unclear. Some sources state it came from the Irish og-uaim (point seam, i.e. the point made by a sharp weapon). Others postulate that it arose from the name of the Irish god Ogma.

Three main theories exist for the creation of Ogham. Some scholars expect it was originally designed as a cipher or code so that only Celts could understand it - and Roman Britons could not. The second idea is that early Christian communities had difficulty transcribing Celtic into the Latin alphabet so they devised a system of their own. The third theory states that it evolved from a system of hand signals used by Gaulish druids. This seemed reasonable, given the organization of the alphabet into 5-letter groups like 5 fingers on a hand. The latter theory has lost ground in recent years due to studies of the letters showing that they were specifically created for the sounds of the Celtic language.

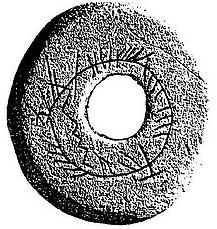

The 8th century Buckquoy spindle-whorl, reading "a blessing on the soul of L."

Strictly speaking, Ogham refers only to the form of the letters. It is neither a language nor the letters themselves, which are called Beith-luis-nin after the names of the first letters. (This is analogous to our word alphabet which derives from alpha and beta, the first two Greek letters.)

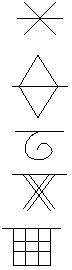

The Ogham alphabet originally contained 20 characters, arranged into four “families” of five letters called aicmi. Each aicme was named for its first letter. Later 5 other characters were introduced.

Aicme Beith

B Beith, Beithe

Beith, Beithe

Birch

Birch

L Luis

Luis

Rowan

Rowan

F, V Fearn, Fern

Fearn, Fern Alder

Alder

S Saille, Saile, Suil

Saille, Saile, Suil Willow

Willow

N Nion, Nuin, Nin

Nion, Nuin, Nin Ash

Ash

Aicme Huath

H

Huath, Huathe, Uath

Huath, Huathe, Uath

Hawthorn

Hawthorn

D

Duir, Dair, Daur

Duir, Dair, Daur

Oak

Oak

T

Tinne, Teine

Tinne, Teine

Holly

Holly

C, K Coll, Call

Coll, Call

Hazel

Hazel

Q, CC Quert, Queirt, Ceirt, Cert

Quert, Queirt, Ceirt, Cert Apple

Apple

Aicme Muin

M Muin

Muin Vine/Bramble

Vine/Bramble

G Gort

Gort Ivy

Ivy

Ng Ngetal, nGétal, Ngeadal

Ngetal, nGétal, Ngeadal Reed

Reed

St Straif, Straiph Blackthorn

Z Straith

Straith Blackthorn

Blackthorn

R Ruis

Ruis Elder

Elder

Aicme Ailm

A Ailm, Ailim

Ailm, Ailim Fir, Elm, Pine

Fir, Elm, Pine

O Onn, Ohn

Onn, Ohn Gorse (Furze)

Gorse (Furze)

U, W Ur, Ura

Ur, Ura Heather

Heather

E Eadhadh, Eadha, Edad

Eadhadh, Eadha, Edad Aspen

Aspen

I, J, Y Iodho, Iodhadh, Ido, Idad

Iodho, Iodhadh, Ido, Idad Yew

Yew

The Forfeda

EA CH, K Éabhadh, Ebad

Éabhadh, Ebad  Honeysuckle, Aspen

Honeysuckle, Aspen

OI, TH Oir, Or

Oir, Or Spindle Tree, Ivy

Spindle Tree, Ivy

UI, PE  Uilleann, Uileand, Uilen

Uilleann, Uileand, Uilen Beech, Honeysuckle

Beech, Honeysuckle

IO, PH Ifin, Iphin

Ifin, Iphin Gooseberry, Beech

Gooseberry, Beech

AE,

X, XI Amhancholl, Eamhancholl,

Amhancholl, Eamhancholl,  Witch Hazel, Pine

Witch Hazel, Pine

No letter for the “p” sound existed in the original Ogham since that sound was lost in Proto-Celtic. But when Latin loan words seeped into Celtic (for example, in the name Patrick) it was necessary to have one. The names of the Ogham letters mostly derive from tree or plant names. Thus we see letters called beith (birch), fearn (alder), saille (willow) and duir (oak). Other letters are named for ash, ivy, herb, holly, fern and blackthorn.

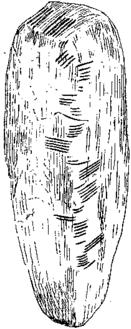

While all remaining Ogham inscriptions are on stone, it was probably extensively used on trees and sticks as well. Some of the remaining stones are monuments (grave stones), such as the one below that reads: Bivaidonas maqi mucoi cunavali “Of Bivaidonas, son of the tribe Cunavali”. Others mark land boundaries. When inscribed on stones, Ogham is written vertically from bottom to top.

It should also be mentioned that the Ogham alphabet held magical power for the Celts. This is not all that surprising, as all writing seems mystical to those who cannot read it. (How do you feel about a Mandarin Chinese text?) The Celts said that Ogham held druidic secrets which could be used in magical spells. Divination sticks were engraved with Ogham letters, and modern druids still do this. In fact the word druid probably derived from duirwydd (oak-seer).

Sample text in Ogham

LIE LUGNAEDON MACCI MENUEH “The stone of Lugnaedon son of Limenueh”

From: Inchagoill Island, County Galway, Ireland

BOOK REVIEW

The Rollicking Adventures of Tam O'Hare

An entertaining, adventurous story that lends itself to historical, educational, and spiritual lessons (without being pretentious or "religious"). The story expresses the author's belief that Honor is the only true gift one can give oneself. The book was initially written for elementary school children, but it has garnered a following with high school and college-aged students … and, dare I say it, older gentlemen !!!

Product Details

Synopsis

Tam O'Hare, Irish Lord and swashbuckling adventurer, along with his young squire, Horatio MacNutt, set out to find a young girl who's been stolen by the faeries -- the "Good People" of Irish and Scottish lore.

Filled with swashbuckling action, pirates, and high seas battles, this fanciful tale is set against the historic backdrop of 16th-century Ireland, Scotland, and England, where the English are foxes, wolves, and hawks, and the Irish and Scots are rabbits, squirrels, badgers, and bears.

*** Tanistry was a Gaelic system for passing on titles and lands. In this system the Tanist (Irish: Tànaiste) was the office of heir-apparent, or second-in-command, among the royal Gaelic dynasties of Ireland, Scot-land, and the Isle of Man, to succeed to the chieftainship or to the kingship. The Tanist was chosen from among the heads of the roydammna or "righdamhna" (literally, those of kingly material) or, alternatively, among all males of the sept, and elected by them in full assembly. The eligibility was based on ‘patrilineal’ relationship, which meant the electing body and the eligibles were ‘agnates’ with each other. (Patrilineality, or agnatic kinship, is a system in which one belongs to one's father's lineage.) The composition and the governance of the Irish clans were built upon male-line descent from a similar ancestor. The office of Tanist was noted from the beginning of recorded history in Ireland, and probably pre-dates it. A story about Cormac mac Airt (an ancient High King of Ireland) refers to his eldest son as his Tanist. (Using their system of Tanistry, the native Irish chose their best and most able future leaders from the extended family of the King or Chief, unlike the English tradition of ‘primogeniture’ where, even though the eldest son may have been hopelessly inept, he would still become head of the extended family and their followers.)

Tanistry was a Gaelic system for passing on titles and lands. In this system the Tanist (Irish: Tànaiste) was the office of heir-apparent, or second-in-command, among the royal Gaelic dynasties of Ireland, Scot-land, and the Isle of Man, to succeed to the chieftainship or to the kingship. The Tanist was chosen from among the heads of the roydammna or "righdamhna" (literally, those of kingly material) or, alternatively, among all males of the sept, and elected by them in full assembly. The eligibility was based on ‘patrilineal’ relationship, which meant the electing body and the eligibles were ‘agnates’ with each other. (Patrilineality, or agnatic kinship, is a system in which one belongs to one's father's lineage.) The composition and the governance of the Irish clans were built upon male-line descent from a similar ancestor. The office of Tanist was noted from the beginning of recorded history in Ireland, and probably pre-dates it. A story about Cormac mac Airt (an ancient High King of Ireland) refers to his eldest son as his Tanist. (Using their system of Tanistry, the native Irish chose their best and most able future leaders from the extended family of the King or Chief, unlike the English tradition of ‘primogeniture’ where, even though the eldest son may have been hopelessly inept, he would still become head of the extended family and their followers.)

Following his murder by a member of the ‘Deisi’ (various different peoples listed under the heading déis shared the same status in Gaelic Ireland, and had little or no actual kinship, though they were often thought of as genetically related), another roydammna, Eochaid Gonnat, succeeded as king (he ruled for a year, before falling in battle). The Gaels exported tanistry and other customs, to those parts of Scotland which they controlled after 400 AD. In Ireland, the tanistry continued among the dominant dynasties, as well as lesser lords and chieftains, until the mid-16th century. In a much reduced form, it lingered until as late as the 1840s. When in 1943 the government of Ireland appointed its first new Chief Herald, it did not reintroduce tanistry. It is now hard to fathom why, but the ‘modern’ Irish state, via the Office of the Chief Herald of Ireland, granted courtesy recognition to Irish chiefs based on the English custom/ law of ‘primogeniture’ from the last known chief.

Cormac Mac Airt (A.D. 227-268)